eBook - ePub

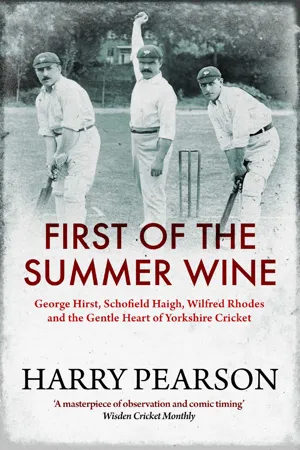

First of the Summer Wine

George Hirst, Schofield Haigh, Wilfred Rhodes and the Gentle Heart of Yorkshire Cricket

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

First of the Summer Wine

George Hirst, Schofield Haigh, Wilfred Rhodes and the Gentle Heart of Yorkshire Cricket

About this book

The remarkable story of three Yorkshire cricketers from the Golden Age - George Hirst, Wilfred Rhodes and Schofield Haigh - who transformed their county's fortunes, inspired a generation of cricketers and left a unique legacy on the game.

Between them, Hirst, Rhodes and Haigh scored over 77,000 runs and took almost 9000 wickets in a combined 2500 appearances, helping Yorkshire to seven County Championship triumphs. The records they set will never be beaten, yet the three men - known throughout England as The Triumvirate - were born in two small villages just outside Huddersfield, in Last of the Summer Wine country. Hirst pioneered and perfected the art of swing and seam bowling, Rhodes took more first-class wickets than anyone else in history, while the genial Haigh's achievements as a bowler at Yorkshire have been surpassed only by his two close friends; their influence would extend far beyond England, as they all went to India to coach, laying the foundations of cricket in the subcontinent.

Pearson, whose biography of Learie Constantine, Connie, won the MCC Book of the Year Award, brings the characters and the age vividly to life, showing how these cricketing stars came to symbolise the essence of Yorkshire. This was a time when the gritty northern professionals from the White Rose county took on some of the most glittering amateurs of the age, including W.G.Grace, C.B.Fry, Prince Ranji and Gilbert Jessop, and when writers such as Neville Cardus and J.M.Kilburn were on hand to bring their achievements to a wider audience.

The First of the Summer Wine is a celebration of a vanished age, but also reveals how the efforts of Hirst, Rhodes and Haigh helped create the modern era, too.

Between them, Hirst, Rhodes and Haigh scored over 77,000 runs and took almost 9000 wickets in a combined 2500 appearances, helping Yorkshire to seven County Championship triumphs. The records they set will never be beaten, yet the three men - known throughout England as The Triumvirate - were born in two small villages just outside Huddersfield, in Last of the Summer Wine country. Hirst pioneered and perfected the art of swing and seam bowling, Rhodes took more first-class wickets than anyone else in history, while the genial Haigh's achievements as a bowler at Yorkshire have been surpassed only by his two close friends; their influence would extend far beyond England, as they all went to India to coach, laying the foundations of cricket in the subcontinent.

Pearson, whose biography of Learie Constantine, Connie, won the MCC Book of the Year Award, brings the characters and the age vividly to life, showing how these cricketing stars came to symbolise the essence of Yorkshire. This was a time when the gritty northern professionals from the White Rose county took on some of the most glittering amateurs of the age, including W.G.Grace, C.B.Fry, Prince Ranji and Gilbert Jessop, and when writers such as Neville Cardus and J.M.Kilburn were on hand to bring their achievements to a wider audience.

The First of the Summer Wine is a celebration of a vanished age, but also reveals how the efforts of Hirst, Rhodes and Haigh helped create the modern era, too.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access First of the Summer Wine by Harry Pearson in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Simon & Schuster UKYear

2022Print ISBN

9781398501546eBook ISBN

9781398501539CHAPTER ONE The Baby from the Brown Cow

Many legends swirl around George Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes. The first of them attests to the fact that George Herbert was born in 1871 on the opening day of the first ever Scarborough Cricket Festival, an event he’d adorn for four decades, where he’d take wicket 200 in the season of the ‘double double’, play his final game for Yorkshire and make his last appearance in first-class cricket, aged 58.

That 1871 match was played, not at North Marine Road, but in the old ground on Castle Hill between Lord Londesborough’s XI and a team of Scarborough Visitors led by Charles ‘Bun’ Thornton. Thornton, who refused to wear gloves or pads, was one of the biggest hitters of a cricket ball in the Victorian age. At the Scarborough Festival in 1886, playing for the Gentlemen of England, ‘Bun’ would score a century with just 26 shots, one of which was a straight drive that was said to have travelled 162 yards before bouncing. Thornton had been born and raised in Herefordshire and had no familial or other connections with Scarborough, but he loved the seaside resort and would soon take over running the cricket festival, make a huge success of it, and along the way become a great friend and admirer of George Herbert.

