- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When the Celts first arrived in Ireland around 200 B.C., the island had already been inhabited for over 7000 years. Drawing on a wealth of archaeological evidence and the author's own mastery of the subject, Ancient Ireland returns to those pre-Celtic roots in a bid to discover the secrets of the island's first inhabitants: Who were they? And how did they live?

Few accounts of the period are as exhaustively researched; fewer still are as alive with historical insight and compelling detail. At once accessible and comprehensive, Ancient Ireland is an indispensable guide to early Irish civilisation, its culture and mythology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancient Ireland by Laurence Flanagan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

THE ARCHAEOLOGY

1

INTRODUCTION

The discipline that helps us to recognise the artefacts, monuments and events in an Ireland that was not merely pre-Christian but was fairly certainly pre-Celtic as well is archaeology.

Many years ago a young, possibly slightly arrogant—certainly self-confident—archaeologist defined archaeology as ‘the study of social and economic history through the actual commerciable products of society—or in other words the story of Man’s attempts to keep the wolf from the door by means of better doors and better wolf-traps.’ Thirty years later I doubt if I would change a word of that definition, except by pointing out that ‘commerciable products’ includes not only the obvious, such as food, tools, and housing, but also things like tombs and temples, which, even if they have no resale value, have certainly incurred costs in the form of time, labour, and energy.

It is necessary always to remember that although the flint tools, pots, tombs, house plans and decoration so frequently illustrated in archaeological text-books are important, they are important primarily as documents of social history—as clues to how their makers and users eked out a precarious living or enjoyed a lavish life-style. In a photograph of a funerary pot containing the cremated bones of what once was a human being, it is the cremated bones that are vitally important, not the pot: it is primarily important as a sort of fingerprint of the deceased, providing clues about who or what he or she was, how they might have lived, and, finally, how they might have ended up inside it.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Despite the importance of the human being, whether cremated and inside a pot or not—since, as far as we are concerned, prehistoric humans are totally mute and have left no record of their feelings or of their attitudes to life or death or to their fellow-humans—we have to resort to physical evidence that has survived. Essentially this leaves us with the objects they made—the tools, the ornament, the houses, the tombs, reflecting different aspects of their life. In addition, of course, we have the testimony of ‘natural history’—the geology, the zoology, the botany, the biology, the pathology, even the physics—that cast light on their environment and their condition.

Genetics

Unlike the inferences drawn from ethno-archaeological parallels, the laws of genetics are normative and inflexible. They determine whether a population is large enough to survive in a healthy condition or whether it is too small to avoid extinction—and they apply both to human beings and to animals, whether domesticated or wild. The influence exerted by genetics on an isolated island colonised by humans for the first time is considerable, even if, in the past, it has not been considered sufficiently or considered deeply enough. Estimates of population sizes have to be considered with regard to the viability of genetic pools—both for humans and for animals, especially the animals that were introduced by humans to form the basis of their nutrition. The endangered species is not a modern invention, though the concept may be.

Genetics, however, is not all bad news for archaeologists. One of the slightly depressing features of prehistory is that we know the names of none of the people whose bones we may be examining, or merely handling, or whose pot—made by them, or merely used by them—we may be examining for any shreds of information about its maker or user. We can never obtain photographs of them, or recordings of their voices. If, however, DNA ‘fingerprinting’ was applied in the cause of archaeology we could achieve a much closer relationship with them: we could know, for instance, whether we were related to them—or that it is simply impossible for us to be. We could establish whether two people sharing a grave were related, or merely ‘good friends’. In a manner of speaking, it would make them into more real human beings.

Unpredictability

One of the quirks of archaeology is its inherent unpredictability. An archaeologist could today make a reasonably confident statement, ‘No—copper or bronze nails were definitely not used in the construction of buildings in the Bronze Age in Ireland,’ and be proved wrong tomorrow. For many years the lack of evidence of beakers in the southwest of Ireland, where the plenteous supplies of copper are found, has been a dilemma for those who thought that the makers of beaker pottery—the Beaker People—were, notwithstanding this, the most likely people to have introduced metallurgy to Ireland. The recent and unpredicted—though not, in some ways, unpredictable—discovery of the site at Ross Island, County Kerry, with its beaker pottery, its association with copper smelting and its favourable radiocarbon dates has changed all that. Negative evidence is not a very faithful colleague.

In a manner of speaking, the fact that humankind itself is unpredictable is the quintessential stumbling-block for archaeologists. We have to assume that the people whose dwelling-places, artefacts, lives even, we are dealing with were rational, integrated, sane and sensible human beings. Then we look around at our own contemporaries and wonder how this belief can possibly be sustained.

