- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

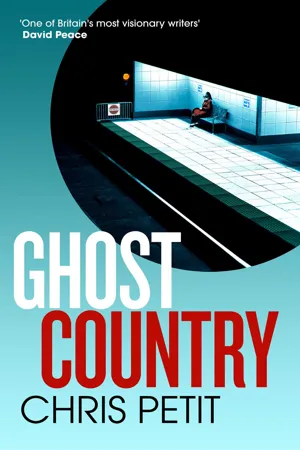

Ghost Country

About this book

From the bestselling author of The Psalm Killer and The Butchers of Berlin

'One of Britain's most visionary writers' David Peace

A breath-taking contemporary thriller for readers of Robert Harris, John le Carré and Martin Cruz Smith

When a government minister is shot there are many suspects but few leads. Days before the attempted assassination, Charlotte Waites, a Home Office analyst, dismissed a crucial intel flag and now has to account for her actions. Dragged into a web of intrigue that will draw in everybody from the prime minister to her ailing father, she must try to get the bottom of the mystery while confronting dark secrets from her family's past.

Complex, gripping and deftly-handled, Ghost Country is work of staggering imagination that, from Northern Ireland to Covid, looks at the complexities of Britain's recent history and distils them into an unforgettable literary thriller.

'One of Britain's most visionary writers' David Peace

A breath-taking contemporary thriller for readers of Robert Harris, John le Carré and Martin Cruz Smith

When a government minister is shot there are many suspects but few leads. Days before the attempted assassination, Charlotte Waites, a Home Office analyst, dismissed a crucial intel flag and now has to account for her actions. Dragged into a web of intrigue that will draw in everybody from the prime minister to her ailing father, she must try to get the bottom of the mystery while confronting dark secrets from her family's past.

Complex, gripping and deftly-handled, Ghost Country is work of staggering imagination that, from Northern Ireland to Covid, looks at the complexities of Britain's recent history and distils them into an unforgettable literary thriller.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

‘There is no such thing as remission, only undiagnosed illness,’ her father told Charlotte Waites as they sat eating a late Christmas lunch. She stared at the array of pills in front of him. His recent health scare had turned out to be a false alarm but the battery of medication remained formidable.

They were in the old dining room, rarely used these days, with the silver service.

‘This is where your grandmother used to entertain her lawnmowers for tea.’

It was a story he often told, how when still merely eccentric she treated the several machines she owned to her hospitality rather than the man who mowed.

Charlotte remembered another Christmas meal in the same room when she was a child. It was the only time she had seen her grandmother tipsy, on sherry, after which she spent the meal singing music hall songs to herself in a low birdlike trill. Towards the end of her life, her grandmother had ended up in the care home over the road after she had taken to wandering around local shops in a state of undress.

Charlotte had been fifteen the last time she saw her, one wet summer afternoon, in the home’s day room, her chair apart from the other residents, who sat slumped in front of a television watching a film – from what she could hear Charlotte guessed Planet of the Apes – until one rose, staggered forward and changed channels, causing an uproar that brought staff running. The film was returned to and the residents resumed their comatose state.

Her grandmother ignored the disturbance. She had hunted in her younger days, riding sidesaddle, with the straightest back in the county. Now she sat vacant. A paperback lay on her lap. Charlotte asked what she was reading. The Belstone Fox, her grandmother said, passing it over with a sly smile. She hadn’t put her teeth in. The dog-eared copy was so splayed it reminded Charlotte of an accordion. Inside she found a quarter of a partly eaten ham sandwich, covered in a green mould, squashed flat between the pages. She shut the book, and made a show of reading the cover, fearing her grandmother’s madness awaited her.

Her father had lived in the house since retiring. It was a plain construction, dating from the early 1950s when there were still post-war building restrictions. Set well back from a road of dreary bungalows and houses, it stood in an acre of walled garden whose size was out of all proportion to the modest three-bedroom house. What Charlotte remembered as an enchanted space kept by her grandmother – mowing, weeding, pruning and even scything – had been allowed to run wild. Only the lawn immediately behind the house was occasionally mown by her father in summer. The rest was a jungle of holly thickets, towering brambles and invasive conifers planted by her grandmother, which obscured the view of the Malvern Hills beyond.

