WAR CASTS A LONG SHADOW

‘We … therefore take this opportunity of asking you to vote for the deletion of the word “male” … and thereby establish once and for all the principle of woman suffrage.’

— Elisabeth Elmes, Munster Women’s Franchise League

There were heart-rending scenes on the quayside in Queenstown (Cobh), Co. Cork, in the late afternoon of 7 May 1915. A few hours earlier, at 2.10 p.m., a German submarine torpedoed the pride of the Cunard line, the Lusitania, eight miles off the Cork coast. It sank within eighteen minutes, killing 1,198 people and leaving the 761 survivors struggling to stay afloat while trawlers and tugs in the vicinity came to their aid. Ashore, people rushed to the water’s edge to see how they might help. Every minute more ‘sightseers filled with pity and profound sympathy’ arrived on the scene.1

The harrowing descriptions of the procession of barefoot, bewildered men, women and children who struggled ashore would provoke worldwide outrage, and increase the pressure on then-neutral America to join Britain and the Allies in the Great War. But on that afternoon in May the focus was on the human tragedy that was just unfolding. Eye-witnesses described the ‘fearful explosion’ that hit the starboard side of the luxury ocean liner with ‘terrible suddenness’ while many of the passengers were still having lunch. The vessel, which had been en route from New York to Liverpool, listed to one side, making it almost impossible to launch lifeboats in time to save lives.

By early evening, partially clothed men, women and children, their ‘strained features stamped with the fear of death’, were being helped onto the quayside in Queenstown in what contemporary accounts described as ‘poignant scenes that bled the heart’.2

An Irish Times reporter was struck by the efforts of local people, who rushed to help survivors from the fishing boats that had come to their assistance.

Willing helpers with their arms around their [the survivors’] bodies, assisted them to walk to the hotels, hatless and shoeless, scarcely able to toddle through injuries to their [l]egs, arms and bodies. They were in their sea-soaked apparel and in a sad plight. Many of them were unable to walk, and had to be removed on stretchers to their resting places in boarding houses and hotels, where they were comfortably housed and humanely treated, and given hot drinks to resuscitate their fatigued and shocked frames.3

Others told reporters of the outpouring of ‘great help, practical comfort and kindly sympathy’ extended to the victims. ‘Police, naval men, the military, and civilians all vied with each other to render succour to the distressed survivors, and to care for the many injured cases. All the hotels are converted into hospitals, and every other house is a home of mercy.’4 Local people came with hot drinks and food, and, between ‘great draughts of tea and mouthfuls of meat’, people enquired about their missing relatives. In the street there were women crying for their husbands or children, fathers hoping against hope that their loved ones had been saved, and orphans weeping disconsolately. Queues formed outside the makeshift morgues in the town market as survivors faced the horrifying prospect that their relatives might be among the dead.5

When news of the disaster spread to Cork, eighteen miles away, the lord mayor, Henry O’Shea, and the city coroner, John Horgan, went to visit the American consul at Queenstown, Wesley Frost, to reassure him that the citizens of Cork would render every service they could. Dr Winder, a solicitor and secretary of the Cork Branch of the Irish Automobile Association, telephoned all the car owners of Cork and organised a fleet of cars to transport the injured to hospitals in the city if necessary.

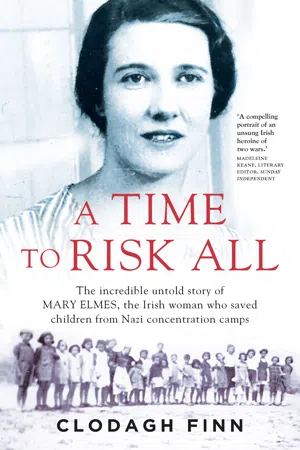

Two days earlier, Marie Elisabeth Jean Elmes turned seven at her home in Ballintemple in the suburbs of Cork. Although she had just started at Rochelle School on the Blackrock Road, the memory of what happened off the coast that year would stay with her for the rest of her life. The house had neither a telephone nor a motor car in 1915,6 but Mary’s father, Edward Elmes, a pharmacist, may have felt compelled to join others of his profession who were administering restoratives to the injured. In any event, the Elmes family travelled to Queenstown to join the thousands who had gathered there to pay their respects to the dead. What Mary Elmes saw that day made a lasting impression on her. She would later tell her children, Caroline and Patrick, that she met some of the survivors and that people in the streets were crying openly.7 Even ‘the most stoical could not look on the mournful happenings of the day unmoved,’ the Cork Examiner commented.

