![]()

CHAPTER 1

Equal Protection of the Law: Criminal Justice or Injustice?

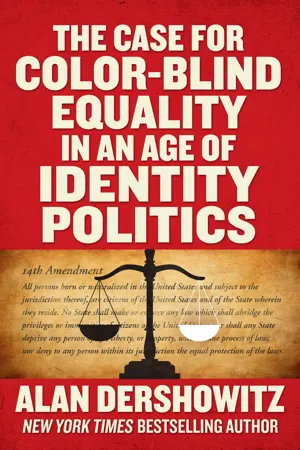

The Fourteenth Amendment promises every citizen “the equal protection of the law.” For many citizens, especially those of color, this has been a broken promise. Jim Crow laws, lynchings, overt discrimination, police abuse, and systemic racism were the rule, rather than the exception, especially but not exclusively in the South for a century following the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment. Matters began to improve, first as a matter of law and only later as a matter of practice, following World War II.

One area in which progress has been halting at best has been encounters between police and minority citizens. This explosive issue came to a dramatic head with a slew of killings captured on cell-phone cameras, the establishment of the Black Lives Matter movement, and, most recently, the gruesome death of George Floyd at the hands of Derek Chauvin.

I wrote a series of op-eds about the Chauvin and related cases that reflect my nuanced and often-controversial views about the events surrounding the death, the trial, and the conviction. I present them here in roughly chronological order:

Thank Goodness for Cell-Phone Cameras

I just finished watching the god-awful video of former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin keeping his knee on the neck of the dying George Floyd for more than nine minutes.

It is among the most powerful pieces of evidence I have ever seen—it indisputably shows Chauvin keeping his knee on Floyd’s neck and/or shoulder as Floyd submissively lies on the ground, hand-cuffed, telling Chauvin he can’t breathe and calling for his mother. Numerous observers at the scene keep demanding that Chauvin get his knee off Floyd’s neck as Floyd clearly slips into unconsciousness. Floyd does not resist or fight back. He simply struggles to breathe.

There is no conceivable reason why Chauvin had to keep his knee on Floyd’s neck. Floyd posed absolutely no danger— certainly not after the first couple of minutes of complete submission. Chauvin was warned by bystanders that he was killing Floyd and that Floyd was unable to breathe. They begged him to get his knee off Floyd’s neck. Some bystanders tried to get closer to Floyd, but other police officers stood in the way and stopped them. The evidence of Chauvin’s moral culpability is overwhelming and beyond dispute. He deserves no pity or compassion. But he does deserve justice. And so do we.

Chauvin’s legal guilt poses an entirely different series of questions: Did he intend to kill Floyd? Did he realize that death could have resulted from keeping his knee on Floyd’s neck? Was he reckless in not removing his knee? Would Floyd have died from Chauvin’s knee if Floyd did not have drugs in his system or a heart condition?

These and other questions will have to be decided by jurors after hearing all of the evidence and arguments and being instructed by the trial judge. But the moral, political and ideological issues seem Black-and-white: no police officer should ever do what Chauvin did to a man who was subdued, was lying on the ground, was unarmed and was surrounded by five armed officers. The tape, without anything more, compels that conclusion. If the Minneapolis police guidelines allow such conduct, they must be changed. The video speaks louder than any effort to justify Chauvin’s actions.

Now let us imagine how different the situation would be if there had been no cell-phone videos—if it had been the word of the police officers against those of the largely Black bystanders. Many such cases have occurred over the past several years. Some have been videotaped, others not. The videotape in this case, and in others, has made all the difference.

As a civil libertarian, I realize that the pervasiveness of cell-phone cameras is sometimes a double-edged sword. On the positive side, it documents police abuses and other evils that would otherwise be difficult to prove. On the negative side, the pervasiveness of these cameras threatens all of our privacy if used promiscuously and without consent or knowledge.

In one sense, it’s meaningless to debate the pros and cons of any new technology because no matter what we say, the technology will advance, improve, and become part of our lives. The law can do something, but not much, to control its misuse. We must acknowledge that with every technological innovation, we lose a little bit of privacy, autonomy, and dignity. (Just ask Jeffrey Toobin!)

The bottom line is that we must learn to live with the new technology. The law will always be playing catchup, but will never succeed in actually catching up with advancing technology.