Charlotte had driven down empty motorways that morning and would stay for Boxing Day, before going on to Cheltenham for work. Cheltenham was forty minutes away, her father said; she was welcome to stay on and commute. Thanks all the same, she replied, trying to sound grateful, but she was booked in to a Premier Inn that was paid for.

The holiday was spent observing rituals to which neither subscribed: tree, presents and even a stocking for her, for fuck’s sake – at thirty-two! – using the same old pillowcase with her childhood Pentel drawing of a Santa. This annual get-together, which more resembled a hangover of Christmas past than any present celebration, was all rather strange to Charlotte because her father was not nostalgic or sentimental. There wasn’t a photograph to be seen in the house of her mother, dead ten years, or of herself, and her father’s passage through life seemed to have gone unrecorded. This struck her as odd because he made a point of being seen as outgoing and charming, taking time to chat with local shopkeepers and so on. Over the years she had grown resistant to his charm, perhaps because she had refused to cultivate such a quality herself, mistrusting it as a male trope. She took more after her mother, reserved and sometimes sullen. She had worked hard to free herself of her mother’s influence, being professional, competent and even ambitious, but she knew that withdrawal was her fallback position.

Once, during the protracted conflict of the last years of her parents’ marriage, her mother had hissed to her while standing at the kitchen sink, ‘He has a wank magazine in his sock drawer!’

Charlotte remembered being more surprised by her mother’s language than the observation. The exclamation invited no response and there was nothing she could think of or wanted to say.

Although still eligible, and not so old, her father seemed to have made no effort to find anyone else after her mother died, so Charlotte presumed he maintained a regime of self-maintenance via the sock drawer (which she had never looked in, despite being tempted).

Her father had been in military intelligence, about which he was vague, apart from occasional mention of the Warsaw Pact and Northern Ireland. Charlotte suspected her own recruitment to the Home Office had had something to do with him. She had been approached after a couple of years of drifting through jobs following university, without ever considering such a career.

She still had trouble thinking of herself as a grown-up around her father.

She watched his stiff farewell wave in the rearview mirror as she drove away on the morning of 27 December. She crossed the river at Upton and took the motorway to Cheltenham. She was glad to have got Christmas over. She didn’t even turn on the radio for company, brooding instead about work, its atmosphere of bullying and constant cuts. Hopkins had been brought in to steer what was known as the Leadership Team. The woman wasn’t much older than her; had been friendly at first, but soon showed herself to be fast, intolerant, and expert at covering her back. There was her irritating cock of the head to signal disbelief and her talent for derailing any argument by correcting irrelevant details. Charlotte didn’t know why Hopkins was picking on her. No one had before and she was ill-equipped to deal with it. She had been slow to realise that Hopkins was a refinement of the classic bully, clever enough to avoid accusation while selecting juniors to be the target of others’ aggression, sacrificial figures in waiting.

The Home Office was not an employer to offer much hope or instil confidence, and under Hopkins office politics had become aggressively polite and deadly. Their jobs were in doubt. DAD, the Department of Analysis and Data, had been created before Charlotte’s time, to liaise with European security services in response to a technological revolution that still very few understood. Since leaving Europe it had fallen out of fashion, failed to compete and was underfunded as a result.

Before Hopkins, the office’s reputation was for casual internal security. Thanks to her reforms, Charlotte had found herself in trouble after breaching a new rule requiring any computer left unattended, even during a coffee or toilet break, to be logged off. Nobody bothered because of the time it took to log on again. Hopkins’s response to this was to make secret checks, using technicians pretending to be researchers. It was because of a summons by Hopkins that Charlotte had left her desk in the first place. As no one else was reported, she wondered if she had been called in because Hopkins wanted to catch her out.

The incident became connected in Charlotte’s mind with the point of the meeting and whether that too wasn’t as random as it had appeared. Hopkins had told her to check an intel flag that would not normally have required a face-to-face. According to Hopkins, it was because she was still getting to know her staff. A regular complaint of hers was to ask what anyone actually did.

