eBook - ePub

A Prehistory of South America

Ancient Cultural Diversity on the Least Known Continent

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Prehistory of South America is an overview of the ancient and historic native cultures of the entire continent of South America based on the most recent archaeological investigations. This accessible, clearly written text is designed to engage undergraduate and beginning graduate students in anthropology.

For more than 12,000 years, South American cultures ranged from mobile hunters and gatherers to rulers and residents of colossal cities. In the process, native South American societies made advancements in agriculture and economic systems and created great works of art—in pottery, textiles, precious metals, and stone—that still awe the modern eye. Organized in broad chronological periods, A Prehistory of South America explores these diverse human achievements, emphasizing the many adaptations of peoples from a continent-wide perspective. Moore examines the archaeologies of societies across South America, from the arid deserts of the Pacific coast and the frigid Andean highlands to the humid lowlands of the Amazon Basin and the fjords of Patagonia and beyond.

Illustrated in full color and suitable for an educated general reader interested in the Precolumbian peoples of South America, A Prehistory of South America is a long overdue addition to the literature on South American archaeology.

For more than 12,000 years, South American cultures ranged from mobile hunters and gatherers to rulers and residents of colossal cities. In the process, native South American societies made advancements in agriculture and economic systems and created great works of art—in pottery, textiles, precious metals, and stone—that still awe the modern eye. Organized in broad chronological periods, A Prehistory of South America explores these diverse human achievements, emphasizing the many adaptations of peoples from a continent-wide perspective. Moore examines the archaeologies of societies across South America, from the arid deserts of the Pacific coast and the frigid Andean highlands to the humid lowlands of the Amazon Basin and the fjords of Patagonia and beyond.

Illustrated in full color and suitable for an educated general reader interested in the Precolumbian peoples of South America, A Prehistory of South America is a long overdue addition to the literature on South American archaeology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Prehistory of South America by Jerry D. Moore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Archaeology in South America

A Brief Historical Overview

Let us come to the rational animals.

We found the entire land inhabited by people completely naked, men as well as women, without at all covering their shame. They are sturdy and well-proportioned in body, white in complexion, with long black hair and little or no beard. I strove hard to understand their life and customs, since I ate and slept with them for twenty-seven days; and what I learned of them is the following.

1502 letter from Amerigo Vespucci to his patron, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici

Current archaeological knowledge builds on several centuries of interest in the antiquities and monuments of South America, although interest motivated by very different goals and practices. The first European descriptions of South American objects and sites were the by-products of conquest. Soldiers accompanying Francisco Pizarro’s expeditions in 1532–33—such as Miguel de Estete and Pedro Pizarro—described the towns and monuments of native kingdoms, in the process providing valuable accounts of the Inca Empire. The soldier-chronicler Pedro de Cieza, who arrived in America as a fourteen-year-old in the 1530s to seek the riches of the New World, was also an astute observer with an eye for detail, describing ancient road networks, fortresses, temples, and other native constructions between Colombia and Cusco. Catholic priests described the ritual artifacts and sites used by native peoples, usually to replace native religion with Christianity. Father José de Arriaga’s 1621 The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru was a descriptive guidebook to Andean religion, listing sacred places and artifacts so local Catholic priests could recognize and eliminate pagan beliefs. A more sympathetic and extraordinarily valuable document was prepared in the early 1600s by the bilingual mestizo author Guaman Poma de Ayala, who wrote a 1,400-page document, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, in which he argued that the Spanish conquest was unjust and the colonial system cruel, supplementing his argument with hundreds of drawings illustrating Andean culture and Spanish inequities. In the early seventeenth century, Father Bernabe Cobo wrote detailed accounts of Inca religion and culture. Although none of these documents were focused on the scholarly study of South American cultures, they are valuable sources of information, particularly about the Incas.