So, if George Herbert had been born on 11 September 1871, the day Bun Thornton took the field in Scarborough for the very first time, it would have been a happy coincidence for cricket. Unfortunately, he made his entry into the world a few days earlier, on 7 September.

The other circumstances of George Herbert’s birth are altogether more opaque. We can say with some certainty that he was born in the Old Brown Cow Inn, off St Mary’s Lane in Kirkheaton. The Old Brown Cow was an alehouse that belonged to the Whitley Beaumont estate. In 1871 James Hirst ran the inn and farmed the six acres of land attached to it. This was part of a long-standing arrangement. When local magistrates threatened to remove the pub’s licence in 1927, those opposing the closure claimed the Hirst family had been running the pub for over a century and that 50 members of the clan had been born in its rooms. The magistrates, unswayed by sentiment and tradition, shut the Old Brown Cow down. After the Second World War the local council made sure the pub would never return – whether run by Hirsts or not – demolishing it so they could widen the road to Leeds.

George Herbert was, by most accounts, the 10th child of the pub’s landlord, James, and his wife, Sarah. He had four brothers (Thomas, James, Job and Henry) and five sisters (Mary, Hannah, Sarah, Amelia and Louisa). Hannah had died in infancy and Mary, the eldest, had been born before James and Sarah married and had her mother’s maiden name, Woolhouse. After his father, James Hirst, died in 1880, George Herbert went to live with his sister Mary and her husband, John Berry, in New Street, Kirkheaton. In the 1881 census, George Herbert Hirst is listed as living at that address. He’s also described as being the son of Mary and John Berry. This could be a simple error, or, in a plot twist straight out of Barbara Taylor Bradford, it may be that George’s sister was actually his mother and those everyone thinks of as his mother and father were, in fact, his grandparents.

If there was gossip it does not seem to have bothered young George Herbert. And in Kirkheaton and its environs it was always George Herbert, never simply George. Some took this as a sign of deference, or Victorian formality. It may have been a bit of both. More likely, though, it was to make conversations shorter and simpler. There were thousands of Hirsts around Huddersfield, hundreds of them playing league cricket. In the days when men’s forenames were drawn from a very shallow pool, with Georges, Josephs and Williams predominating, calling someone by both their given names was a short cut to understanding. It was far speedier than explaining who you meant through family reference.

In my grandfather’s clan, where every other male seemed to be called Alfred, whole afternoons and evenings could pass after somebody said, ‘No, not Old Alfie’s Young Alfie, Young Alfie’s Alfie, the one that married Our Alfie’s lass. You know her, she was Fat Alfie’s niece’ and wind onwards from there until everyone was dizzy or had gone to the pub. Calling him George Herbert likely saved hours of spiralling confusion.

George Herbert’s childhood among the sprawling mass of the Hirst family was a happy one. He recalled helping his father, James, drive the cattle to milking, but otherwise played cricket from noon till night. ‘At the Old Brown Cow we played our cricket in the yard and on the intake field below.’

Kirkheaton squats on the slopes of the Pennines. The houses are made of grey Crosland Hill stone that glows on sunny days and grimaces on damp ones. There are a lot of damp ones. Nowadays, the valleys around Kirkheaton are the haunt of day-trippers, hikers and weekenders. On sunny afternoons, retirees park up on verges, fold out a picnic table and eat vanilla slices while looking out across the wild-flower meadows and sucking in the moor-top air.

It was a very different place when George Herbert was young. Smoke from the mills and factories and the hundreds of thousands of domestic chimneys curled up into the Yorkshire sky and fell back as soot. Tons of the fine black powder pattered down each day, darkening buildings, giving hedges and trees a funereal topcoat, dyeing sheep grey and playing havoc with the laundry. The people worked and played in it. They breathed it in. Coughs and sneezes left sombre blotches on cotton handkerchiefs. Asthma, bronchitis and other lung complaints carried off dozens daily. The manufacturing of cloth did not seem as inherently risky as mining or smelting iron, but it was hazardous all the same. The shuttle looms, rattling like machine guns, were a constant threat to the limbs of the unwary. In 1818, the village cotton mill had caught light, the fibres that hung in the air creating a fireball that burned to death 17 female workers, some of them as young as nine. George Herbert was born into a world that would have made Monty Python’s ‘four Yorkshiremen’ wince.

