![]()

1

Making the Generous Cooking Pot, ca. 1890–1920

AT THE beginning of the twentieth century, food production and preparation ordered much of daily life in the French Soudan. Women’s labors in this realm assured the quotidian meal and the social practice of food sharing. A folktale from this period featuring a magical cooking pot reveals the considerable value of this labor and the importance of generosity as a cultural ideology in the region. The story opens as a hyena, a character that often served to comically highlight human missteps, sets out to find fortune.1 While traveling, the hyena searches for something to eat and comes across a monkey and a tortoise. The hyena hopes in vain that the two animals will help gather fruits from a baobab tree and edible water lilies, but the monkey stays in the branches of a tree and the tortoise disappears into the water of a marsh. Their refusal to help the hyena find food signals a social ill for the listeners of the tale. On the same journey, the hyena finds a lump of butter, the mythical food first offered to humankind in Bamana traditions and a symbolic substance associated with women and fertility.2 Unfortunately, the hyena loses the butter in an attempt to cook it directly over a fire for want of a pot. Not long into the hyena’s search for fortune, how to find food and prepare it has become a central element of the tale. Following these failed attempts to procure sustenance, the hyena discovers a small cooking pot in the marsh where the tortoise disappeared.3 The hyena asks the pot for its name and receives the reply “the Generous Cooking Pot.” When asked to offer generosity, the pot miraculously produces cooked rice, couscous, and meat.

Then, as was custom in the region, the hyena—like a human traveler—seeks a local host. In this story it is an elderly hostess. Shortly after finding the magical pot, the hyena demonstrates its powers to the old woman, who is similarly astounded. Rather than employ the pot to cook for her guest, however, she decides to present the powerful object to the king. The hyena, endeavoring to retrieve the pot from the king, returns to the marsh and finds a sword that attacks anyone asking for its name. When the hyena offers the sword to the king, its attack distracts him long enough for the hyena to recover the pot and flee. It is a tale that reveals much about daily life in the region. Indeed, for the hyena and the tale’s audience, fortune was found in the generosity of the cooking pot.4

Strangely, it is a woman who gives up the pot once it is presented to her, and perhaps it is this irony the audience is meant to take away from the story. Managing the pot and generously sharing food was the realm of women, not political leaders, whose raids and wars in the late nineteenth century provoked food shortages. Yet the relationship between women, abundance, and the state is complicated in the long history of the region. Interestingly, in the story the woman is elderly and no longer able to produce children, suggesting a connection between female fertility and food production.5 Nevertheless, the old woman’s character does testify to the great power of a technological object strongly associated with women and the provision of food. In the story, the pot repeatedly produces a rich meal from what appears to be nothing. The magical cooking pot is the very essence of hospitality. It also symbolizes the essential role of food production in rural life and how state politics and violence complicate food production. But even more, the pot represents the desire to be fully satiated. This cultural ideal was manifest during yearly agricultural festivals, when women prepared seemingly endless amounts of food and beer. Yet it was not an easy feat for women to emulate the pot’s generosity in times of scarcity or political upheaval.

The French Soudan was predominantly rural, but the conditions for agricultural production were changing during the first decades of the century. Indeed, women’s gathering, cultivation, and culinary skills were vital as farming households faced environmental stresses, demographic shifts, political insecurity, and increasing colonial intervention. The years of conquest in the decades before 1900 had upended daily life and provoked widespread migration, leaving many fields untended. Not long after the French began to establish colonial rule, the devastating 1913–14 famine left thousands in dire conditions. As the first decades of the twentieth century unfolded, the French would pressure those same rural populations to produce for new colonial markets. In the midst of rapid and dramatic change, women adapted their cultivation and preparation techniques to ensure their pots would continue to produce food.

GENDER AND EMBODIED LABOR

In the second decade of the twentieth century, another story circulated in the French Soudan featuring a young woman endowed with the fantastical skill to cook quickly. In the story she prepares an ordinary meal, one the audience understood required hours of labor. Yet her meal is ready seemingly in the blink of an eye. It is a testament to vernacular thinking about women’s expertise. In the same tale, the young woman is compared to her husband and his younger brother, who also accomplish ordinary tasks with astonishing speed. The husband prepares meat from an antelope before the ball from his musket even reaches the animal. His younger brother humorously slips in the mud on the way to the fields. At the same time he saves a basket of seeds from overturning, which he had been carrying on his head. His accomplishment is to quickly change out of new and unsoiled clothes into older ones better suited to the tasks of farming.6 Taken together, the three feats underscore the continued centrality of food production: grain cultivation in the fields, the provision of meat through hunting, and women’s cooking. The story also reflects an idealized division of labor and endows both men and women with extraordinary abilities related to their gendered food labors.