The intel flag Hopkins wanted her to check mentioned a plan to assassinate a leading British politician. The source was a Russian site known for hacking, in this case emails and material belonging to a Dublin-based freelance journalist by the name of Brindley.

Charlotte rang him. Elderly, with a boozer’s voice, both defensive and embarrassed because he had been foolish and responded to a phishing email. He insisted the assassination rumour had been inserted. He said he was old enough to know not to send inflammatory material that could be read by the huge network of security checking machines. Smart enough to know that, Charlotte thought, but mug enough to fall for a phishing email.

Other tainted material, according to Brindley, included mention of a Russian oligarch and his involvement in African sex trafficking and child prostitution. Brindley claimed he had never heard of the man.

She ran checks on the oligarch, a UK resident with a London address, who appeared to spend most of his time at another home in Liechtenstein. Her enquiries revealed that the London house was empty while being renovated. She checked the local residents’ register and noted that a near neighbour was Secretary of State Michael McCavity. She ran his and the names of other prominent politicians through GCHQ’s Tempora system, applied the appropriate trigger words and drew a blank, apart from one mention of McCavity on a Muslim hate site, calling him ‘a mad dog deserving to be put down’.

Checking far-right and Islamic extremist platforms produced no sign of any intended attack.

The accusations of financial and sexual skulduggery against the Russian had been picked up by other sites. One noted the man’s close association with Conservative MPs with no mention of the secretary of state. When Charlotte checked further on the internal Home Office system, she found full access to the Russian’s file blocked. She concluded he fell into the category of yet another suppressed political report on Russian connections to the Conservative Party and left it at that as he wasn’t the point of the enquiry.

By then she had decided Hopkins had probably set her the task as part of some secret internal assessment. There was talk of redundancies. She concluded that the intel flag was standard disinformation, reported it as such, and told Hopkins she had taken it as far as she could and the matter of the oligarch should be further investigated by someone with a higher clearance than herself. Because of the proximity of the minister’s address, she recommended that his security team be advised of the situation. And that was that, however much she sensed Hopkins’s disapproval at her lack of what were called ‘decision-making skills’.

Given the couple of crap jobs she had been assigned over Christmas, Charlotte decided she had failed the test, whatever it had been, and was quickly becoming surplus to requirements within the department.

Situated on a ring road in Cheltenham, GCHQ’s once futuristic design resembled a large, grounded flying saucer. In that deprecating English manner it was known as the Doughnut. The huge site reminded Charlotte of a planeless airport whose perimeter was given over to parking for five thousand cars. She was always struck by how this huge manifestation of the secret state stood in contrast to the staid Regency town. She could never quite see the point of Cheltenham.

Her next three days were spent in windowless basements, monitoring a recruiting exercise involving bright young technicians playing cyber war games. Only the numbered shirts of the examinees – most of them little more than school kids – indicated that an attack on a nuclear power station or a financial institution, which then escalated to include transport and utilities, might not be real. The tense atmosphere, the banks of monitors and subdued high-tech surroundings stood in contrast to the ramshackle set-up of Charlotte’s London office, scarred by cutbacks, massive arse-covering and no sense of collective responsibility. General demoralisation had allowed a ruthless, buccaneering spirit to flourish at the top, which Charlotte had seen previously in the financial sector, only because it had been her misfortune to have briefly gone out with an investment banker.

Boyfriends she had never quite got the hang of. They had been selected from a small pool, usually work-related. What she thought interested her about someone usually turned out not to be the case. She was currently living with ‘Clive’, whom she found it hard to think of without the quotation marks. ‘Living with’ was rather overstating it. She shared his Barbican flat, which belonged to his parents, in exchange for paying rent and sex. For her, among the advantages of the relationship – Clive was quite eligible – were far better accommodation than the over-expensive shared rentals she was used to, whose standard of living was little better than when she had been a student. She in return was dutiful, tidied up after herself and cooked most of the meals because she was the better cook.

Part of her time in Cheltenham was spent having to listen to expensive consultants advise on how to make GCHQ recruitment more attractive. For all their flip charts and designer clothes, they offered the usual rehash of more social media, more neuro-diverse candidates to improve teamwork; more gamers, freaks and geeks; more summer schools; more black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds – none of which addressed why anyone would want to work there rather than be in London, or why they would sign on for a government department that could not compete with civilian salaries.

