- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The ramifications of the Manhattan Project are still with us to this day. The atomic bombs that came out of it brought an end to the war in the Pacific, but at a heavy loss of life in Japan and the opening of a Pandora's box that has tested international relations.This book traces the history of the Manhattan Project, from the first glimmerings of the possibility of such a catastrophic weapon to the aftermath of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It profiles the architects of the bomb and how they tried to reconcile their personal feelings with their ambition as scientists. It looks at the role of the politicians and it includes first-hand accounts of those who experienced the effects of the bombings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Manhattan Project by Al Cimino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Einstein Letter

On 2 August 1939, Albert Einstein, the world’s most famous scientist – the Nobel laureate who had stood the world of physics on its head with his theories of relativity – sent a letter to the President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It said:

Sir:

Some recent work by E. Fermi and L. Szilard, which has been communicated to me in manuscript, leads me to expect that the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future. Certain aspects of the situation which has arisen seem to call for watchfulness and if necessary, quick action on the part of the Administration. I believe therefore that it is my duty to bring to your attention the following facts and recommendations.

In the course of the last four months it has been made probable through the work of Joliot in France as well as Fermi and Szilard in America that it may be possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium, by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated. Now it appears almost certain that this could be achieved in the immediate future.

This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable – though much less certain – that extremely powerful bombs of this type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory. However, such bombs might very well prove too heavy for transportation by air.

The United States has only very poor ores of uranium in moderate quantities. There is some good ore in Canada and former Czechoslovakia, while the most important source of uranium is in the Belgian Congo.

In view of this situation you may think it desirable to have some permanent contact maintained between the Administration and the group of physicists working on chain reactions in America. One possible way of achieving this might be for you to entrust the task with a person who has your confidence and who could perhaps serve in an unofficial capacity. His task might comprise the following:

a) to approach Government Departments, keep them informed of the further development, and put forward recommendations for Government action, giving particular attention to the problem of securing a supply of uranium ore for the United States.

b) to speed up the experimental work, which is at present being carried on within the limits of the budgets of university laboratories, by providing funds, if such funds be required, through his contacts with private persons who are willing to make contributions for this cause, and perhaps also by obtaining co-operation of industrial laboratories which have necessary equipment.

I understand that Germany has actually stopped the sale of uranium from the Czechoslovakian mines which she has taken over. That she should have taken such early action might perhaps be understood on the ground that the son of the German Under-Secretary of State, von Weizsacker, is attached to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, where some of the American work on uranium is now being repeated.

Yours very truly,

Albert Einstein

The first page of Albert Einstein’s original letter of 2 August 1939 to President Roosevelt about the use of uranium to produce a nuclear bomb and potential sources of the ore.

The letter was to be delivered by Alexander Sachs, a Wall Street economist and unofficial advisor to the president, along with a memorandum prepared by Hungarian émigré physicist Leo Szilard, the man who had first conceived of the possibility of making an atomic bomb six years earlier and the author of the letter Einstein had signed.

Although he was a longtime friend, even Sachs had trouble getting in to see Roosevelt, who was busy dealing with the situation in Europe. On 23 August, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact. European armies began to mobilize and on 1 September Hitler invaded Poland, precipitating World War II.

It was not until 11 October that Sachs got in to see the president. Sachs had read Einstein’s letter and Szilard’s memorandum, and explained that recent research on chain reactions utilizing uranium made it probable that large amounts of power could be produced – enough to make extremely powerful bombs. The German government was actively supporting research in this area and it would be sensible if the US government did the same. Initially Roosevelt was noncommittal and worried about finding the money for such research, but at a second meeting over breakfast the next morning he became convinced of the value of exploring atomic energy.

Leo Szilard was one of a number of European scientists who had fled to the United States in the 1930s to escape the Nazis. He and fellow Hungarian refugees Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner regarded it as their duty to alert Americans to the possibility that German scientists might win the race to build an atomic bomb. If they did, it was clear that Hitler would be more than willing to use such a weapon.

Roosevelt wrote back to Einstein on 19 October 1939, telling him that he had set up a committee consisting of Sachs and representatives from the Army and Navy to study the use of uranium. He believed that the US could not take the risk of allowing Hitler to achieve unilateral possession of an atomic bomb.

Szilard, Teller, Wigner and Italian physicist Enrico Fermi would all be involved in the project. The British were also working on building an atomic bomb, but they did not have the resources to pursue a full-fledged research programme while fighting for their survival. Nor were their facilities safe from airborne attack. Consequently, the British acceded, albeit reluctantly, to US leadership and sent their scientists to the States.

Despite Allied fears, the Germans put their scientific energies into areas such as jet fighters and rockets – the V1 and V2. By the end of the war, they would be scarcely nearer to producing atomic weapons than they had been at the beginning. However, the Americans and the émigré scientists were not to know that.

Elsewhere, work in France under Frédéric Joliot at the Radium Institute in Paris was halted during the German occupation. Joliot had smuggled his notes and materials to England, and joined the Resistance.