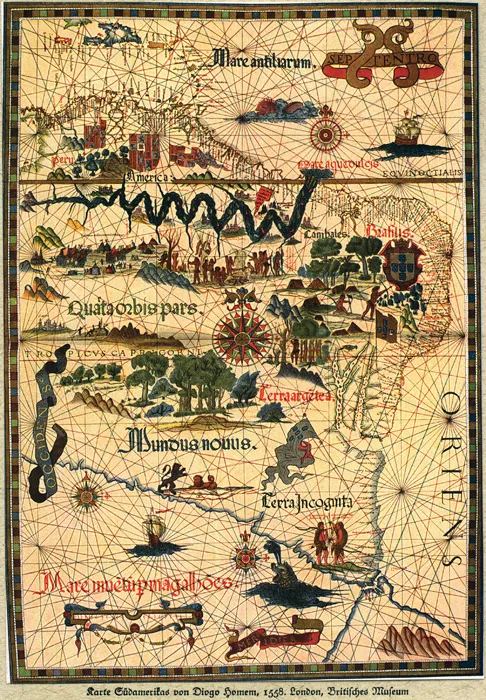

Figure 1.1 A 1558 map of South America

A theme that emerges from these accounts, particularly in the Andean region, was the recognition that—despite the achievements of the Inca Empire—some sites were the creations of earlier peoples, often vaguely described as the huaris (Quechua for “ancestors” or “old ones.”) Some of these pre-Inca cultures had been recently assimilated by the Incas just before the Spanish conquest, and their names were still remembered. One of these cultures was the Chimú of the North Coast, who had been conquered by the Inca only a few decades before the Spaniards had conquered the Inca. Earlier cultures, however, were anonymous and unrecorded by Spanish chroniclers.

Exotic Curiosities and Cabinets of Wonder

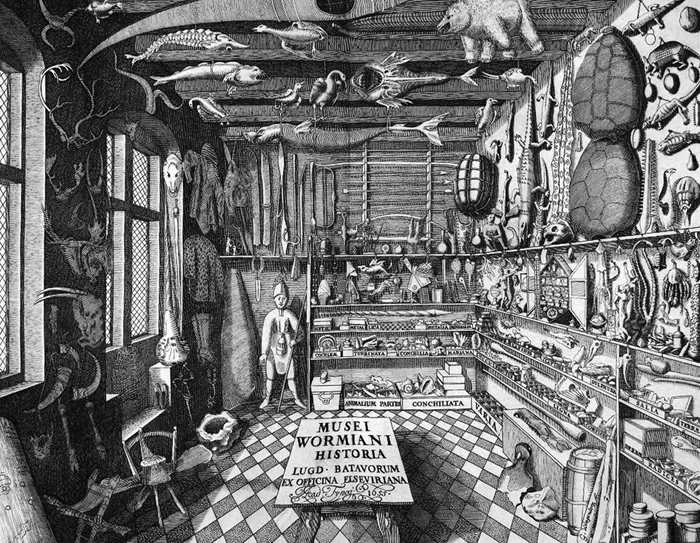

The study of archaeological artifacts and sites had similarly indirect origins. Some objects were shipped from the New World to European monarchs as evidence of their loyal subjects’ conquests, although many artifacts made from precious metals were melted into bullion without regard for aesthetics. As a by-product of Enlightenment concerns, formal collections of natural specimens and other curiosities, so-called cabinets of wonder, were established across Europe, precursors to royal collections and museums (figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 A 1655 cabinet of wonder—frontispiece from Museum Wormianum by Danish naturalist Ole Worm (1588–1655)

In 1752 the Spanish natural historian and diplomat Antonio de Ulloa proposed establishing an Estudio y Gabinete de Historia Natural in Madrid that would house objects Ulloa and others had collected on their voyages. Not until 1771 did the Spanish king, Carlos III, establish the Real Gabinete de Historia Natural, issuing a decree to his global empire to collect and send objects of interest to Madrid. The collections included natural specimens, paintings, and other artworks, as well as antiquities. Opened in 1776 and looted by Napoleon’s forces in 1813, the Real Gabinete de Historia Natural was transformed into the Real Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Madrid, the institutional ancestor of the current Museo de America.

