![]()

An Introduction to Magical Movement

A HIDDEN TRADITION

Downward dog, child’s pose, warriors one, two, and three. Once a complete unknown, yoga has become so widespread in the West that you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who hasn’t heard of it, and maybe even tried folding themselves, pretzel-like, into its positions at their local studio. In fact, downward dog and its ilk are so popular here that they’ve become almost synonymous with the word yoga.

In reality, these well-known poses come from a particular yogic tradition called hatha yoga, first brought to the West starting in the late 1800s and picking up steam midway through the 1900s. What many understand as yoga itself is actually just one particular branch of a much bigger tree of yogic traditions.

Another one of these branches, although still practiced to this day, is far less known in the West—trulkhor, or “magical movement,” the yogic practices of Tibet. For a thousand years, Tibetan yoga has been part of Tibetan Buddhist spiritual training, used primarily to enhance meditation by clearing away mental and physical obstacles like anger or drowsiness. There are many kinds of magical movement practices in the different Tibetan traditions. All of the main traditions of Tibetan religion practice some kind of trulkhor, although it is most prevalent in the Kagyu and Nyingma schools of Buddhism as well as in Bön. I am blessed to have been practicing magical movements, first with the Nyingma and then with the Bön lineage, for almost thirty years.

The existence of Tibetan yoga may surprise even those familiar with Tibetan Bön and Buddhism, since Tibetan teachings in the West, until very recently, focused more on various mind-based practices such as concentration and visualization. For a long time, this lack of information gave magical movement an aura of secrecy or mysticism about it. Nowadays, though, magical movement is slowly being taught all over the world, and its instructional texts are being translated into English and other languages.

Yoga was one of the many spiritual practices that arose during the pan-Asian tantric movement, which began around the fourth century BCE and reached its apogee four hundred years later. Its wellspring may have been India, but it spread across Asia, mixing with local religious tradition and culture. While the exact history of the Tibetan tradition of magical movement has yet to be written, contemporary religious leaders and scholars date it back to at least the eighth century CE. Some even claim that different forms of it were practiced much earlier and preserved as an oral/aural tradition. Its existence can be definitively established by the eleventh century CE, so we can easily state that it has been practiced for at least a thousand years.

WHY PRACTICE TIBETAN YOGA?

Although nowadays yoga is often understood as exercises that promote physical and mental health, at its core the purpose of all yoga is liberation—enlightenment—and traditionally defined, yogic practices are ones that make the body the locus and the tool for reaching enlightenment. So, like all traditional forms of yoga, enlightenment is the purpose of magical movement as well. In the Tibetan viewpoint it is a technique for enhancing meditation by getting rid of the mental and physical obstacles that block access to meditative states of mind. And, like many forms of yoga, it comes with its own wonderful nomenclature that reflect its culture of origin, meaning that if you follow this book’s instructions, you may soon find yourself “striking the athlete’s hammer” or moving as a “wild yak butting sideways.”

For those less spiritually inclined, practicing magical movement also comes with a host of practical benefits. Traditionally, Tibetan yogis and accomplished meditators living in solitude in caves used it to help dispel all kinds of physical and mental illness. With no access to hospitals or any healthcare professionals, it was one of their only options for restoring good health, and by their accounts it served them well—so well that scientists have begun studying magical movement’s health benefits, in particular for cancer patients, in randomized controlled trials. These benefits include stress reduction, the elimination of intrusive thoughts, and better sleep.

At this point, you may be wondering why I am specifically referring to Tibetan yoga as “magical movement.” Why is it not simply called Tibetan yoga, the way that we say “hatha yoga” or refer to the well-known Tibetan devotional practice as “guru yoga”? The term used in the Tibetan texts, trulkhor, is a compound comprised of trul and khor. Trul is usually translated as “magic” or “magical.” It can also take on the meaning of “machine” or “mechanics” when combined with khor, which literally means “wheel,” but it can also be translated as “circular movement” or just “movement.” Through many conversations with Ponlob Thinley Nyima, the current principal teacher at Menri Monastery in India and a magical movement master, we’ve settled together on “magical movement” as a translation, because of the magic-like experiences practicing this yoga generates.

I don’t mean “magic” in the way that we usually understand it in the West, which might conjure images of wizards and wands. In Asian disciplines, magic has less to do with spells and charms and more to do with inner states of transformation. Lao Tzu, the writer of the Dao De Jing, wrote about practices that use the body to alter the mind: “It is internal transformation at the deepest level that becomes the most sought after religious experience. It is also a transformation often linked to magic.”

This is the sense in which I am using the word magic. The magic that magical movement creates is inner transformation—inner magic. Tibetan yoga has the power to change the experience of the practitioner and their state of mind. In the old Tibetan texts, this could even mean the production of mystical experiences, like being able to walk without touching the ground or reversing the practitioner’s age. Magical movement’s healing properties, and its traditional consideration as medicine, can also be seen as “magical” in this way.

Or as Khenpo Tenpa Yungdrung, current abbot of Triten Norbutse Monastery in Nepal, says, the magic in “magical movement” refers to the “unusual effects that these movements produce in the experience of the practitioner.” This is the magic of magical movement, and it’s accessible to us all.

HOW THE MAGIC WORKS

The Body-Breath-Mind Triad

Magical movement, like all yogas, is a “mind-body” practice, because it entails an understanding of the mind-body connection. This setup is different than the Western conception that often separates mind and body. In the yogic and Tibetan view, our mind is located in our body and affected by it, and vice-versa.