The Chauvin case demonstrates the positive use of cell-phone video cameras. The video of Chauvin refusing to lift his knee off the neck of the dying Floyd has changed the world. It will never be the same. And it should never be the same. What we see on that video is a vision of hell that cannot be allowed to become or remain the new normal, the old normal, or any version of normal. So two cheers for video cameras.

Can Derek Chauvin Get a Fair Trial for the Killing of George Floyd?

The trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin is about to begin. It will be televised and promises to be one of the most watched trials since that of OJ Simpson.

The death of George Floyd is among the most consequential events of the twenty-first century. The image of Chauvin with his knee on Floyd’s neck has traveled around the world and influenced hundreds of millions of people to seek racial justice.

Several important questions arise: Can Chauvin get a fair trial in the current atmosphere? Can jurors be expected to ignore the potential for violence if they fail to convict? Has the attorney general properly charged Chauvin, or has he overcharged him for political or ideological reasons? Did Chauvin’s actions “cause” Floyd’s death, or was it caused by his drug use or other medical factors?

Floyd’s lawyer has declared, “This will be a referendum on whether police are held accountable for killing Black people in America.” But trials are not referenda on macro issues of social justice. They should deal solely with the micro issue of whether a particular defendant is guilty of the charged crimes. If a prosecutor were to use the word “referendum” in his arguments, the judge would have to declare a mistrial. To the contrary, the judge must instruct the jury that jurors must ignore all outside pressures, concerns, or “facts” they may have learned from the media.

I have no brief for Derek Chauvin. What I saw on the video was inexcusable, warranting his firing and an investigation into possible criminal conduct. But I do have a brief for the fair application of law to every defendant, even those whose conduct I abhor.

The first issue is whether the trial should have been postponed and moved out of Minneapolis, which recently made a publicized mega-million-dollar settlement with the Floyd family. Some jurors may interpret that settlement as an admission of fault or guilt on the part of its employee.

Even more concerning is the likelihood that some jurors may fear that if they vote against a murder conviction, there may be violent reactions in their neighborhoods or even against them. The fact that the names of the jurors are being kept secret may reinforce that fear.

These factors should have counseled postponing and moving the trial to a rural area, with jurors who are less fearful of the consequences of an unpopular verdict.

This brings us to the issue of whether Chauvin has been properly charged. The most serious count is murder in the second degree, which requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt that Chauvin caused the death of Floyd “with intent to effect [his] death.” There is no evidence that would prove that Chauvin intended to kill Floyd. Second-degree murder also applies to unintended killings that occur during a “drive-by shooting,” during the commission of a separate and independent felony, such as bank robbery, or “while intentionally inflicting . . . harm, on a victim who was protected by a formal restraining order.” None of these elements seem present in the Chauvin situation. If that is true, the charge of second-degree murder would be improper.

That may be why the prosecutor recently added a charge of third-degree murder, which is defined as follows: “whoever, without the intent to effect the death of any person, causes the death of another, by perpetrating an act imminently dangerous to others . . .” (emphasis added). There are two plausible readings of that statute: one suggests that it applies only when the act is dangerous, not only to the person who was killed, but to “others,” meaning people in addition to the actual victim. This was true in the Breonna Taylor case, where the police shot into a darkened room, killing Taylor and endangering the lives of the people in the adjoining apartment. Under this reading, the statute would not apply to placing a knee on the neck of an individual—which poses only a danger to the victim and not to “others.” The other plausible reading is that the word “others” applies to anyone other than the defendant. That is the reading accepted by a recent appellate-court decision that is now on appeal.

Regardless of how the Minnesota courts resolve this ambiguity, the US constitution requires that a defendant be given fair warning at the time he commits an alleged crime that his act constitutes that crime under the clear language of the statute.

If the third-degree murder statute is reasonably subject to two interpretations, the law requires that ambiguities in it must be resolved in favor of the defendant. This is especially the case when another homicide statute leaves no ambiguity about its clear application to the facts. That is the situation in the Chauvin case.

Here are the words of the manslaughter in the second-degree statute: “A person who causes the death of another . . . by the person’s culpable negligence whereby the person creates an unreasonable risk, and consciously takes chances of causing death . . .” This statute is so close to what is alleged against Chauvin that it is as if it were drafted specifically to cover this case.

There are two principles that require that Chauvin be charged only with manslaughter in the second degree and not with murder in the second or third degree. The first is that when there are multiple statutes that arguably cover an alleged crime, the state should charge the one that most closely fits the facts of the case. This is because the legislature, by enacting the closest statute, plainly intended it to apply to the conduct at issue. That widely accepted principle of statutory construction should be applied in criminal cases.