The village already had a tradition of cricket. It was the birthplace of Andrew Greenwood and Allen Hill, two of the five Yorkshiremen who played in the first-ever Test match, at Melbourne in 1877. The cricket field, established in 1883, sat then, as it does today, on a flat headland facing towards the chimneys of Huddersfield. It’s flanked by drystone walls and scoured by the moorland breeze. Across the valley, you can see the field and pavilion of Lascelles Hall. One of England’s oldest clubs, Lascelles had a side so strong that three years before George Herbert’s birth they’d beaten an All England XI and three years after it they took on the full Yorkshire team in a two-innings match and stuffed them by 146 runs. Among their stars were Ephraim Lockwood, John Thewlis and Billy Bates, the first Englishman to take a Test hat-trick. If George Herbert needed role models, he didn’t have to look far.

He joined Kirkheaton Cricket Club in 1884 and spent so much time on the ground at Bankfield Lane, the little wooden pavilion was like a second home. George Herbert would later recall how at Kirkheaton when the players had ‘nets’ they were nets in name only. There were no actual nets. Every ball that was hit had to be fielded.

By then he had already left school. Aged 10 he’d been taken on as a wirer for a Kirkheaton handloom weaver who lived in a cottage on the road to Lascelles. His employer did little to encourage the youngster’s cricketing ambitions. George Herbert would later recall that the man had no interest in the game and ‘spent all his brass backing horses’.

His first proper cricket match was in 1885, an away fixture for Kirkheaton Seconds against Rastrick Seconds. George Herbert was supposed to play as a bowler, but wasn’t needed. He made up for the disappointment by hitting 20 with the bat. He made more appearances for Kirkheaton Seconds that season, and the following year was promoted to the first team. By now he was working at Robson’s Dye House across the valley from the Old Brown Cow.

Filling out as he hit his mid-teens, George Herbert had started playing rugby for Mirfield. The game had not yet split between amateur and professional codes. George Herbert played centre in a three-quarter line that included the future England star Dickie Lockwood. Lockwood was so impressed with Hirst he wanted him to move with him to a higher level at Heckmondwike, but by then George Herbert’s focus had shifted back to cricket again.

The change had come in 1889 when George Herbert was 17 and Allen Hill arrived to coach Kirkheaton before the club’s campaign in the Lumb Cup. Hill was the first man ever to take a wicket in a Test match. He’d played for Kirkheaton and Lascelles Hall before moving on to Yorkshire, where his fast round-arm bowling earned him 749 wickets. His career had been ended six years earlier by a badly broken collarbone. He was working as a wool weaver but when asked for his profession still proudly said ‘cricketer’. Hill was genial and cheery. His coaching must have been good too because Kirkheaton ended the season with their first trophy, winning the Lumb Cup after defeating Cliffe End in the final. The match was watched by a number of Yorkshire players. George Herbert excelled with the ball, taking five wickets for 23. When Yorkshire played Cheshire at Fartown, Huddersfield, a week later, Hirst was invited to join them.

He travelled the short distance to the game in some trepidation, less because he feared the opponents, but because he was worried about his clothing. George Herbert had a pair of brown boots, white trousers held up with a snake belt and a thick cream jumper he’d have to keep on no matter what the temperature because the shirt underneath it was blue. He needn’t have worried. He was better off than several of the other trialists – they didn’t have shirts at all. George Herbert bowled decently in Cheshire’s first innings, picking up three wickets, but when the game ended Yorkshire gave no indication they’d want a second look.

By now, however, his exploits at Kirkheaton – where on August Bank Holiday he’d taken nine Mirfield wickets for a handful of runs – had drawn attention and Elland took him as a ‘Saturday man’ for the 1890 season. This was not a full-time professional post, which would also have involved net bowling and tending the ground, but a pay-by-the-game arrangement. George Herbert used the first £4 he earned to buy himself a white shirt. He already had a canvas bag for his kit, which put him ahead of the great Tom Emmett, who in his first few appearances for Yorkshire had carried his equipment to matches rolled up in a newspaper. Emmett, it should be said, was also noted for the colour of his nose, which was said to be so red that any fly that landed on it burned its feet.

George Herbert was selected to play in two games for Yorkshire during the 1890 season. Against Staffordshire at Stoke in June he was given limited chances to shine. In his next outing, against Essex at Leyton, he performed poorly, failing to get a wicket or score a run.

