![]()

Chapter 1

What can we learn from a brain?

We can’t watch the brain working like we can watch a heart pumping.

Psychology is the study of what goes on in the brain – thinking, learning, personality, dreams, desires, character formation, behaviour determination, and disorders of all of those. But unlike the study of what goes on in, say, the heart, there is no mechanical process to observe directly. So scientists have had to find some ingenious ways of monitoring our thought processes.

Viewing our thoughts

In the early days of psychology, the only way of looking at a brain directly was once its owner had died. All psychological study had to be by experimenting with, observing and questioning live brain-users. While all those techniques remain extremely useful today, we now have ways of viewing the living brain while it’s doing its stuff. But viewing the brain raises as many questions as it answers. Knowing about the biology of the brain only takes us so far. We can see that it is doing something, but we still can’t see quite what it is doing, or how. We can see neurons firing as someone thinks, but can’t see what they are thinking, or why they had that thought, or how they will remember (or forget) it.

NEUROSCIENCE – THE BASICS

The brain is made up of lots of cells called neurons (nerve cells), which are responsible for producing neural activity. ‘Lots’ is around 86 billion. Neural activity includes receiving ‘messages’ from the receptors in the sensory organs located in different parts of the body and transmitting messages to activate the muscles, for example, in other parts of the body. Some actions are conscious, such as raising your arm; some are unconscious, such as increasing heart beat.

Different parts of the brain are responsible for different types of neural activity. Information from the eyes is transmitted to the visual cortex at the back of the brain and processed to produce the images we ‘see’ in the mind. Emotions, on the other hand, are processed in the amygdalae, two small structures located deep within the brain.

Size matters

| ANIMAL | NEURONS |

| Fruit fly | 100,000 |

| Mouse | 75,000,000 |

| Baboon | 14,000,000,000 |

| Cockroach | 1,000,000 |

| Cat | 1,000,000,000 |

| Human | 86,000,000,000 |

What goes where?

For millennia, the only way to discover which parts of the brain were used for different functions was to observe people who had suffered head injury and note how that had affected their mental or physical abilities, mood or behaviour. The changes resulting from the head injury were a good indication that different parts of the brain were responsible for different functions (emotions, cognition, personality and so on). Post-mortem examination revealed brain damage that might be related to changes or impaired function noticed in the person when they were alive. To acquire meaningful insights into the workings of the brain, scientists needed lots of brains to examine and sophisticated scientific equipment to do it with. So the brain was pretty much a closed book until the 20th century. It’s not a very open book even now.

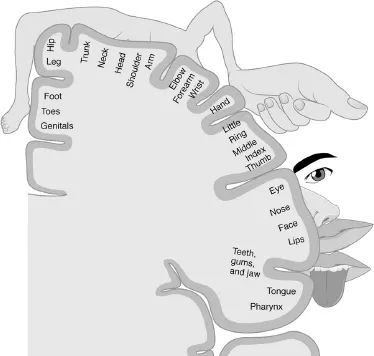

This diagram shows which areas of the brain correspond to the sensory input from different parts of the body. The relative size of the different body parts indicates how much of the brain is involved in processing the signals it receives, hence the hand is shown much larger than the foot.

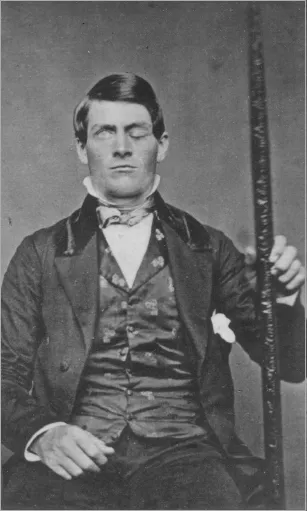

The unfortunate Phineas Gage

The idea that specific parts of the brain might be responsible for different functions originated with the medical case of a railroad construction foreman called Phineas Gage. On 13 September 1848, Gage was seriously injured when a metal tamping iron – a long, pointed rod weighing six kilograms – was accidentally fired through his head. It entered through the cheek and left through the top of his head, taking fragments of his brain with it. He lost a bit more brain when he vomited, and ‘about half a teacup full’ of brain fell on the floor, according to the doctor who attended him. The main damage was caused to one of the frontal lobes of his brain.

Although his friends had a coffin ready and waiting for him, remarkably, Gage (right) lived. However, his personality changed considerably for a long period. Instead of the polite and friendly man he had been before, he became difficult and antisocial – though not the terrible character that legend suggests. His social ineptitude improved with time, and he ended his days working as a stagecoach driver in Chile. It’s possible that the routine of his new life helped in his rehabilitation, as structured activity is found to be helpful in the treatment of many patients suffering damage to the frontal lobes.

