![]()

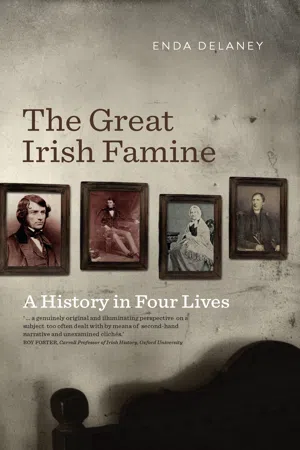

Cover

Title page

Dedication

Preface

Prologue: The land of the dead

Part I. Before the Famine

Chapter 1: Encounters

Chapter 2: Land and people

Chapter 3: Politics and power

Part II. That coming storm

Chapter 4: Spectre of famine

Chapter 5: Peel’s brimstone

Part III. Into the abyss

Chapter 6: A starving nation

Chapter 7: The fearful reality

Chapter 8: Property and poverty

Part IV. Legacies

Chapter 9: Victoria’s subjects

Chapter 10: Exiles

Epilogue: The death of Martin Collins

Notes

Bibliographical Note

References

Images

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill & Macmillan

![]()

The Great Famine of 1845–1852 was the defining event in the history of modern Ireland. Proportionately one of the most lethal famines in global history, the consequences were shocking: at least one million people died, and double that number fled the country within a decade.

The work of a whole generation of scholars since the 1980s has laid bare the brutal realities of the late 1840s in a raft of detailed and pioneering studies. My heavy debt to this body of scholarship will be evident from the notes. This book does not present detailed findings based on consulting large amounts of new evidence or hitherto unknown archival documents, as the relevant material has been extensively worked through by other people. On certain essential points it does incorporate original research on contemporary sources; nevertheless the objective is to draw on the existing scholarship, much of it not accessible to a broader audience, and present a distinctive interpretation. This is therefore a narrative history, with an interpretative dimension. It gives equal weight to the social, economic and political aspects of the crisis. My purpose in writing the book is to further our understanding and deepen our knowledge of those most horrific years in the complex and fascinating history of modern Ireland.

![]()

PROLOGUE

The land of the dead

An engraving of Bridget O’Donnell and her children that appeared in the Illustrated London News in December 1849 put names and faces on the victims of Ireland’s Great Famine. It remains one of the most widely recognised images of the crisis: a woman in rags, with sunken face and limbs emaciated, beside two young children. According to an accompanying news story, her husband had held a little less than five acres in the townland of Garraunnatooha in the parish of Kilmacduane, near Kilrush, Co. Clare, but the family had been evicted for falling behind in the payment of rent. They had purchased oats for seed from Marcus Keane, who owned the land, and they had sown the crop and harvested it. As soon as the corn was stacked, a neighbour named Blake had taken the corn and stored it, on the instructions of one Dan Sheedy, presumably a henchman acting for Keane. Sheedy then arrived with a group of men to eject the family and level the cabin. Bridget, pregnant and suffering from fever, remained inside, until neighbours rescued her. A week later she gave birth to a stillborn child and received the last rites from her priest, the Rev. Michael Meehan. Another child, aged thirteen, died three weeks later. Sheedy and Blake sold the corn at the market in nearby Kilrush.1 What happened to Bridget O’Donnell thereafter has never been established.

Marcus Keane was a notorious agent who represented absentee landlords in Co. Clare, such as Francis Conyngham, second Marquess Conyngham, but was himself the owner of a small estate. In addition to the O’Donnells he had evicted twelve other families in Garraunnatooha, leaving some sixty people homeless.2 He was described in 1846 by a state functionary as a ‘gentleman of high character’; the Limerick Reporter later said of him that he was ‘unhappy when not exterminating’,3 and one historian has described him as the ‘exterminator general’.4 Keane earned this notoriety through the large-scale evictions he oversaw throughout Co. Clare, especially in the Kilrush Poor Law Union from 1847 onwards.5 The Poor Law inspector for the union, Captain Arthur Kennedy, drew the attention of senior officials in London to his systematic removal of smallholders during 1848 and 1849.6 Ultimately a parliamentary committee chaired by the radical mp George Poulett Scrope examined the whole issue of the shocking events that had taken place in the Kilrush Union during the previous three years.