Related to that rule is the principle of “lenity,” with deep roots in our legal system. It requires that when there are equally plausible interpretations of criminal statutes, the courts must apply the one that is most protective of the defendant. Minnesota’s statutes do not give rise to equally reasonable interpretations. The one that favors the defendant is more reasonable: it would require applying the manslaughter and not the murder statute to Chauvin’s conduct.

If this were an ordinary case, it would be much easier for a prosecutor simply to charge manslaughter. But there are understandable pressures on this prosecutor to include murder among the charges, because so many people believe that Chauvin murdered Floyd. However understandable the reasons may be, overcharging Chauvin would be unfair. Political, ideological, and “racial justice” concerns have no proper place in a criminal courtroom.

Finally, there is the issue of whether Chauvin’s acts caused Floyd’s death. Homicide statutes require proof of causation. This is a complex issue of science, law, and morality.

The defense will argue that the knee-on-neck method of subduing a suspect is consistent with Minneapolis police protocol and that none of the many other suspects to which it was applied have died. Therefore, Chauvin’s use of the protocol could not have caused this death: it resulted from other factors that were not present in the cases where the protocol was used without causing death.

The prosecution will argue that if Chauvin had not kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes, he would still be alive.

Each side has a point, and a lot will turn on the judge’s instruction. If he tells the jury that the defendant’s act must be the “but for” cause of death, the prosecution will win (despite the fact that there may have been other “but for” causes). If he instructs that the act must be the major cause, a substantial cause, or the proximate cause, the defense may prevail or a hung jury may result. This may look like an open-and-shut case morally and politically, because it is so clear in retrospect that Chauvin should never have kept his knee on Floyd’s neck. But it is far from an open-and-shut case legally. So stay tuned and wait for the evidence, arguments, and instructions. It’s good that the trial is being televised so that viewers can see for themselves how complex the legal issues may turn out to be.

Deconstructing the Floyd Videotape: Does It Prove Chauvin’s Guilt?

In his opening argument for the state, prosecutor Jerry Blackwell featured the entire nine-minute cell-phone video of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin keeping George Floyd subdued even after he was unconscious and probably dead. It was the most damning piece of evidence since the video in the Rodney King case back 1991. No reasonable person watching that video could justify what Chauvin did—certainly not during the final several minutes, when it was clear that Floyd was incapable of offering resistance and was crying for his mother and saying he couldn’t breathe. No one watching that hellish video will ever forget it. Based on the video alone, Chauvin deserved to be fired, as did the police officers who stood by and did nothing to prevent Floyd’s unnecessary death.

But the trial being conducted in the Minneapolis courtroom is not about morality, politics, or even ultimate justice. It is only about whether the state can prove beyond a reasonable doubt all the elements of second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter—the charges that will be presented to the jury.

The videotape will be the most important piece of evidence, as the prosecutor reminded jurors when he asked them to judge what they saw with their own eyes. But the defense will ask the jury to consider facts beyond the videotape: what happened before the video began, what happened during the video but outside of its view, and what happened after the video ended. They will also offer a somewhat different interpretation of what is on the video itself.

The defense will try to show that when first arrested, Floyd did try to resist, did swallow an illegal drug to prevent the police from seizing it, and did refuse to follow the orders of police officers. They will also prove that Floyd shouted that he could not breathe well before Chauvin pinned him to the ground. The defense will claim that because of his unvideoed acts, the officers were justified in handcuffing Floyd and placing him on his stomach and on the ground.

The defense will also claim that before and during the period shown on the video, an angry crowd was beginning to gather to protest what the police were doing to Floyd. They will also argue that the protests generated fear in the minds of the police officers, including Chauvin, and distracted them from focusing on the impact of Chauvin’s knee on Floyd’s neck. They also dispute the prosecution’s claim that the video conclusively demonstrates that Chauvin had his knee on Floyd’s neck, thus obstructing his breathing. They will argue that a closer look at the video suggests that Chauvin’s knees were on Floyd’s shoulders and that there was no obstruction of his breathing.

The defense will also focus on the presence of large quantities of life-threatening drugs in Floyd’s body, coupled with preexisting medical conditions that may have contributed to his demise.

For the prosecution, this case is all about the video, as well it should be, because of the power of putting the jurors at the scene and encou...