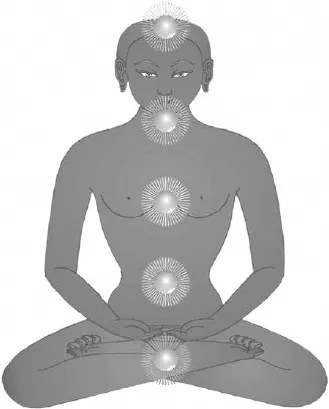

While Westerners often see the body as nothing more than its physical form—arms, legs, torso, and so on, with a subdermal system of interior organs and other physical networks—the Tibetan configuration conceives the body as a multi-layered dimension with components beyond just the physical ones. These invisible but experiential dimensions are sometimes referred to as the sacred anatomy or “subtle body.” This subtle body is composed of a complex network of channels together with the winds that run within those channels. The subtle consciousness—our mind—rides through the body on these vital winds. The subtle body can thus be understood as the landscape where the mind and the physical body connect with each other. You are probably already familiar with the term chakras, which are the major junctures of these channels, places where immense vitality is gathered and also where obstructions to the vital winds occur.

The five chakras of our subtle body

In Tibetan spiritual traditions, body, energy (in this case breath-energy or wind), and mind are the three doors to enlightenment, meaning that they are the three loci of spiritual training. Magical movement integrates all three.

Among the thousands of meditative practices within the Tibetan traditions, while the three components of body, breath, and mind are always there, particular practices emphasize one over the others. The sitting meditation practices you’re likely familiar with, for instance, in which the practitioner sits cross-legged in the lotus position, are a common method of emphasizing the mind over the body or breath. Of course, in the standard lotus pose for meditation the mind is supported by an unmoving body, and the breath is flowing naturally; the body and breath are involved, but are not being used as anything more than supports. But there are also many Tibetan practices that emphasize the body, like bowing or prostrations, circumambulation, pilgrimages, and of course, the yogic practices.

Different yogic traditions, while they all utilize the body as an aid for reaching enlightenment, have different techniques. In some Indian styles of yoga, the practitioner aims to hold a pose (asana), with the body unmoving and the breath flowing naturally. By keeping still in a specific body posture, the mind will stop and be stable. In other words, by controlling your body you control your mind.

In magical movement the practitioner actually holds the breath using a certain method—we’ll get into this below—while the body moves. And in the particular magical movement lineage that we will be learning in this book, at the end of the movement the breath is released in a particular way, opening the possibility to reconnect to one’s natural mind state. In magical movement the body and breath are not mere supports for a mind-focused practice, but are the main focus themselves. In this way magical movement is similar to Chinese mind-body practices such as tai chi and qigong, which share with Tibetan yoga the aspect of developing focused attention through movement. In contrast to magical movement, though, in tai chi and qigong the breath is not held but rather maintained as naturally as possible, more like in Indian yogas.

We’ll get more into the specifics as we go on, but for now, remember that magical movement brings a different conception of the body to the foreground, that of the internal landscapes of the sacred anatomy or subtle body and its dynamics. This subtle body is the place of all yogic training, including magical movement, which integrates the body, the breath, and the mind on the way to liberation.

Clearing Away Obstacles

It is also at the level of the subtle body that magical movement works its magic, so to speak—the removal of physical and mental obstacles that are blocking desired mental states. This is a common feature in Tibetan yogic traditions. In Tibetan, the term used is geksel, literally “clearing (sel) away the obstacles (gek).” In simpler language, the great Bön teacher Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak says that magical movement should be used when one’s meditation state is unclear, unstable, or weakened in some way, because magical movement will clear out whatever is causing the issue and help one to reconnect to the natural state of mind. You can think of it like a reboot that sweeps away any bugs in the system.

Ponlob Thinley Nyima believes that each magical movement technique was created when a practitioner needed to overcome an obstacle to meditation and found through experience that a particular movement helped. So, specific magical movements tackle specific things. For example, “rolling the four limbs like wheels” is helpful for overcoming pride; “waving the silk tassel upward” helps overcome jealousy; and “stance of a tigress’s leap” overcomes drowsiness and agitation. There are also sets that focus on specific areas of the body.

Obstacles are removed in the landscape of the subtle body—the channels it’s composed of, the breath currents or winds that run through those channels, and the mind that rides on that breath. Magical movement is based on what is known as tsalung, the practices of the channels (tsa) and winds (lung). In these, the practitioner becomes familiar with the channels of the subtle body first through visualization and then by using the mind to direct the breath and winds along those channels. In this way, the wind is made to circulate through the channels more evenly in terms of the rhythm of the inhalation and exhalation, and with a greater balance in terms of the amount and strength of the winds through the different channels.

The mind rides on the wind, like a rider on a horse, and the two travel together through the pathways of the channels. As the wind circulating in the channels becomes more even and balanced, the channels turn increasingly pliable, allowing the winds to find their own comfortably smooth rhythm. When the wind rhythm is smooth, like a wave, the mind riding on it has a smoother ride, too, which reduces agitation.

With the help of movements that guide the mind and the winds into different areas of the body, magical movement brings forth the possibility of healing or harmonizing the entire body-energy-mind system. This kind of harmony is a short-term goal of all yogic practices (the ultimate goal, remember, is enlightenment) and is also a model of good health that is in line with the concept of well-being in Tibetan medicine. In magical movement in particular, the releasing of specific obstacles using specific movements allows the winds to flow better throughout. Rather than a “tin man,” whose being is obstructed by various broken-down parts, your whole ecosystem of body, br...