The Spanish clergyman Baltazar Jaime Martinez de Companion, who served as bishop of Trujillo from 1778 to 1790 and whose diocese included the coast, highlands, and jungle regions of north-central Peru, prepared a remarkable nine-volume document known as Trujillo del Peru. Lavishly illustrated with watercolors portraying colonial society, documented with detailed maps and plans, and even containing musical scores of folksongs, the ninth volume of Trujillo de Peru was dedicated to archaeological sites and discoveries. The volume responded to a royal inquiry asking in part “if there exists some work from those times before the conquest; if it is conspicuous due to its material, form or grandeur or such vestiges of it; if, by chance, gigantic bones that appear human have been found; and if some tradition is preserved that at sometime there were giants; and also of the places from which they came, and of their duration, extinction and its causes; and about what leads to the maintenance of said tradition.”1 The good bishop replied to these and many other questions with words, images, and objects. He prepared a map of the Chimú site of Chan Chan, illustrated native mummies, and created a list of words in several non-Quechua North Coast languages. In 1788 Martinez de Companion shipped twenty-eight boxes of curiosities—dried animals, ceramics, utensils, and other objects—to the Real Gabinete de Historia Natural; these boxes have never been found. In 1790 he shipped another six boxes of the ceramics that had figured in his illustrations; some of them have been found and contain nearly 200 ceramic vessels.

South American archaeology originates from the same Enlightenment-era concerns that resulted in the establishment of the first natural history and archaeological museums in Europe but also from the wave of scientific explorations that occurred in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Scientific Explorers, Antiquarians, and Fieldworkers

After the mid-1700s, South America saw numerous scientific expeditions, most focused on fields such as geology, botany, and zoology. For example, some of the greatest scientific explorers in South America—such as Richard Spruce (1817–93), Henry W. Bates (1825–95), Alfred Russell Wallace (1823–1913), and Charles Darwin (1809–82)—mentioned the continent’s peoples and customs in passing, essentially as brief distractions from the plants, animals, and rocks these natural historians had come to study.

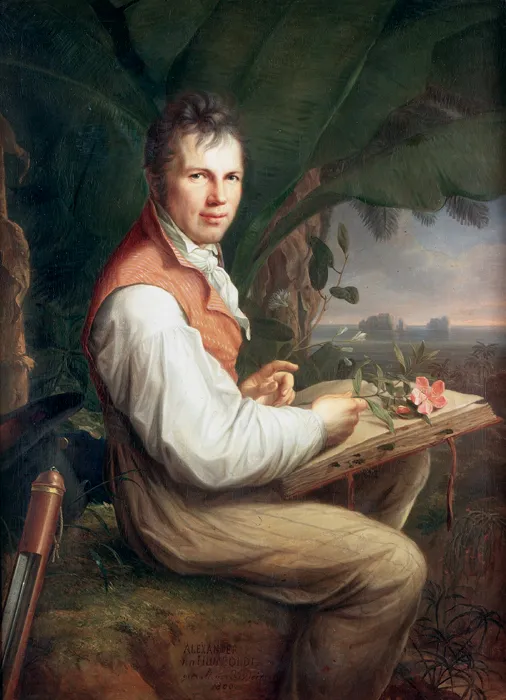

But Alexander von Humboldt was different (figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Portrait of Alexander von Humboldt, 1806, painted by Fredrich George Wietsch (1758–1828)

Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1850) was a scholar who encompassed an astounding variety of disciplines, from astronomy to zoology, from botany to political economy. His extensive explorations in tropical Ameri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Archaeology in South America

- 2 The Brave New World

- 3 The Last Ancient Homeland

- 4 Archaic Adaptations

- 5 Origins and Consequences of Agriculture in South America

- 6 Social Complexities

- 7 Social Complexities

- 8 Regional Florescences

- 9 Age of States and Empires

- 10 Twilight of Prehistory

- 11 Empire of the Four Quarters

- 12 After Prehistory

- Acknowledgments

- Illustration Credits

- Index