![]()

1

PRELUDE TO A LEGEND

In a quiet countrified part of south London, sheltering in the cloister of a famous school of ancient lineage, resting on a bed of grey South Atlantic boulders, is a small boat, painted white and ketch-rigged, with all sails set.

Undoubtedly the most famous small boat in existence, she has been displayed at the school, off and on, since 1924. Yet the schoolboys jostle past her day in day out, with hardly a glance. She is a part of their everyday existence.

Yet for visitors who make the pilgrimage from distant places, such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and Scandinavia, to see her, as well as from many parts of Britain, she is more than a boat: she is an icon, a marvel, a stimulus to the imagination.

In 1916, this small boat played a vital part in an incredible journey which saved the lives of 28 ship-wrecked men. She epitomises, perhaps better than any other existing artefact, the extraordinary qualities of the man who led the expedition and masterminded the rescue.

The man was Sir Ernest Shackleton, the boat is the James Caird, and the school, Shackleton’s alma mater, Dulwich College. The date of the voyage was April to May 1916.

The James Caird is the 23-foot-long ship’s boat which the explorer, Sir Ernest Shackleton, with five companions, sailed from Elephant Island, south of Cape Horn, to South Georgia, in 1916. This 800-mile voyage in an open boat, through the Southern Ocean in early winter, renowned among mariners for its fierce gales and enormous seas, ranks as one of the greatest feats of seamanship in the long history of seafaring.

The James Caird at Dulwich College

Shackleton’s boat is now preserved at Dulwich College, his old school in south London. But for the enthusiasm of some Norwegian whalers, who insisted on rescuing what remained of her from the ice-strewn beach where she had ended her voyage and shipping her on to England in 1919, she would not be here to remind us of that epic feat. Indeed, apart from the historic film and photographs taken by the expedition photographer Frank Hurley, and a Bible, a log, a sextant and a Primus stove, still preserved, the James Caird is almost all that remains of Shackleton’s well-found expedition in the Endurance, which set out in 1914 to undertake the crossing of the Antarctic continent from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea, but met with disaster.

With four Antarctic expeditions to his credit, no man has left a more enduring mark nor stamped his personality more firmly on Antarctica than Shackleton. The map of the southern continent is littered with features that bear his name, from the Shackleton Range of mountains to a glacier, an ice fall, an inlet, a coast and many others. When Sir Vivian Fuchs led the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition in 1955, he gave the name of ‘Shackleton Base’ to his starting point in honour of the man who had set out to cross the continent nearly half a century before.

Born near Dublin on 15 February 1874, but descended from a Yorkshire family, Ernest Henry Shackleton grew up in south London. Since he was determined to go to sea, his father, almost in desperation, arranged for him to leave his school, Dulwich College, early and at the age of sixteen, enter the hard world of square-rigged sailing ships. By good fortune, Shackleton senior’s cousin ran the Mission for Seamen in Liverpool, who saw to it that his nephew would be in the hands of a good captain. Bound apprentice to qualify as an officer, young Ernest rounded Cape Horn five times within two years and twice his ship was dismasted. He gained the reputation of being out of the usual run, a hard worker, a good mixer, a spellbinding storyteller and a lover of poetry, particularly the works of Browning, from which he could quote at length.

A square-rigger in a gale

Shackleton as a boy

Shackleton in cadet rig

By 1898, at the early age of 24, he had gained his Master’s ‘ticket’, which qualified him to command a British ship anywhere in the world. But the prospect of a relatively mundane life in ocean liners did not appeal to him. When the urge for adventure, fame and fortune coincided with opportunity, he grasped it eagerly. For the rest of his life, over a period of some twenty years, the frozen wastes of the Antarctic were to dominate his career and absorb all his abundant energy.

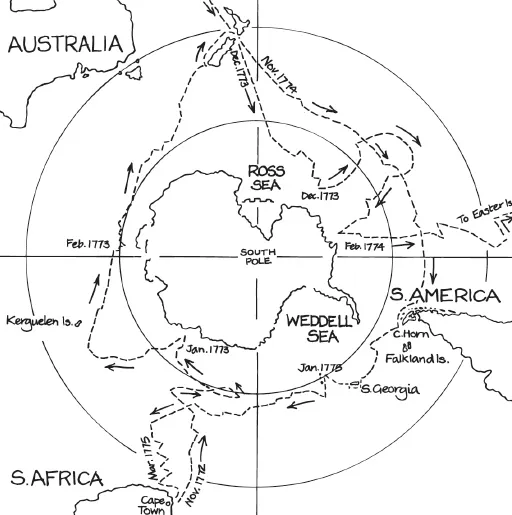

Thanks to a century of exploration by sea, land and air, the geography of Antarctica is now well documented. Two centuries ago no one even knew such a continent existed. Early explorers had sought new land in the south in the hope that, beyond the Tropic of Capricorn, a new El Dorado, to rival South America, waited in the South Pacific with vast riches in store for the nation fortunate enough to discover it. That a large land mass must exist in the Southern Hemisphere was confirmed by Captain Cook, the great eighteenth-century navigator. On his third voyage in 1774, Cook reached the latitude of 71° 10′ South, well beyond the Antarctic Circle. In conditions of extreme cold, high seas and gale-force winds, he was only halted by an impenetrable barrier of pack ice. Cook reported that land almost certainly existed beyond the ice barrier, because the ice of the enormous bergs they encountered consisted of frozen fresh water which could only come from land-based glaciers. Nevertheless, any land could only be a wilderness of ice and snow, uninhabited and worthless.

Track of Captain James Cook's expedition 1772–75

Captain James Clark Ross RN

Ross’s ships Erebus and Terror

Early in the nineteenth century a handful of explorers, including three Britons, Biscoe, Bransfield and Weddell, Bellingshausen, a Russian, and many others, ventured into the Southern Ocean. Accounts of their voyages brought a flood of seal hunters, and later, whalers, in their wake. None was able to penetrate the pack-ice barrier until Sir James Clark Ross – then Captain Ross RN – led an expedition to locate the South Magnetic Pole. With twenty years’ experience in the Arctic, he was given carte blanche to equip his expedition. He sailed south with two vessels, Erebus and Terror, which had been specially strengthened and equipped for work in the ice.

In 1841 Ross approached the continent from the Pacific Ocean, forced a passage through the pack ice and broke through into clear water beyond. He gave his name to the Ross Sea but did not land on the continent, for he found a forbidding coastline of huge ice cliffs now known as the Ross Ice Shelf or Barrier. He had a view of mountains, 10,000 feet high, in the distance beyond. He also named Ross Island, which was distinguished by two huge volcanoes, towering straight out of the sea. He named them after his ships; Erebus rose to a height of over 12,000 feet and was still active, while Terror was only 1,500 feet lower. He penetrated beyond Ross Island and entered McMurdo Sound,1 unwittingly discovering the nearest land approach to the South Pole.

Interest in the southern continent then lapsed until the end of the century, when the Sixth International Geographical Conference, held in London in 1895, issued a challenge to the nations to unravel the secrets of this vast unknown wilderness. Polar exploration until then had been concentrated on the Arctic, and the search for the North West Passage. In an atlas of that date, the first illustration showed the ‘North Polar Chart’, although a large area round the North Pole is marked ‘unknown region’. There is no corresponding map of Antarctica. No one had ever set foot on it although its area was equal in size to the whole of North America. Protected by a barrier of ice which only Ross had pierced, surrounded in its turn by the Southern Ocean – the most storm-swept waters in the world – it was about to become the latest challenge to the world’s expl...