![]()

Chapter 1

A is for Abacus

Computing machinery dates back to the earliest times in history. Devices helped people solve complicated problems, with a strong focus on astronomy. Later, as arithmetic became more involved and abstracted, the algorithms for computing changed direction, and the devices became associated more with numerical calculations. Calculations became more complex, and computing became a specialized occupation.

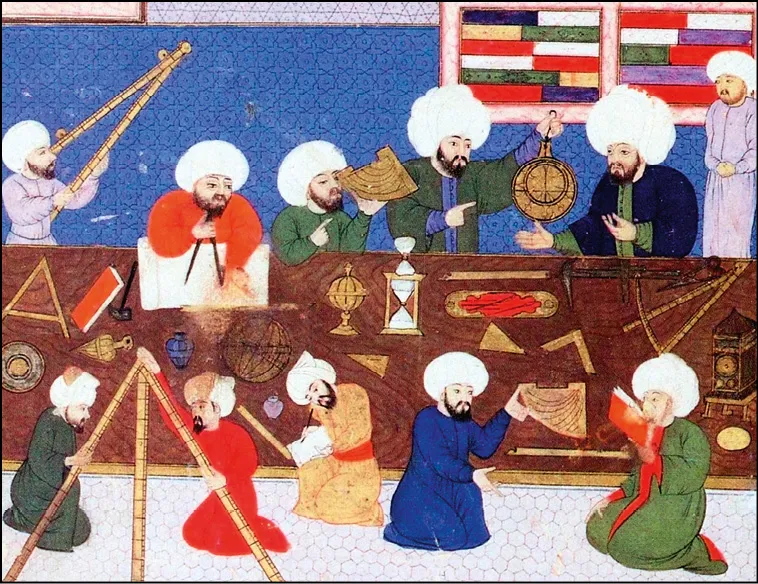

Astronomy provided the earliest catalyst for creating computing machines. Here, Ottoman scholars use a variety of instruments in the Istanbul Observatory.

A is for abacus. Or maybe for astrolabe, or for the Antikythera mechanism, or for any number of antiquated devices used for computing. Humans have been designing problem-solving machines since the earliest days of civilization. In a sense, all machines are built to solve problems, such as raising water from deep underground or lifting heavy loads. Eventually, the specifically intellectual problems of arithmetic, measurement and astronomical prediction also proved amenable to mechanical help.

So what distinguishes these devices from other remarkable ancient artefacts? What about dividers, plumblines, set-squares and so forth? These are all clever machines that assist people with practical problems in navigation, surveying and engineering by helping with the creation and checking of data. But they lack one central feature: none of these devices is able to give its user the answer to a problem. That is because these objects are not involved in the process of computing.

Astronomical answers

The Assyrians may not have been the first to develop serious computing techniques, but thanks to their habit of preserving their works on clay tablets, much of their thinking – in particular, their thinking about mathematics – has survived. Their ability to manipulate highly complex numerical problems – including fractions, square roots, quadratic equations, and more – implies a great deal of sophistication in their society. Their work extended to the measurement and division of the day and of the circle, concepts that have been in continuous use ever since.

Religion has often been closely connected with astronomy. It was self-evident that the sun moved around the earth once a day (or appeared to, anyway), but the behaviour of other heavenly bodies was more complicated. Although the moon waxes and wanes every four weeks and affects the tides and the level of coastal waters in predictable ways, working out where and when it will appear in the sky is more difficult. And then there are eclipses. These have often been seen as troublesome events, the harbingers of disaster, and need to be predicted in order to prepare appropriate propitiations. The minor stars and planets are even more complex. To keep on top of this required years of study. Prediction, in a pre-algebra era, needed machinery.

This Star Chart from Sumeria, dated c.3300bc, was used for astrological calculations.

Devices to assist with astronomical computing were developed in many continents and in many cultures. The Mayans compiled data and calculations related to astronomy as long ago as the 9th century bc, using a catalogue of such information to make predictions about eclipses, the phases of the moon and the movements of the planets. The ancient Greeks and Chinese each invented forms of ‘armillary sphere’ to demonstrate the motion of stars about the earth.

At the end of the 10th century ad, the Persian astronomer Abu Mahmud Hamid ibn al-Khidr Al-Khujandi constructed a huge sextant-like device near Tehran to measure the earth’s tilt. In Samarkand, in the early 15th century, Jamshid al-Kashi developed machinery to predict the alignment of planets. The list could go on, but perhaps the most famous is the complex Antikythera mechanism, which has been called the world’s oldest computer.