Non-technical and non-practical traits and activities

It is probably inevitable that right from the beginning of the human occupation of Ireland many activities were rife of which we have now no direct—that is, archaeological—evidence. It would seem, from a perspective of modern, and not so modern, society, that sport or games of some sort or other would have been prevalent, even if at Mount Sandel only five-a-side could have competed in the football tournament, kicking the inflated bladder of a pig. Running races would surely have been a popular pastime, right from earliest times—if only because it would have provided fitness and fleetness for the hunt. Perhaps with the introduction of the horse by Beaker People, horse-racing could have become established in Ireland. Religion, of course, in some form or another, was clearly established in the Later Stone Age or Neolithic Period. Court tombs clearly indicate a desire to erect monuments to dead ancestors; perhaps we have not yet discovered a Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) precursor. Passage tombs seem not merely to be an expression of some form of religious belief but, much more than court tombs, of a sort of social supremacy. These innocent-seeming activities might of course have witnessed the beginnings of their ultimate opponents: did the matches between Mount Sandel United and Lough Boora Rovers attract football hooligans? Did the rival religious groups burn each other’s temples? Fortunately, perhaps, archaeology in Ireland does not (or has so far failed to) reveal this kind of truth. The true believer, however, is aware that one of these days it might.

ARTEFACTS INTO ARCHAEOLOGY

The landscape of prehistory is littered with artefacts, as, indeed, is the landscape of Ireland. There are many kinds of portable artefact, made of such varied materials as flint, stone, wood, leather, textiles, bronze, and gold. There are many kinds of non-portable artefact: monuments of various kinds, reflecting different needs on the part of the prehistoric inhabitants, showing different sizes, styles and degrees of complexity and made of materials such as wood or stone—though it is those made of stone that are most likely to have survived. At this stage, however, they are simply dissociated artefacts and reveal little about their makers and users, except, perhaps, that they had a need for different types of artefact for different purposes and that their makers had certain skills in the making of tools or implements of various materials. How do we persuade them to tell their stories?

Flint

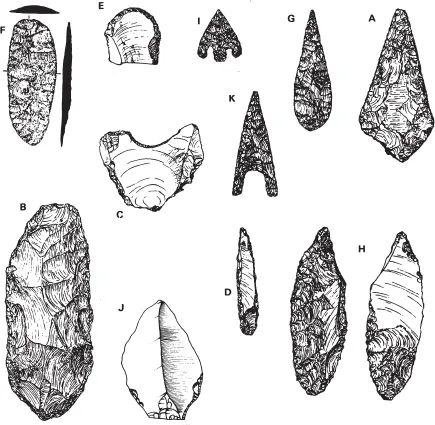

Artefacts of flint not only constitute the earliest prehistoric artefacts but also are the most common. Flint itself is relatively easy to identify (my own eldest daughter could reliably recognise flint at the age of four). On these grounds, therefore, it seems appropriate to look at them more closely and to see what information they can reveal about our prehistoric predecessors. Even for such a seemingly intractable material they exhibit a wide variety of form and, even superficially, suggest a wide variety of types and functions. A selection of flint artefacts is shown in fig. 1.1.

Flint hollow scrapers

From the array of flint artefacts, we have selected one to follow up (fig. 1.1C). It is a fairly broad flake of flint, thin in section, with a pronounced concave feature at one end; because of this pronounced feature, implements of this type are known as hollow scrapers. The shape of the flake varies considerably, and in section it is usually trapezoidal. The ‘hollow’ varies in outline from a broad shallow arc (of a circle as much as 90 or 100 mm in diameter) to an almost semicircular indentation less than 20 mm in diameter, with almost every conceivable intermediate combination of diameter and depth. The finish of this hollow working edge varies from strongly marked serrations to as smooth an edge as the technique of removing small overlapping flakes will permit. On the main hollow (some specimens display more than one) the working of the edge may be executed from either the upper face or the lower (technically known as the bulbar face, from the fact that it is the face that retains the ‘bulb of percussion’—a visible relic of the detachment of the flake from the core).