In other stories dating to the early twentieth century, food is similarly produced as if by magic, but the corpus of regional tales also features, less idealistically, greedy characters hoarding food and entire villages suffering from famine. Such tales resembled actual histories of food shortages, hunger, and famine from the period. In many of these stories food signified moral lessons on the importance of hard work and generosity, and specifically the sharing of meals.7 Women cooks, like the fantastically fast woman in the tale, produced the symbolic value of food in regional culture, but throughout the twentieth century their labor was also critical to the material production of rural subsistence in ways unseen in this tale and others.

The story about the three surprisingly fast family members, in particular, suggests the embodied nature of food production in rural Mali. Each of the three characters displays the remarkable ability to quicken ordinary physical movements associated with farming or the production of the evening’s meal. However, the younger brother’s comical fall suggests that he is still learning how to be a farmer. Moreover, the quickly averted loss of seeds gestures toward real risks to the harvest. Embodied knowledge was critical to rural survival but required cultivation. By contrast, the young woman in the story had mastered her embodied cooking tasks. Once the men return from the fields and the chance hunt, she tells the younger brother to bring her some millet from the granary so she can begin cooking. He brings her two baskets of grain, and when he arrives with the third basket full, she announces the meal is ready. She even chastises her brother-in-law for almost dropping unprepared grains onto the finished meal.8 We are not told about the young woman’s actions in detail, but the audience would have been well aware of the time-consuming and fatiguing work that she rapidly completes. In short, like the Generous Cooking Pot, she is a fantastical cook.

Women’s work producing food was physical, and in this story it is valorized alongside the men’s labors. In the conclusion to the story, the narrator asks the audience (in its original telling the story was meant to be interactive) who of the three characters is the fastest worker? The men’s work in the fields and in providing meat was valuable. All the same it is noteworthy that a female cook is potentially as heroic as her husband, the hunter, an iconic figure in the regional cultural imagination.9 And perhaps both are especially impressive when compared to the clumsy younger brother. Yet women in the audience likely chose the cook as the fastest character. Ultimately, women’s expertise in performing quotidian physical labor is lauded in the popular tale.

Women’s cooking in the midst of shortages was especially astounding. For many in the region, the mythical figure Muso Koroni embodies the labor and pain of women who in times of ecological crisis produced something to eat. Muso Koroni is a female deity credited with introducing cultivation techniques to human society. However, it is only through her pain that she transmits these techniques. Muso Koroni and her male companion deity, Pemba, create much of the material world, but she instills chaos, which angers Pemba. In response Muso Koroni takes flight, only to be chased by a third god, Faro, who floods the earth as she runs. Faro’s actions restore order, but Muso Koroni is left to wander and suffer from hunger. To survive, she learns to collect food in the wild and to plant seeds for cultivation.10 The myth shares many elements with historical research on how women’s gathering of seeds led to seed cultivation. When women collected seeds and nuts, they carried them and planted some of them, sometimes deliberately, sometimes accidentally.11 In the French Soudan, women evidently retained and continued to pass down the knowledge of this seasonal, varied, and opportunistic aspect of food production.12 Into the twentieth century, women continued to depend upon and shape a food-gathering capacity in their daily labor. While Muso Koroni’s pain and physical labor was transmitted to human society, productive human activity that creates bodily pain and fatigue is understood as a creative and noble endeavor.