The Russian atomic research programme grew increasingly active as the war drew on. But, again, there were other priorities and the first successful Soviet test was not conducted until 1949. The Japanese managed to build several cyclotrons by the war’s end. These were key in the development of the atomic bomb, but the research effort could not be maintained in the face of increasing scarcities.

Only the US, as a late entrant into World War II, protected by oceans on both sides and with its vast industrial resources, managed to take the theories of a handful of young physicists from the laboratory to the battlefield in what became known as the Manhattan Project – and, as a result, change the nature of warfare and the world forever.

Chapter Two

Splitting the Atom

At the beginning of the 20th century, New Zealander Ernest Rutherford became interested in the radiation given off by radioactive materials. It came in three types: alpha, beta and gamma. It was alpha radiation that particularly interested him because it comprised particles of the tangible mass. These had a positive charge and, in 1907, he proved they were helium ions – that is, atoms of helium stripped of their electrons. At the time, atoms were thought to be solid objects with lightweight electrons embedded in a mass of positively charged material, like raisins in a pudding. This was known as the ‘plum pudding’ model.

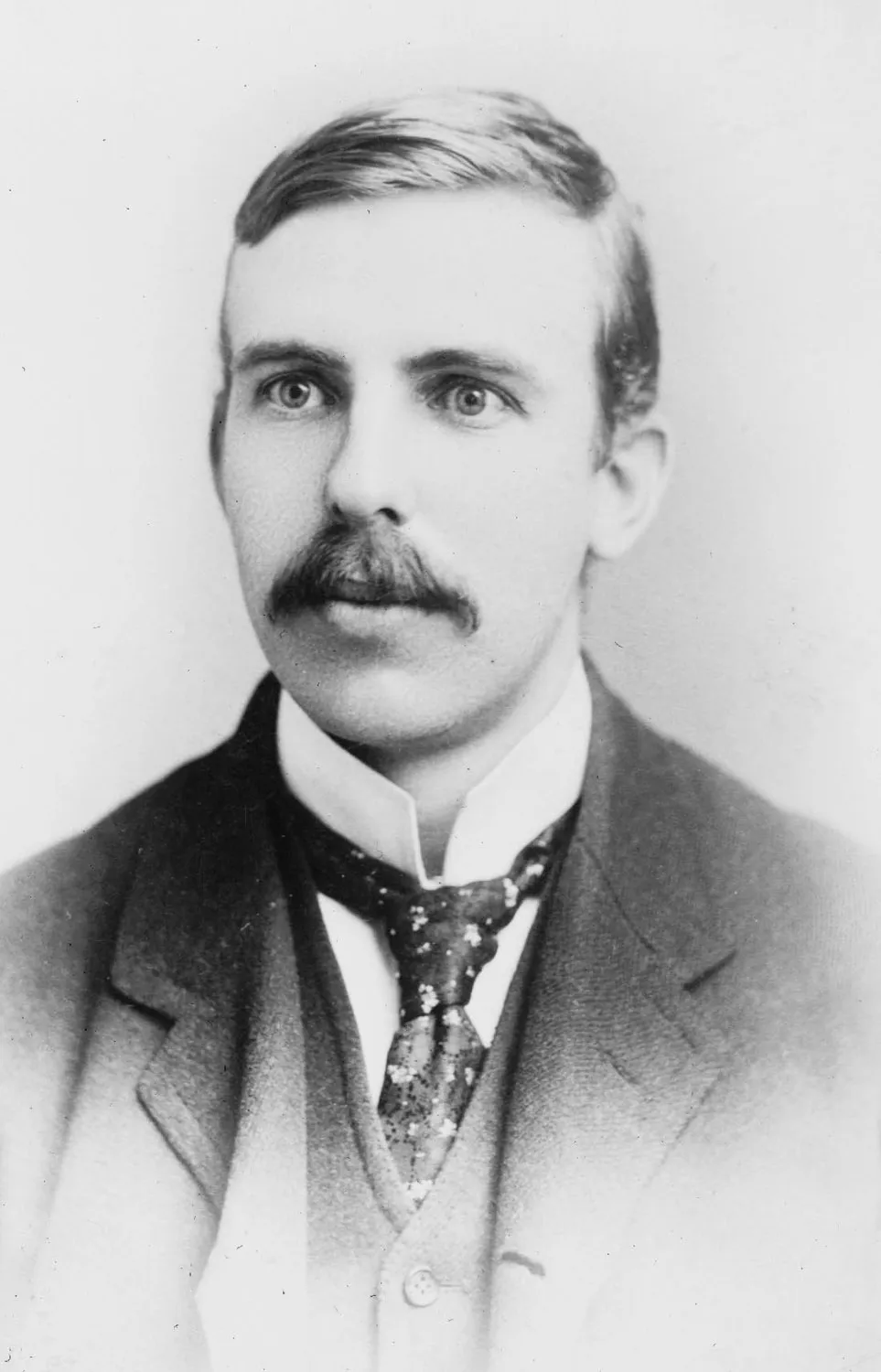

The New Zealand-born chemist Ernest Rutherford (1871–1937).