The reporter from the Illustrated London News who recorded Bridget O’Donnell’s story had been despatched to west Clare to investigate the mass evictions in late 1849. On entering a village he felt he was transplanted to ‘the land of the dead’.

It is a specimen of the dilapidation I behold all around. There is nothing but devastation, while the soil is of the finest description, capable of yielding as much as any land in the empire. Here, at Tullig, and other places, the ruthless destroyer, as if he delighted in seeing the monuments of his skill, has left the walls of the houses standing, while he has unroofed them and taken away all shelter from the people. They look like the tombs of a departed race, rather than the recent abodes of a yet living people, and I felt actually relieved at seeing one or two half-clad spectres gliding about, as an evidence that I was not in the land of the dead.7

The orders to clear estates of smallholders came from landlords or from agents acting for them. After the necessary legal processes were completed they were executed by gangs of men known as ‘wreckers’. From similar poor backgrounds to those of the evicted tenants, these were hardened young men. ‘Rough-looking peasants’, they were known for drinking heavily before they got down to wrecking.8

When the legal processes of eviction and levelling had been done, the wreckers set about removing the evicted tenants from the public roads near their old homes, along which many often set up makeshift shelters. After one eviction, on 22 October 1850, recounted by the English philanthropist Lord Sidney Godolphin Osborne in a letter to the Times (London), a family threw up a scalp (a makeshift shelter made of sods) on the roadside. When the husband was away his wife visited a nearby neighbour about a hundred yards distant. A girl called out that the scalp was on fire, and the woman ran back to save her child, but it was too late. The distraught mother arrived in time to witness her child being ‘taken out of the scalp on a shovel, all burnt to death, by a man named Michael Griffin’. She knew that the tragedy was no accident: ‘I am sure that the scalp was set on fire by some person or persons, for it could not otherwise take fire’.9

Brutal evictions, occasionally with lethal consequences, were but one symptom of the complete disintegration of Irish society by the late 1840s; the exodus of a quarter of a million people in one year, 1851, was another. The complete failure of the potato crop in 1846 and 1848, with partial failures in other years, was the result of a destructive blight that destroyed the food that at least a third of the people of Ireland relied on for survival. First and foremost, it was this unprecedented environmental disaster that created widespread hunger.

This book describes how Ireland descended into chaos in the middle of the nineteenth century. Yet the country was politically integrated in the United Kingdom, the most advanced industrial economy in the world. It lays special emphasis on the conditions on the eve of the famine, before the blight struck in September 1845, as this served to expose the existing weaknesses in Ireland’s political, economic and social structure. Particular attention is paid to the role of the British state in responding to hunger in Ireland. Rather than just creating a need to feed the poor, the outbreak of famine was seen by influential British politicians and officials as presenting a unique opportunity to implement far-reaching changes in Irish society. For some of an evangelical bent this was a divinely ordained moment for bringing about root-and-branch reform in the organisation of the rural economy; for others, reason and logic, together with Divine Providence, demanded that an archaic peasant culture be eradicated and replaced with a capitalist form of agriculture. The fatal decisions that led to hundreds of thousands of people being placed on the edge of starvation were taken by these ‘enlightened’ men in the context of an ideological policy that lauded the transformative power of the state. Legislative measures such as the introduction of the Poor Relief (Ireland) Act (1838) were the work of rational improvers who sought to impose an orderly structure on what was considered an uncivilised society.

What was self-consciously ‘progressive’ social engineering had a cruel outcome. People would undergo great suffering, many would die or be forced into the workhouse or emigration, but at the end of this painful process a stronger and more rational society would gradually emerge. The application of these principles had horrific, almost unimaginable consequences for the Irish poor.

The British government cannot be singled out for the inadequate, and at times inhumane, response to the famine. Many of those who made up the upper and middle classes, both Catholics and Protestants, landlords, farmers and merchants, stood by as millions of poor people simply vanished from the landscape. The Great Irish Famine had winners as well as victims, as self-interest overrode basic humanitarian concern for the vulnerable and powerless.

This book chronicles the tragic sequence of events that unfolded during the late 1840s and early 1850s by placing a strong emphasis on the experiences and contrasting viewpoints of four contemporaries.