At the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford there is an astonishing collection of ‘astrolabes’. Astrolabes are used to determine the angle of elevation of stars. The elevation of a particular astronomical body varies with latitude and so the device could help travellers identify their location. The earliest astrolabe in the Oxford collection dates from around ad900 and was made in Syria or Egypt. As Islamic culture percolated into Europe via southern Spain, along with it came Islamic knowledge, equipment and computation. One of the earliest astrolabes in the Oxford collection dates from around ad1300, with star pointers in the form of birds with long beaks. Astrolabes of increasing decorative quality and sophistication began to be created in Europe around the time of the Renaissance, though their accuracy for navigation at sea was poor when compared with other instruments such as a sextant. For people of Islamic faith, the direction of Mecca is a necessary calculation; an astrolabe can be used for that purpose. Astrolabes are probably better classified as aids to measurement rather than computational devices, but the contrary argument can be made since (like the Antikythera mechanism) they provide short-cuts for the user, with much information and the product of accumulated knowledge stored within their dials and scales.

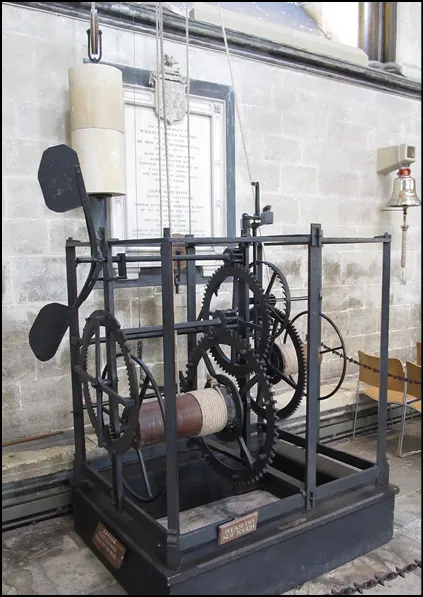

Another astronomical device that falls between measurement and computation is the clock. We may not ordinarily think of a clock as a means to observe the behaviour of the heavens but, as the Assyrians taught us, the division of a day into equal parts is a natural progression from an observation of the sun’s movement. Telling the time using an instrument such as a sundial or a water-clock is unlikely to be regarded as an exercise in computing. But when you consider the complexity of a modern mechanical clock with an escapement, spring- or weight-driven motion and gearing to convert motion to a read-out on the clock’s face, the distinction becomes fuzzy. The machine is actually computing the time, rather than relying on the passage of time to give you an observation: were it not so, clocks would not run fast or slow. The earliest mechanical clocks that compute, rather than measure, time, were invented in China in the 8th century ad. In Europe, clocks with escapements were put into many ecclesiastical buildings at the end of the 13th century ad, particularly in England, France and Italy.

Clocks compute, rather than simply measure time. Innovation began in the churches, as can be seen in this clock from Salisbury Cathedral, which features an escapement.

It was not always the case that hours were of equal duration. Clock technology had to reflect this. Traditional Japanese time-keeping required the hours of daylight to be divided into six parts and the hours of darkness also to be so divided. As summer recedes into winter the durations of these parts will change. Western engineering during the Japanese Edo period (1603–1868ad) had allowed clocks of immense beauty and accuracy to be developed for timekeeping of equal-length hours; the challenge to the engineers’ ingenuity was to find a mechanism to handle the inequality of Japanese hours.

Pillar clocks do not have a Western-style circular face but a descending weight that passes markers as the day wears on. The markers can be adjusted according to the season or whether it is day or night. When the clock is wound, the weight is brought back to the start of its path.

Other types of Japanese clock do have a circular face. A curious example in the Seiko Museum in Tokyo has a rotating face, but fixed hands. Every day, at dawn and again at dusk, the weights that drive the mechanism that rotates the face must be adjusted slightly to ensure the time-keeping keeps pace with the changing seasons. Once Japanese culture was exposed to Western ideas – approximately at the same time as the Renaissance in Europe – this brought with it the notion of fixed-duration hours and mechanical European-style clocks. Soon after Japan ended its policy of isolation in 1873, the traditional Japanese method of time-keeping disappeared.

Assyrian angle

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were justly ranked among the s...