At Manchester University, Rutherford – a chemist, although he became the father of nuclear physics – began firing alpha particles at a thin sheet of gold. These energetic particles should have passed straight through. However, some bounced back.

‘It was almost as incredible as if you fired a fifteen-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you,’ he said.

This meant that the atom could not be a uniform solid. Rather, it must be largely empty space with most of its mass concentrated in a tiny central nucleus, Rutherford realized in 1911. It was a mini-solar system. Two years later, Danish physicist Niels Bohr explained that while the chemical properties of the atom are due to the orbiting electrons, radioactivity lies in the nucleus.

In 1919, Rutherford discovered that by bombarding nitrogen with alpha particles you could change it into oxygen. This was the first artificial transmutation of an element, a process not thought possible outside alchemy. The process gave off positively charged particles, which he identified as the nuclei of hydrogen atoms, later called protons.

Returning to Cambridge as head of the Cavendish Laboratory, Rutherford continued to bombard various elements with alpha particles. With light elements he could produce similar transmutations, but with heavier elements the alpha particles were repelled by the higher positive charge on the nucleus. To investigate the nuclei of heavier elements, more energy was needed and particle accelerators were developed.

In 1932, James Chadwick, who Rutherford had brought to the Cavendish from Manchester, identified a third particle, the neutron, so named because it had no charge. This had been predicted by Rutherford and completed the picture of the atomic structure as we now know it.

The number of protons in the nucleus determined the element’s atomic number. Hydrogen, with one proton, came first on the periodic table of elements and uranium, with 92 protons, came last. This simple scheme had become more complicated when chemists discovered that many elements existed at different atomic weights even while displaying identical chemical properties. Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron explained this mystery. Atoms of the same element had different weights because they contained different numbers of neutrons. These differing atoms of the same element were called isotopes.

The three isotopes of uranium, for example, all have 92 protons in their nuclei and 92 electrons in orbit around them. But uranium-238, which comprises over 99 per cent of natural uranium, has 146 neutrons in its nucleus, compared with 143 neutrons in the rare uranium-235 (comprising 0.7 per cent of natural uranium) and 142 neutrons in uranium-234 (0.006 per cent). The slight difference in atomic weight between the uranium-235 and uranium-238 isotopes was an important factor in the making of the atomic bomb.

The year 1932 produced other notable events in atomic physics. Two of Rutherford’s students, the Englishman John D. Cockroft and the Irishman Ernest T. S. Walton, were the first to split the atom when they bombarded lithium with protons generated by a particle accelerator, causing the nucleus to split into two helium nuclei. That year, Ernest O. Lawrence and his colleagues M. Stanley Livingston and Milton White on the Berkeley campus of the University of California successfully operated the first cyclotron. This produced the high-energy particle beams needed for further nuclear research.

M. Stanley Livingston (L) and Ernest O. Lawrence in front of the 27-inch cyclotron at the old Radiation Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

Moonshine

Lawrence’s cyclotron, the Cockroft-Walton machine and the Van de Graaff electrostatic generator, developed by Robert J. Van de Graaff at Princeton University, were types of particle accelerators designed to bombard the nuclei of various elements to disintegrate atoms. These early accelerators produced beams of either alpha particles or protons. Since alpha particles and protons are positively charged, they met substantial resistance from the positively charged target nucleus. Even high-speed protons and alpha particles scored a direct hit on a nucleus in only about one in a million times. Most simply passed by the target nucleus or were deflected.

Bombarding atoms this way was a useful method of furthering knowledge of nuclear physics. During such collisions, a small amount of matter would be lost, resulting in the release of huge amounts of energy given by Einstein’s famous formula E= mc2. This showed the equivalence of mass and energy, where E is the energy, m is the mass and c is the speed of light, around 300,000 kilometres a second, or some 670 million an hour. So c2 is a very large number indeed.

But to Rutherford, Einstein and Bohr it was unlikely to harness the power of the atom for practical purposes any time in the near future. In a speech in 1933 – the year Hitler came to power in Germany – Rutherford called such expectations ‘moonshine’. Einstein compared particle bombardment with shooting in the dark at scarce birds, while Bohr agreed that the chances of taming atomic energy were remote. The followi...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The Einstein Letter

- Chapter Two: Splitting the Atom

- Chapter Three: Science Goes to War

- Chapter Four: The Military Move In

- Chapter Five: The Biggest Secret

- Chapter Six: Plutonium Piles

- Chapter Seven: Los Alamos

- Chapter Eight: Deadline

- Chapter Nine: Trinity

- Chapter Ten: The Potsdam Declaration

- Chapter Eleven: The Quick and the Dead

- Chapter Twelve: The Public Domain

- Picture Credits

- Copyright