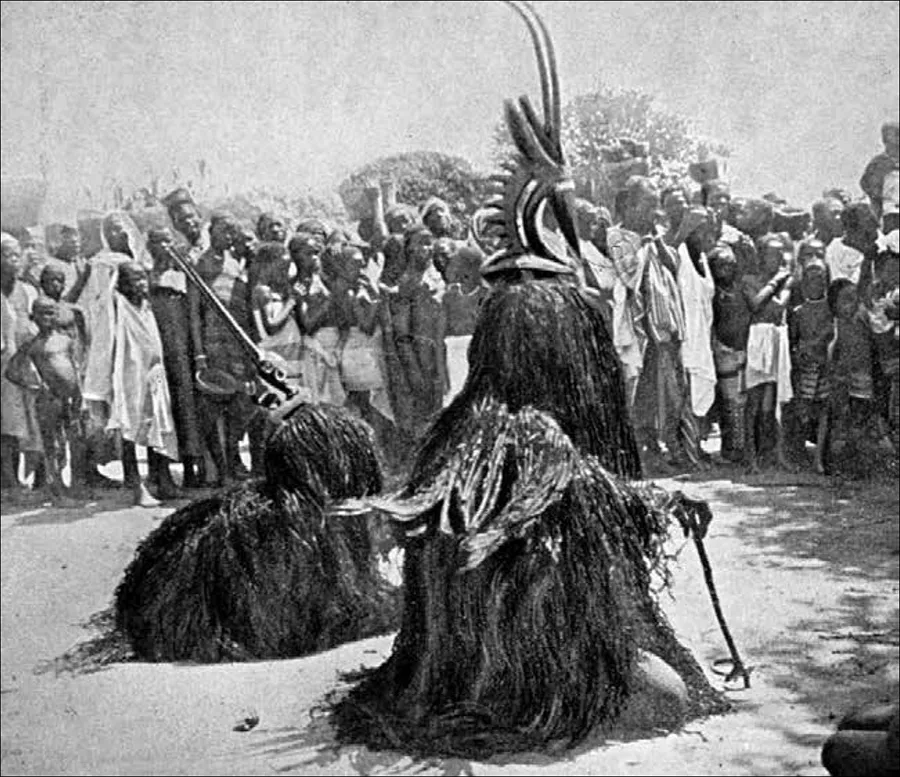

The Muso Koroni myth speaks to regional ideologies about gender as well as labor. In fact, she is credited with innovating the rites that inscribed gender on human bodies (even though elements of both genders were understood to exist in male and female bodies). This original gendering of the body was associated with human procreation but also with the ideal of complementarity in the organization of human society.13 Gendering the body produced specifically gendered labor tasks. For example, women’s food production specifically included the fatiguing labor of collecting wild foods (not unlike the Muso Koroni myth). At the same time, men shared the legacy of producing subsistence through physical hardship. In fact, regional agricultural rites celebrate the tired arms and bodies of male farmers. For example, Ciwara dancers encouraged farmers to work hard during the agricultural season, and their bent-over dance positions purposefully fatigued the dancers’ bodies, who in so doing shared in the overall physical labor of the harvest (see figure 1.1).14 Women also worked in the fields, but their ritually celebrated labor drew together agriculture, fertility, and childbearing. In particular, Ciwara agricultural rites featured a male and female antelope mask in ceremonial performances. The female antelope was distinguished by the representation of a baby on its back, mimicking the actions of women who carry infants in the same manner (worn by the dancer in the background of figure 1.1). The mask connected agricultural fertility to human fecundity. In this regional tradition, childbirth was akin to farming labor—both were productive and procreative but also painful. Childbirth, in particular, was understood to ennoble women.15 It also centered women in the work of human survival and social reproduction.

FIGURE 1.1. Pair of masked Ciwara dancers by Rev. Père. Joseph Dubernet. From Joseph Henry, L’âme d’un peuple africain: Les Bambara leur vie psychique, éthique, sociale, religieuse, vol. 1 (Munster, Aschendorff, 1910), 144 bis.

Returning to the Muso Koroni myth and the figure of the surprisingly fast cook, when drawn together, an important tension emerges: women’s critical labor was widely understood to be physically taxing but was ideally performed as if women were endowed with extraordinary physical powers. These popular representations of women evoke the early twentieth-century cultural discourses shaping regional understandings of women’s social roles and labor. Strikingly, both the story and myth emphasize women’s bodies. In the myth, Muso Koroni’s bodily experience of hunger and fatigue is highlighted. Moreover, the changing material reality of the earth (its flooding and the presence of wild resources) shapes her wanderings. In the tale about the wife who is a fast cook, her ability to prepare a meal so quickly highlights women’s embodied expertise. Both representations signal that women’s experiences are rooted in the material—the material world of floods, hunger, and fatigue—but also in control over the body. Women mediate these material challenges with technologies like pots, but that labor also requires specific corporeal techniques.

To get a sense of this daily embodied and sensorial labor, imagine a woman winnowing grains by using the wind. She would have stood tossing grains up in the air from a calabash. She then would judge when the grains were clean by...