At 3 p.m. on Monday 10 May 1915 a solemn procession of hearses, private mourners, mounted police, clergy, corporation officials and military and naval officers filed through the town to bury more than 150 people in mass graves that had been dug by members of the Royal Irish Regiment at the Old Church graveyard on the outskirts of town. Some forty-five of those bodies were never identified, their coffins marked only with a number.

The following day, the Cork Examiner captured the sombre mood and grief felt by the thousands of ordinary people who lined the route to the cemetery.

It was an exceedingly sad procession, but an event which attracted the sympathetic interest of thousands of people from the City of Cork. Queenstown was in general mourning. All the shops were closed, and from one o’clock out people took every point of vantage to witness the dismal sight of the funeral proper of the victims. Only at the cemetery could one get an even approximate idea of the full meaning of the terrible tragedy … Three graves remained open … In these were all the horrors of the calamity mirrored. One of them contained 65 coffins and a total of 67 bodies – two babies had been interred with their mothers. The next yawned its full length, breadth and depth, and so also with the third grave of the Catholics … It was all too ghastly to comprehend and too sickly to dwell on.8

For weeks afterwards, the press reported on the disaster, chronicling the political repercussions (later, there were reports of a second explosion) and the growing list of casualties. It was clear by now that the Irish art collector Hugh Lane had gone down with the ship, as had the wealthy American magnate Alfred G. Vanderbilt. He was one of many prominent passengers who had received a telegram advising them not to travel on the Lusitania before it left New York. The Imperial German embassy had also taken out advertisements in the American press to warn passengers that ships bearing the British flag were in danger of coming under attack in British waters. Vanderbilt was not alone in ignoring the warnings. When the torpedo struck, he is said to have been calm and unperturbed. ‘In my eyes he cut the figure of a gentleman waiting unconcernedly for a train,’ resident artist at Covent Garden, Oliver P. Bernard, told the Cork Examiner. ‘The last that was seen of him, he was giving a lady passenger his lifebelt.’9

Germany stood firm. While it apologised for any American deaths, it claimed the ship was a legitimate target, as it had on board arms and ammunition destined for British soldiers. Controversy would rage over that point for a century afterwards. At the time, though, Britain and its allies felt entirely justified in condemning the attack. On 10 May 1915 the Irish Independent said in its editorial: ‘The whole civilised world shudders at the black deed and a cry for vengeance has gone up.’ It went on to say that the ‘foul and ghoulish crime’ was exactly the same in character as if ‘a band of assassins had suddenly swooped down upon the town of Cavan and in a few minutes murdered every single one of its inhabitants’.10

In the immediate aftermath, there were daily reminders of what had happened. For months, bodies were washed up along the coast of Co. Cork, keeping the disaster in the forefront of public consciousness and bringing the war closer to home. The people of Cork were already accustomed to seeing wounded soldiers being brought into the city, where they were treated in military and civilian hospitals. In December 1915 Mary Elmes made her own personal contribution to the war effort: she knitted pairs of socks and sent them to the soldiers fighting on the front. She included a pair for a senior British officer, Field-Marshal John French, apparently a birthday present. It’s possible that he was a family acquaintance. Months later, in August 1916, he wrote her a personal note of thanks. It read: ‘My dear Miss Marie, many, many thanks for your kind thoughts … on my birthday. I shall always keep and prize your present, Your … grateful friend, French.’ The framed letter, a treasured possession, is still in the family archives.11

The suffering Mary Elmes witnessed after the sinking of the Lusitania may have partly influenced her decision two decades later to join the Spanish Civil War relief effort. Even if it did not, when she sailed from London for Gibraltar in 1937 she had some inkling of what awaited her, because she had already seen the effect of war at first hand.