In 1891 George Herbert moved to Mirfield as Saturday man. Yorkshire picked him for the match with Somerset at Taunton in late July. Again, his performance was mediocre, 15 runs and two wickets. Other cricketers in Hirst’s time would make a great impact at Yorkshire only to be dropped as soon as they failed and never be seen again. His chances were running out.

The turning point came when he was picked in early May 1892 to play at Lord’s against MCC and Ground. He batted well, scoring 20 and 43 not out, and took six wickets in the match. The performance at Lord’s earned him a place in the Yorkshire team to play Essex at Dewsbury. He did well enough to retain his place when Sussex came to Sheffield. Things began badly. After Sussex had scored 177 in their first innings, Yorkshire were bowled out for 81 and forced to follow on. Ted Wainwright rescued the second innings by scoring a century and the visitors were set 137 to win. They were three down for 51, when Lord Hawke threw the ball to George Herbert. He had not had much of a game so far. He’d bowled 11 tidy but unproductive overs in the visitors’ first knock, come in at number 10 to score a duck and one not out. Now, perhaps sensing it was his last chance, he charged in, bowled fast and straight, and ran through the Sussex batting like a ram through a wheat field, taking six wickets for 16 as they collapsed to 96 all out.

After he’d skittled out Sussex, George Herbert was so chuffed he abandoned his normal modesty and told Yorkshire’s secretary, Joseph Wostinholm, ‘I’ve got into the team now, and I am going to keep my place. If I can’t do it with my bowling, I’ll do it with my batting.’ He was 20 years old and brimming with confidence. No matter what happened, he’d never lose it.

When George Herbert made his debut for Yorkshire in the 1889 season it was not a happy time for his native county. That great early chronicler of the White Rose game, the Reverend Holmes, called it, ‘the low-water mark of Yorkshire cricket’. Yorkshire spent the first two months languishing at the bottom of the County Championship. They lost 10 matches and won just two, defeating Sussex in the penultimate match of the season to avoid finishing last.

The batting was feeble – a situation highlighted in the game against Kent at Halifax, in which Yorkshire were shot out in the first innings without a single batsman making double figures. The decency of the bowling, meanwhile, was undermined by fielding so hopeless it could have been as well done wearing blindfolds and oven gloves. Dozens of catches were spilled and hundreds of runs conceded by fielders whose co-ordination often seemed adversely affected by meal breaks. It was plainly time for drastic action, and luckily Yorkshire had just the man for the job.

Lord Hawke was tall and strapping, with a walrus moustache and keen, steady eye of a Wild West marshal. He had taken over the captaincy of Yorkshire in 1883, while still a student at Cambridge. An Old Etonian whose family lived at Wighill Park near Tadcaster, Lord Hawke would rise to a position of great prominence and power within the game and, along with Lord Harris of Kent, form a duo that was referred to – not with great affection – as the Dukes of Cricket. A Conservative politician, Lord Harris would serve as under-secretary of state for India and governor of Bombay. Lord Hawke would become president of Yorkshire County Cricket Club. To Hawke’s mind, and to those of all right-thinking people, it was clear who had achieved the greater position.

That was for the future. For now, Lord Hawke found himself confronting a scene that might have daunted other young men. The Yorkshire team he had inherited was both supremely talented and a byword for roughness and dissolution. J. M. Kilburn commented in his usual mild way that the side had ‘fallen prey to the temptations on offer to cricketers of the time’. Others put it more bluntly. Yorkshire’s starting XI consisted of ‘ten drunks and a parson’. The ‘parson’ was opening batsman Louis Hall, a nonconformist preacher from Batley who batted like he was facing Judgement Day. Walking into the Yorkshire dressing room in 1883 was like entering a Dodge City saloon when the cattle drives had arrived.

Lord Hawke took his time reaching for his six-guns, but in 1887 he kicked open the doors and came in shooting. His target was the greatest spin bowler of his generation, Ted Peate. Peate was born in Holbeck, Leeds, then one of the grimmest slums in the industrial world. He bowled slow left-arm with an action of such lazy elegance it practically purred. Peate played nine times for England. Most famously, or perhaps infamously, he came in last man against Australia at The Oval in 1882, with 10 runs needed and the accomplished Middlesex batsman Charles Studd at the non-striker’s end. Peate was expected to block out the deliveries remaining in Harry Boyle’s over and then let the stylish Studd – an Old Etonian evangelical Christian – try to make the winning hits. Instead, he took a series of mighty heaves and was clean bowled.

