- 364 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

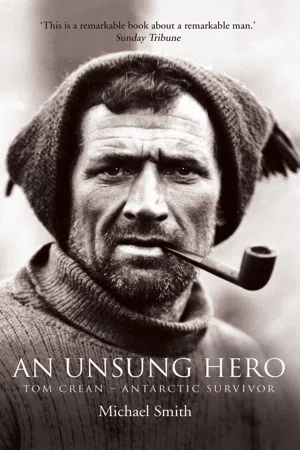

An Unsung Hero

About this book

The story of the remarkable Tom Crean who ran away to sea aged 15 and played a memorable role in Antarctic exploration. He spent more time in the unexplored Antarctic than Scott or Shackleton, and outlived both. Among the last to see Scott alive, Crean was in the search party that found the frozen body. An unforgettable story of triumph over unparalleled hardship and deprivation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Unsung Hero by Michael Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A farmer’s lad

Thomas Crean was born on 20 July 1877 at Gurtuchrane, a remote farming area a short distance to the west of the village of Anascaul on the Dingle Peninsula, in Ireland’s County Kerry. The area is, even today, a quiet unassuming mixture of houses and farms surrounded by rolling green hills.

The contrast with the hostile, frozen Antarctic Continent where Crean would carve a remarkable career could hardly be more stark. By odd coincidence, Crean would later share his birthday with Edmund Hillary, the first conqueror of Mount Everest, renowned Antarctic traveller and one of the great adventurers of the twentieth century.

The Dingle Peninsula is rich in tradition, its origins easily traced back to the earliest European civilisations. It became a centre of Early Christian activity and despite conquest by both the Anglo-Normans and English, the area survived centuries of political and religious repression and persecution. The people were tough, resolute survivors and it is little surprise that Kerry was one of the areas which fought hardest to preserve the Irish language. To this day, the Dingle Peninsula is a Fíor-Gaeltacht, an Irish-speaking region.

By the late nineteenth century, it was in common use along the Peninsula and Crean’s parents were part of the last generation of Kerry people who spoke Irish as a first language. As a young man, Crean was brought up speaking both Irish and English.

He was a member of a typically large Irish rural family which, like so many of the time, struggled against grinding poverty and the persistent fear of crop failure and famine. The name Crean is fairly common in the Kerry region and is thought to be derived from Curran. In Irish his name is written as Tomás ó Croidheáin or Ó Cuirín.

His parents, Patrick Crean and Catherine Courtney, were farmers at Gurtuchrane who produced ten children during the 1860s and 1870s. Hardship was a way of life, with few if any luxuries and little prospect of any escape from the unrelenting battle to make ends meet and keep stomachs filled.

At the time of Crean’s birth, Ireland itself was still recovering from the devastating effects of the Great Famine three decades earlier when between 800,000 and 1,000,000 people perished – one in eight of the total population at the time – after the disastrous failure of the potato crop. It was to have a searing effect on Ireland’s soul, encouraging the mass emigration of perhaps two million people in the years immediately afterwards and greatly reinforcing the belief that Ireland should be master of its own affairs.

But by the end of the 1870s, famine once again threatened Ireland and inevitably reawakened in many fears of a repeat of the appalling horrors. The year of Crean’s birth, 1877, was miserably wet in Ireland, which set off an unfortunate chain of events that led to a deterioration in the potato crop in the following years. At the same time, the collapse of grain prices meant many farmers were caught in a catastrophic poverty trap and were unable to afford the often exorbitant rents imposed by the hated absentee landlords. For many farmers, especially in the west of Ireland, the terror of famine was now matched by the fear that they might be evicted from their land and homes. These people would have known precisely what another Irishman, George Bernard Shaw, meant 30 years later when he wrote that poverty was the greatest of evils and worst of crimes.

It was against this background of impending famine, dwindling income and a growing family, that Patrick and Catherine Crean struggled to provide a life for Tom and his five brothers and four sisters; an environment which inevitably helped shape and prepare the youngster for the hardships and privations which he would face during his lengthy spells in the Antarctic.

Tom was given a very basic education at the nearby Brackluin School, Anascaul – the local Catholic school – and like most youngsters of the age, probably left as quickly as possible. It was not uncommon for children to leave school at the age of twelve, although the majority stayed on until they were fourteen. Either way, the youngsters were given only a rudimentary education which provided them with little more than the ability to read and write. The need to help on the farm and bring in some meagre amounts of money to the family was overwhelming.

It is likely that events down the hill in the nearby village of Anascaul provided young Tom with his first taste for travel and adventure.

The village sits at the junction of a main road through the Dingle Peninsula and the Anascaul River, which flows down from the surrounding hills. It is a natural meeting place for travellers.