Elizabeth Smith, née Grant (1797–1885), came to Ireland through sheer chance when her husband inherited an estate in west Co. Wicklow in 1830 and remained in the country for the rest of her long life. She was a perceptive observer of Irish life in her volumes of diaries, occasionally acerbic and adopting the high moral tone typical of her social class. She could also be very sympathetic to the plight of the poor in her locality of Baltiboys, near Blessington. In her lifetime she was anonymous: only after her niece Lady Strachey published her memoirs in 1898 did she come to public notice.

John MacHale (1791–1881), Catholic Archbishop of Tuam, was one of the most popular figures in nineteenth-century Ireland. Hated by some British politicians and his many Irish enemies, clerical and lay, he was loved by his devoted flock for his popular radicalism and concern for the poor. He was the classic patriot-bishop, known as the Patriarch of the West or, as Daniel O’Connell dubbed him, the ‘Lion of the West’ or the ‘Lion of the Fold of Judah’.

Sir Charles E. Trevelyan (1807–86) was assistant secretary to the Treasury, the most senior official who oversaw relief efforts in Ireland. A reforming and conscientious public servant with strong religious convictions, he often privileged principles over common sense in his decisions. As the person associated to this day with British parsimony during Ireland’s Great Famine, he remains a controversial figure.

The final figure is John Mitchel (1815–75), the famous nineteenth-century nationalist writer whose passion and radical views on the shortcomings of the British government of Ireland helped create a deep sense of grievance among the Irish diaspora, especially in the United States. His most famous judgement may be: ‘The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight. But the English created the Famine.’

Each of these characters brings a unique viewpoint, influenced by who they were, what they witnessed, and what they stood for. Human failings are evident in the actions and personalities of each of them, whether this be Trevelyan’s unflinching commitment to administrative rectitude over and above all other considerations, Smith’s instinctive abhorrence of Catholicism, MacHale’s disputatious nature, or the ferocity of Mitchel’s hatred of everything English. Retelling the well-known events of the Great Irish Famine through the lives and experiences of these four very different individuals allows for an intimate view on these tragic years.

Our story opens in Co. Mayo in the late 1790s.

![]()

| PART I

Before the Famine

![]()

DEATH OF A PRIEST

Piercing wails reverberated through the steep ravine known as the Windy Gap and were heard miles away. A procession wound its way gingerly along the mountain path. At its head, a small group carried a corpse. The news spread rapidly among the inhabitants of Addergoole. Hundreds marked the route as the much-loved priest was brought home, back to his chapel and final resting place. At the foot of Nephin, a place of immense natural beauty where the tall mountain peak runs down to meet Lough Conn, he was buried.

The origin of this tragedy was in the turmoil of the 1798 Rebellion. French forces led by General Jean Humbert arrived in August 1798 at Killala Bay, on the coast of Co. Mayo. They made quick progress inland, with the intention of joining Irish rebels who were engaged in the uprising against the Crown in the north and east. The French camped in Lahardaun, the village within the parish of Addergoole. The parish priest, Andrew Conroy, had been educated in France and spoke French. A number of the officers called at his home, and local legend has it that he gave directions to the invading force on how to reach Castlebar through the Windy Gap, thus avoiding the normal route along the Foxford road. No-one knows how much assistance he gave, and contemporary accounts present widely divergent versions. Sir Richard Musgrave, in his partisan history of the 1798 Rebellion, charged Conroy with entertaining the French, making food available to them and stopping a messenger from passing word to the British forces that the French were advancing towards Castlebar.

The small French force, together with Irish volunteers, achieved a victory at Castlebar on 27 August 1798 in the battle that became known as the ‘Races of Castlebar’, because of the speed of the retreat of the exhausted Crown forces. A vital factor was that the French and Irish approached the town through the Windy Gap, which the British forces did not believe was passable by an army with artillery and so had left undefended. It was just about traversable for a lightly equipped force, and Conroy certainly knew this. After first pretending to take the Foxford road, the French doubled back and marched through the night over the mountain track.

In the wake of the failed uprising Denis Browne, the chief magistrate of the county and a prominent member of the local Protestant ascendancy, rounded up all the county’s inhabitants believed to have assisted the French. They were to be treated as traitors and shown no mercy, and his arbitrary justice dispensed to the local people who joined the French earned him the nickname of ‘Denis the Rope’. Browne’s house in Claremorris, along with those of other prominent Mayo government supporters, was sacked by Irish rebels during the uprising. Father Conroy’s actions in...