Charlotte’s Premier Inn was down the wrong end of the high street. Looking for somewhere to eat, she soon found herself in a stretch that reflected the town’s collapse. Several Polish stores were boarded up. The sweet shop had ceased trading. Cheltenham Kebabs-Burgers she didn’t trust. The Oriental Food Store was still in business but closed, as was the halal butchers. The one pub looked an unwelcoming dive. The one tea room was shut. Two Chinese takeaways in a row seemed to cancel each other out, as there were no takers in either.

She gave up and made do with a snack from the hotel vending machine.

After three days of dull work and two dreary Premier Inn nights, rather than drive to Birmingham and an identical hotel room for her job the next day, Charlotte turned off back to her father’s, which was more or less on the way. She had meant to phone, thinking if he was out she would drive on. She was setting a sort of test, she realised, by surprising him to see if he really was pleased to see her.

Instead, she managed only to mess up his plans. She saw this immediately upon his opening the door and saying he had been expecting someone else.

Anyone she knew, she asked, thinking it must be a woman. Just a chum from army days, he told her. Charlotte knew most of them by name but not this one, who sounded Greek. She made polite noises, saying she didn’t want to be in the way; she had just stopped off as she was passing. Her father over-insisted that she stay.

The friend turned up soon afterwards with an overnight case, after taking the short walk down from the station, which suggested he had visited before. He was good-looking in a Mediterranean way, maybe twenty-five years younger than her father, who was in his late seventies. Charlotte sensed the man was thrown by her presence. They ate an awkward supper of cold ham and salad, which she prepared and tidied away. Her father and his guest made polite conversation. Charlotte suspected she was in the way and shooed them off to the pub, watched television for an hour and went to bed early, unsettled by her intrusion. She supposed her father had wanted to talk shop but was inhibited by her presence. The friend, introduced as Dimitrios, puzzled her. Her father’s regiment could not have been more English and friends throughout his life were drawn from the same class and background. Being nosy, she had asked how they had met and was told through NATO. The man’s English was faultless. He said he was stopping off on his way up north.

She was woken by someone getting up in the night and heard the toilet flush. After that she lay awake fretting about work. Once fast-tracked, she was not any more it seemed. It was too late to call Clive, who was with his mother whose short-term memory was shot, confining her to endless repetition that Clive, in one of his funnier moments, said was like being in a Beckett play.

Charlotte left before the others were up and drove for an hour down the motorway to Birmingham International Airport, where she conducted two days of internal security reviews. More meetings in airless spaces among men of questionable personal hygiene; grey faces, beige carpets, plastic cups, watery coffee, no biscuits (budget cuts). The exercise was to test Border Force’s internal security by sending Home Office staff posing as terrorists through immigration channels to see if they were picked up. They nabbed one and missed three. More meetings, more excuses. They were short-staffed because of illness and the holiday season. If morale was low in the Home Office it was rock bottom in Border Force. Charlotte listened to complaints that staff dispirited by pay freezes were being put under intolerable strain with longer hours, mounting caseloads and unrealistic targets. Most recruits quit within months, which left them relying on temporary staff with minimal training. The overall mood was dismal. She sighed at the thought of writing her report. Hopkins, a can-doer, was intolerant of bad news.

It was dark and starting to rain as Charlotte set out for London. The motorway was full of returning holiday traffic. Lorries were chucking up spray that reduced her visibility, which was already hampered by defective wipers. Her Astra was part of the office pool, unloved and poorly serviced. It smelt of something unpleasant and unidentifiable.

The rain fell harder. Charlotte didn’t trust the car at more than fifty-five. She tucked into the inside lane, keeping her distance from the muck thrown up by the vehicle in front, which only left a space for the lorry behind to overtake and force her to repeat the process.

The squeak of the old wipers became like a mantra, leaving her in danger of drifting off. She stopped at the next service station. It was crowded and she sat and watched the people go about their distracted post-Christmas business with a look of those who could not quite believe what they had signed up for. Nothing had ever really returned to normal after the events of the last few years, though everyone tried to pre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Epigraph

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ghost Country by Chris Petit in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.