For centuries Anascaul had been the site of regular local fairs. In his book, The Dingle Peninsula, local author, Steve MacDonogh, said that for many centuries the Anascaul fairs were a ‘vital focus’ for the area. He recalled that the Anglo-Normans, who had established many commercial fairs across Ireland, settled around the Anascaul area in significant numbers. Tralee, one of Kerry’s main towns, is known to have been established by the Anglo-Normans in the thirteenth century. Nearby villages, Ballynahunt and Flemingstown, are also said to be associated with the early Anglo-Norman presence.

Young Tom Crean grew up in this poor, rural community and must have drawn some relief from these regular fairs which punctuated the otherwise dreary routine. Anascaul played host to fourteen separate fairs a year, attracting a rich variety of locals and outsiders. The biggest occasions were the twice-yearly horse fairs in May and October, one of the oldest events in Ireland’s long tradition of horse-trading and which attracted people from all corners of the land.

But the most regular event at Anascaul was the monthly fair, which cobbled together an unlikely mixture of commerce and trade and fun and entertainment. The entertainment, said MacDonogh, was not mere frills on a mainly commercial occasion but, in true Gaelic spirit, was essential to the proceedings. MacDonogh described a typical scene:

‘The wheel of fortune, stalls selling humbugs, women in their best dresses and hats, men whose clothes echoed time spent in foreign parts, the three-card trickster, ballad singers, fiddlers, match-makers, peddlers and beggars – all combined to make a colourful social gathering as well as an occasion for business.’1

It was in the pubs and on the street corners that stories were told and in typical loquacious Irish fashion events were relived and the imagination of a young farmer’s son was allowed to run wild. Against a harsh impoverished background of farm life, the tales of faraway places would have sounded all the more attractive to an inquisitive young man. The urge to travel must have been all too powerful.

Several of Tom’s brothers emigrated from Kerry around this period and MacDonogh also notes that for some time there had been a tradition of Anascaul’s sons moving away to serve in the British navy.

Tom’s elder brother Martin found work across the Atlantic on the burgeoning Canadian Pacific Railway. Michael went to sea and was lost with his ship. Cornelius, who was six years older than Tom, grew up to become a policeman in the Royal Irish Constabulary and was later murdered during ‘The Troubles’. Tom’s sister, Catherine, also married a policeman. Two other brothers, Hugh and Daniel, remained behind to maintain the family tradition on the land. When their father Patrick died, Hugh and Daniel split the family farm in two and remained at Gurtuchrane for the rest of their lives.

Growing up on the farm in the 1880s and 1890s was a huge challenge. It needed a strong sense of survival to co-exist in a home environment where the ten Crean children scrapped for supremacy and their parents’ attention. Patrick Crean struggled to make ends meet and had little time to provide anything approaching today’s level of parental guidance.

It was a severe upbringing which inevitably left the young Crean with a strong streak of independence. It was this independence which prompted the youngster to flee the family nest at the earliest opportunity.

It was customary at the time for the British navy to send its recruiting officers out to Irish villages to find new able-bodied men for the service. The navy was always on the lookout for fresh blood and the offer to swap the uncompromising life on the land for the apparent romance of the sea was a permanent feature of life in the area. Many young Irishmen were easily persuaded to sign up. At the time, the British navy boasted the world’s most powerful fleet and its prestige was second to none. To young men like Tom Crean, the opportunity to escape from the bleak hardship of daily life must have been irresistible. The alternative of maintaining the unrelenting struggle was easily dismissed, and it is no surprise that Tom Crean left home when he did.

The background to his departure is far from clear, although it appears that Tom had a major row with his father when he inadvertently allowed some cattle to stray into the potato field and devour the precious crop. In the heat of the moment, Tom swore he would run away to sea.

Crean, still a fresh-faced fifteen years old, set off for Minard Inlet, a few miles southwest from Anascaul where there was a Royal Navy station. Crean and another local lad called Kennedy approached the recruiting officer and, suitably impressed by his patter, blithely agreed to join Queen Victoria’s mighty Navy.

Although Crean was a fiercely independent young man, he was still unsure about the reception he might receive at home and did not immediately tell his parents about his new life. He chose not to inform them until after he signed the recruitment papers, which meant there was no chance of persuading him to stay on the farm. It was also an early indication of Crean’s self-confidence and determination. And, if the two youngsters were looking for extra courage, they probably found it in each other’s company.

But, after deciding to enlist, Crean had another problem. He was penniless and did not even possess a decent set of clothes to wear for the trip to a new life. He promptly borrowed a small sum of money from an unknown benefactor and persuaded someone else to lend him a suit. Tom Crean took off his well-worn working clothes in July 1893, squeezed into his borrowed suit and left the farm, never to return.

As he strode off, the young man had precious few possessions to carry with him as a reminder of his home and upbringing. But Crean did remember to put around his neck a scapular, a small symbol of his Catholic faith and a token souvenir of his roots. The scapular, which is two pieces of cloth about two and a half by two inches attached to a leather neck cord, contains a special prayer that offers particular spiritual relief to the wearer. As he set off into the unknown for the first time, Crean will have drawn special comfort from its fundamental tenet – that the wearer of the scapular will not suffer eternal fire. It was to remain around his neck for the rest of his life.