In two minds

The brain comprises two halves, or hemispheres. Each hemisphere contains the same structures and there is communication between the two via a thick bundle of nerve fibres called the corpus callosum. How the two hemispheres work together was explained by Roger W. Sperry, a neuropsychologist who treated patients with severe epilepsy by severing the corpus callosum. It sounds drastic, and it was, but it did cure their epilepsy. After he cut the connection between the two hemispheres, the right hand literally did not know what the left hand was doing.

At first the surgery appeared to have little impact on the patients – apart from relieving their epilepsy. But investigation of Sperry’s split-brain patients soon revealed that there had been major changes. In the process, Sperry gained new insights into how the two halves of the brain normally work together.

Sperry found that if he presented a picture to the right visual field (processed by the left side of the brain), the patient could name the object in speech or writing, but if it was presented to the left visual field they could not.

They could, though, identify the object by pointing. From this, Sperry concluded that language is processed in the left side of the brain.

‘[Each hemisphere is] indeed a conscious system in its own right, perceiving, thinking, remembering, reasoning, willing, and emoting, all at a characteristically human level, and… both the left and the right hemisphere may be conscious simultaneously in different, even in mutually conflicting, mental experiences that run along in parallel.’

Roger Wolcott Sperry, 1974

He found, too, that objects shown to the left side of the brain can only be recognized by that side. If he displayed different symbols in the right and left visual fields and then asked the person to draw what they saw, they only drew the symbol shown in the left visual field. If he then asked them what they had drawn (not seen), they described the symbol in the right visual field. Objects originally viewed in the left visual field were recognized if viewed again in the left, but not if then viewed in the right visual field.

Look inside

We no longer need to wait for people to die before we can look at their brains. There are various ways we can monitor or examine brain structure and activity:

•A computed tomography (CT) scan uses X-rays and a computer to produce three-dimensional images of the brain. It shows the normal structure and can highlight damage, tumours and other structural changes or abnormalities.

•An electroencephalogram (EEG) monitors the electrical impulses produced by brain activity. It can reveal the person’s state of arousal (sleeping, waking and so on) and show how long it takes for a stimulus to trigger brain activity or reveal the areas where brain activity takes place when the subject performs an action or is exposed to a stimulus.

•A positron emission tomography (PET) scan reveals the real-time activity of the brain by showing where radioactively-tagged oxygen or glucose is being concentrated. This is because the harder the brain works the more oxygen and glucose it uses. It’s useful for seeing which parts of the brain are used for specific tasks or functions.

•Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) combines radio waves with a powerful magnetic field to detect different types of tissue and produce detailed anatomical images of the brain.

•Magnetoencephalography (MEG) picks up the tiny magnetic signals produced by neural activity. This is currently expensive and not widely used, but provides the most detailed real-time indication of brain function.

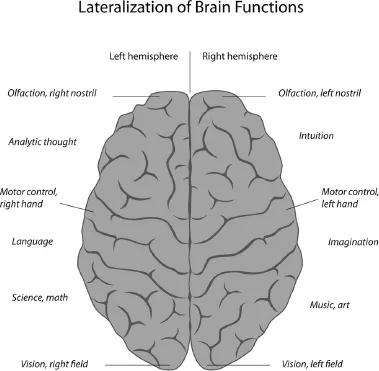

LEFT BRAIN, RIGHT BRAIN?

In popular psychology, it’s common to refer to ‘left brain’ and ‘right brain’ functions or personalities. If the left half of your brain is dominant (or so the story goes), you will be good at logical and analytical thought, and more objective than a right-brain thinker. If the right half of the brain is in charge, you’ll be intuitive, creative, thoughtful and subjective. But it’s nonsense. Almost all functions are carried out approximately equally by both halves of the brain. Where there are differences, there’s variance between individuals as to which hemisphere does more of one thing or another.

The only area of significant difference is in language processing, as discovered by Sperry. The left hemisphere works at the syntax and meaning of language, while the right hemisphere is better at the emotional content and nuance of language. But that’s it – not enough on which to build a ‘left-brain = logical, right brain = creative’ construct.

For the first time, brain scans show psychologists which parts of the brain are involved in different types of activity and behaviour. Comparing brain scans of psychopathic killers, for instance, shows that they all have similar brain abnormalities (see here).

Use it or lose it

If psychologists relied on studying damaged brains for their research, they would make slow progress. Luckily, healthy, functioning brains are just as useful.

In 2000, Eleanor Maguire at University College, London, used MRI scanning to compare the brains of London taxi drivers and a control group of men of similar age and profile. The taxi drivers spend up to four years memorizing routes through the 25,000 streets of London. This is known colloquially as the ‘Knowledge’. Maguire’s study showed that the posterior hippocampus of the taxi driver’s brain is significantly larger than the hippocampus in members of the control group. This research not only indicated the importance of the hippocampus in navigation and spatial awareness but also that the brain (or at least the hippocampus)...