Marie Elisabeth Jean Elmes was born on Tuesday 5 May 1908 on the first floor of the family home, Culgreine, 120 Blackrock Road, Ballintemple, Cork. She came into the world in an airy upstairs bedroom that had one large window overlooking the tree-lined front garden and a second giving onto the back garden, with its greenhouse, pond, rockery and well-planted flower and vegetable beds.12 It was a wet day in late spring and there was some mist, but the temperature was moderate for May.13

The newspapers were already looking towards summer: in the Munster Arcade, in the city centre, ‘the latest ideas in summer millinery were particularly charming’. Charles Frohman’s Leah Kleschna was running at the Opera House, a five-act drama about a master jewel thief who raised his daughter to follow in his footsteps. In the council chamber of City Hall, the Cork Branch of the Women’s National Health Association was hosting a late-afternoon lecture on the home treatment of consumption (TB). A ticket on the ferry from Cork to Fishguard cost 15 shillings (one way, with cabin) and a night at the Clarence Hotel in Dublin (including breakfast) cost 4 shillings. If money was tight, several moneylenders were advertising their services on the front page of the Cork Examiner. On the news pages inside, the paper published an encouraging report about an ‘astounding decrease’ in emigration.14 The previous year nearly 40,000 Irish emigrants had left for America, but the figure in 1908 was not expected to exceed 15,000.

That was good news for Cork, a busy port city with a population of some 75,000 people. Marie’s father, Edward Elmes, was a pharmacist in the commercial heart of the city, working in the business founded by his wife’s family. J. Waters and Sons was a large dispensing chemist’s shop in Winthrop Street, but it also manufactured picture frames and supplied glass. Plate, sheet or mirror glass ‘could be supplied at the shortest notice’, customers were promised in a contemporary advertisement.15 Edward Elmes, who was originally from Waterford, had been in the city from at least 1901. The census of that year lists him as lodging at Pope’s Quay in the city centre. Pharmacy, like dentistry and veterinary medicine, was an occupation that had recently gained a new respectability: these were no longer apprenticeships but certified professions.16

This can only have been in Edward Elmes’s favour, because on 11 September 1906 he married his employer’s fourth and youngest daughter, Elisabeth Octavia Waters, at St Luke’s Church in a service conducted by the bride’s older brother, Rev. Richard Waters. At the time, 8½ per cent of the city’s residents belonged to the Church of Ireland and many of them retained significant commercial and political power.17 The newly married couple were among the well-to-do, and their first child, Marie (later generally called Mary), was born into a prosperous home. The 1911 census offers us some hints of that prosperity. On census night, which fell on 2 April, Mary and her brother, John, were visiting their uncle, Rev. Waters, and his wife, Jane, at Springfield House, a grand house in Gardiner’s Hill, Cork. John had been born a year after his sister, on 18 May. The children’s nurse, 41-year-old Mary Morgan, was with them.

Elsewhere in the city, Elisabeth Elmes was visiting her sisters, Marion and Juliet, at 17 Belgrave Square, Monkstown, while Edward Elmes was the only family member at home. The household had a second live-in maid, a nineteen-year-old Catholic, Julia Spence. That night she had a visitor, Mary Spence (aged fifteen), perhaps a sister. The fact that the family had two servants says something about their status: they were comfortable members of the professional middle class.18 The children’s nurse and servant lived at the top of the house in relatively spacious communicating rooms with windows overlooking the garden. The house itself was plumbed throughout and the bedrooms were fitted with porcelain wash-hand basins. It had a bath and an indoor toilet.19

There were more luxurious houses in the city at the time, Spring-field House among them, but there was extreme poverty too. A sociological survey by Fr A. M. MacSweeney, conducted a few years later in 1915, foun...