1.1A selection of flint artefacts of various forms and functions: (A) part-polished javelin-head; (B) core tranchet axe; (C) hollow scraper; (D) double-backed blade; (E) convex scraper; (F) plano-convex knife; (G) leaf-shaped arrow-head; (H) perforator; (I) barbed-and-tanged arrow-head; (J) butt-trimmed ‘Bann’ flake; (K) hollow-based arrow-head (various sources, various scales)

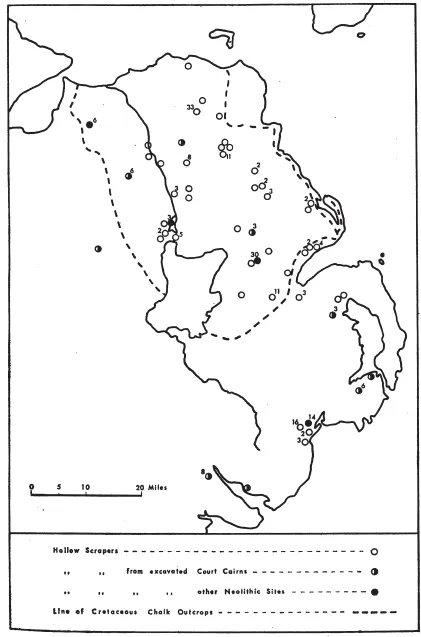

The next stage is to collect together (not necessarily physically) all the known examples of hollow scrapers so that we can see in what parts of the country they occur. Because the flint-bearing outcrop of cretaceous chalk or limestone is restricted to the north-eastern part of the country, it is there that we may expect to find the greatest concentration of flint hollow scrapers (fig. 1.2). And here indeed we find 395 examples, while in the rest of the country we find considerably fewer. (It must be noted that these maps were compiled in 1965 and that the totals both for the north-eastern area and the rest of the country have increased considerably since then, mainly as the result of important excavations in both areas; the overall picture, however, is probably not significantly different.)

The next stage is to establish what other types of object hollow scrapers are found with and in what types of monument, if any. It can fairly quickly and positively be determined that they are frequently found in the burial monuments known as court tombs; in 1965 they had been found in twelve of the twenty-two court tombs that had by then been excavated. They were found with virtually every type and style of Neolithic pottery—except those types specifically confined to the south-west of the country—and with other types of Neolithic flint and stonework, including leaf-shaped and lozenge-shaped flint arrow-heads and ground or polished stone axes. Even more importantly, they were reunited with the people who had made and used them and whose remains were also found in the tombs. Since 1965, of course, hollow scrapers continued to appear in court tombs. They also occur on domestic sites.

1.2The distribution of hollow scrapers in the flint-rich north-east of Ireland (after Flanagan, 1965)

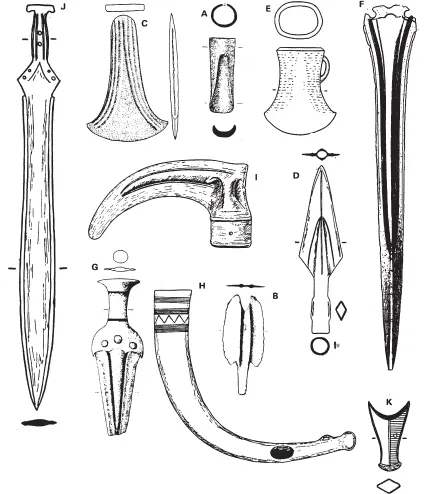

1.3A selection of bronze artefacts of various forms and functions: (A) socketed gouge; (B) razor; (C) flat axe; (D) socketed spear-head; (E) socketed axe; (F) rapier; (G) dagger; (H) horn; (I) socketed sickle; (J) leaf-shaped sword; (K) sword chape (various sources, various scales)

One interesting feature of hollow scrapers is that while they are found virtually throughout Ireland it is only in Ireland that they are found, except for one or two examples from the Isle of Man and a few from the west of Scotland—two areas to which they were probably introduced with court tombs.

Copper and bronze

While by no means the same ultimate quantity of copper and bronze artefacts exists as of flint ones, there is certainly a greater variation in their forms and functions (fig. 1.3). Obviously the same processes can be applied to copper or bronze artefacts as were applied to flint hollow scrapers. The approved style and description of any particular type can be established by a close and careful study of the potential constituent members of the proposed type; the distribution and the ‘catalogue’ of associated types of other artefact can be...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Contents

- Part 1: The Archaeology

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Mesolithic Period, 8000–4000 BC

- Chapter 3: The Neolithic Period, 4000–2000 BC

- Chapter 4: The Court Tombs

- Chapter 5: The Passage Tombs

- Chapter 6: Beakers and the Bronze Age

- Chapter 7: The Earlier Bronze Age, 2000–1200 BC

- Chapter 8: The Later Bronze Age, 1200-700 BC

- Part 2: The Social Prehistory

- Chapter 9: Society

- Chapter 10: Industry

- Chapter 11: Manufacturing

- Chapter 12: The Food Industry

- Chapter 13: Nutrition and Health

- Chapter 14: Domestic and Personal Life

- Chapter 15: Religion and the Arts

- Chapter 16: Technology and Science

- Chapter 17: The Environment

- Glossary

- Sources

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About Gill & Macmillan