He travelled down to Queenstown (today called Cobh), near Cork on Ireland’s southern coast with James Ashe, another Irish seaman from the merchant navy. Ashe was a close relative of Thomas Ashe from nearby Kinard, who was to become a leader of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and achieve martyrdom in 1917 by dying on hunger strike in Mountjoy Prison at the height of the war with the British.

Tom Crean was formally enlisted in the Royal Navy on 10 July 1893, just ten days before his sixteenth birthday.2 Officially the lowest enlistment age was sixteen and the assumption is that the fifteen-year-old lad either forged his papers or lied about his age before signing up.

At this formative stage in his life, young Tom was not the tall, imposing figure well known on the polar landscape in later life. According to Ministry of Defence records of the time, the farmer’s son, who had a mop of brown hair, stood only 5 ft 7¾ inches when he signed on the dotted line in July 1893 as Boy 2nd Class, service No 174699.3

His first appointment was to the boys’ training ship, HMS Impregnable at Devonport, Plymouth in the southwest of England, where he served his initial naval apprenticeship.4

Life in the navy was tough, particularly for a young man away from home for the first time in his life. Discipline was strict and the regime harsh and unsympathetic. His initiation into naval life was perhaps the first test of the strength of character which was to become a hallmark of his adventurous life.

He survived his first examination and promotion of sorts came fairly quickly for the young man. Within a year Crean had taken his first step upwards and was promoted to Boy 1st Class. A little later on 28 November 1894 the Boy 1st class was transferred to HMS Devastation, a coastguard vessel based at Devonport.5 Crean, for the first time, was at sea.

Little is known about Crean’s early career in the Navy. It was, however, punctuated with advancement and demotion and it may not have been an altogether happy time for the youngster as he came to terms with the new life a long way from home. Some reports suggest that at one stage Crean became so disenchanted with the naval routine that he tried to run away. One writer claimed that Crean was so dismayed by the poor food and rough accommodation on board naval ships of the time that he threatened to abscond.6

The regime in the late Victorian Navy of the time was undoubtedly arduous and unforgiving. While the Royal Navy was traditionally the right arm of the British Empire, by the late Victorian era it had become smugly complacent, inefficient and out of date. It had more in common with Nelson and still lent heavily on rigid discipline and blind obedience. It required sweeping reforms by the feared Admiral Sir John ‘Jackie’ Fisher to eventually modernise the navy in time for the First World War in 1914.

But there is a strange inconsistency about a young man, fresh from a poor, undernourished rural community in the Kerry hills complaining about the quality of the food and bedding. It may be that Crean, like others at the time, had other grievances. Or it may well have been a simple case of a young man a long way from his roots who was homesick. In any event, he drew some comfort from the other young Irish sailors around him and decided that he, too, would stick it out.

On his eighteenth birthday in 1895, after exactly two years service, Crean was promoted to the rank of ‘ordinary seaman’ while serving on HMS Royal Arthur, a flag-ship in the Pacific Fleet. A little less than a year later, he advanced to become Able Seaman Crean on HMS Wild Swan, a small 170-ft versatile utility vessel which also operated in Pacific waters.

By 1898, Crean was apparently eager to gain new skills and was appointed to the gunnery training ship, HMS Cambridge, at Devonport. Six months later, shortly before Christmas 1898, he moved across to the torpedo school ship of HMS Defiance, also at Devonport. At the major naval port of Chatham, he advanced a little further by securing q...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Notes

- Preface

- Chapter 1 - A Farmer’s Lad

- Chapter 2 - A Chance Meeting

- Chapter 3 - Into the Unknown

- Chapter 4 - A Home on the Ice

- Chapter 5 - Into the Wilderness

- Chapter 6 - South Again

- Chapter 7 - South in a Hurricane

- Chapter 8 - Hopes and Plans

- Chapter 9 - The Last Great Land Journey

- Chapter 10 - A Race for Life

- Chapter 11 - A Tragedy Foretold

- Chapter 12 - Fatal Choice

- Chapter 13 - A Grim Search

- Chapter 14 - A Hero Honoured

- Chapter 15 - The Ice Beckons

- Chapter 16 - Trapped

- Chapter 17 - Cast Adrift

- Chapter 18 - Launch the Boats!

- Chapter 19 - A Fragile Hold on Life

- Chapter 20 - An Epic Journey

- Chapter 21 - Crossing South Georgia

- Chapter 22 - Beyond Belief

- Chapter 23 - Return to Elephant Island

- Chapter 24 - Life and Death

- Chapter 25 - War, Honour, Marriage

- Chapter 26 - Tom the Pole

- Chapter 27 - Memories

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Dedication

- Copyright

- If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy the following eBooks