When asked what he had been playing at, Peate replied simply, ‘I could not trust Mr Studd to get them.’ Today this remark seems either mildly idiotic, or an entertaining illustration of the North–South divide, but in Victorian England it was viewed as pernicious truculence. Peate’s file was marked. The following day the Sporting Times ran its death notice to English cricket. Ted Peate, from the smoggy, cholera-ravaged purlieus of Leeds, had inadvertently created the Ashes.

Undaunted by the furore about his behaviour, Peate returned to Yorkshire and the following season took 214 wickets – a first-class record. W. G. Grace cooed over the spinner’s style and poise, while Yorkshire’s wicketkeeper, David Hunter, reckoned him ‘the finest left-arm bowler I ever saw’.

Peate had once taken eight wickets for five runs against Surrey on a wet wicket, but he was equally effective on dry, hard pitches. Pace and flight as much as spin were his weapons and he was as accurate as the time signal. On the field he was a wonder of the age, off it a shambolic mess, disappearing into pubs as soon as play finished for the day and joining his gang of well-wishers, who bought him drink after drink. Soon the same mob started accompanying him to matches too, and their idol would join them in the beer tent during the lunch and tea intervals. In 1887, Peate was still bowling brilliantly, but his behaviour was so erratic and his entourage so brutish and foul-mouthed, Hawke banished him just three matches into the season. For Yorkshire there was no need to worry. His replacement was earmarked. He was a pitman’s son from Morley, who not only bowled like an angel, but was a thumping left-hand bat and caught the ball as if he had suckers on his fingers. His name was Bobby Peel.

Nor was Hawke finished with his clear-out. After the 1889 debacle he took aim again. Out went four experienced players whose talents on the field had been compromised by their behaviour off it: Fred Lee (who’d hit 165 in a Roses match), all-rounder Saul Wade, Irwin Grimshaw (who’d scored a century in each innings in a match with Cambridge University) and off-spinner Joe Preston (best figures: nine wickets for 28 against MCC). It was perhaps a measure of the life of a professional cricketer at that time that only one of the men Lord Hawke fired during this spell would survive beyond the age of 50.

Hawke set about replacing the banished reprobates with younger, more solid and decent professionals. George Herbert would be one of them. He was joined by opening batsman John Tunnicliffe, a devout Methodist, the loyal wicketkeeper David Hunter (whose chief vice was playing the concertina) and Tunnicliffe’s opening partner, Jack Brown, from Driffield in the East Riding. Doubtless there were those at the time who bemoaned the fact that Hawke’s policy meant there were ‘no longer the characters in the game that there used to be’, but for a young man such as George Herbert, making his first steps as a professional, the clear-out of these hard-living, rough-edged rogues must have made life a lot cosier.

Tunnicliffe had been such a prodigy as a boy, his local club Pudsey Britannia had changed their rules to allow him to play for them when he was 16. He was enormously tall for the time – around 6ft 4 – and as a youngster a massive hitter. In 1891, playing for Yorkshire Colts against Nottinghamshire Colts, he smashed a ball from Baguley over the old Bramall Lane pavilion and into the backyard of a brewery on the other side of the road. When he reached the Yorkshire first team that same year he modified his game, became more cautious and orthodox, getting his long leg well down the pitch. If Long John’s batting was not always thrilling, his slip fielding made up for it. He caught equally well with right and left hand and, unusually among fieldsmen of the time, he was prepared to dive full-length to grab the ball. The sight of his large body, pale clothing and bristling moustache arcing above the earth called to mind less a salmon or a dolphin than a walrus.

His batting partner Jack Brown was his exact opposite in many ways. Compact and quick on his feet, he was forcing rather than forceful, an attractive player to watch with a range of drives, pulls and cuts. He was a brilliant outfielder too, fast across the ground with a flat accurate t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Prelude: The Men in the Postcard

- Chapter One: The Baby from the Brown Cow

- Chapter Two: The Sunday School Pro

- Chapter Three: The Boy in the Barn

- Chapter Four: The Triumvirate Triumphant

- Chapter Five: Swerve

- Chapter Six: Singles

- Chapter Seven: Doubles

- Chapter Eight: Titles and Changes

- Chapter Nine: Tours and Tragedy

- Chapter Ten: Bed and Cricket

- Chapter Eleven: The Trouble with Mr Toone

- Chapter Twelve: The Birth of Grim

- Chapter Thirteen: The Fading of the Light

- Chapter Fourteen: On Towards Twilight

- Photographs

- Statistics

- Index

- Copyright