eBook - ePub

Mastodons to Mississippians

Adventures in Nashville's Deep Past

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Winner of the Tennessee History Book Award (Tennessee Historical Society and Tennessee Historical Commission), 2021

Was Nashville once home to a giant race of humans?

No, but in 1845, you could have paid a quarter to see the remains of one who allegedly lived here before The Flood. That summer, Middle Tennessee well diggers had unearthed the skeleton of an American mastodon. Before it went on display, it was modified and augmented with wooden "bones" to make it look more like a human being and passed off as an antediluvian giant. Then, like so many Nashvillians, after a little success here, it went on tour and disappeared from history.

But this fake history of a race of Pre-Nashville Giants isn't the only bad history of what, and who, was here before Nashville. Sources written for schoolchildren and the public lead us to believe that the first Euro-Americans arrived in Nashville to find a pristine landscape inhabited only by the buffalo and boundless nature, entirely untouched by human hands. Instead, the roots of our city extend some 14,000 years before Illinois lieutenant-governor-turned-fur-trader Timothy Demonbreun set foot at Sulphur Dell.

During the period between about AD 1000 and 1425, a thriving Native American culture known to archaeologists as the Middle Cumberland Mississippian lived along the Cumberland River and its tributaries in today's Davidson County. Earthen mounds built to hold the houses or burials of the upper class overlooked both banks of the Cumberland near what is now downtown Nashville. Surrounding densely packed village areas including family homes, cemeteries, and public spaces stretched for several miles through Shelby Bottoms, and the McFerrin Park, Bicentennial Mall, and Germantown neighborhoods. Other villages were scattered across the Nashville landscape, including in the modern neighborhoods of Richland, Sylvan Park, Lipscomb, Duncan Wood, Centennial Park, Belle Meade, White Bridge, and Cherokee Park.

This book is the first public-facing effort by legitimate archaeologists to articulate the history of what happened here before Nashville happened.

Was Nashville once home to a giant race of humans?

No, but in 1845, you could have paid a quarter to see the remains of one who allegedly lived here before The Flood. That summer, Middle Tennessee well diggers had unearthed the skeleton of an American mastodon. Before it went on display, it was modified and augmented with wooden "bones" to make it look more like a human being and passed off as an antediluvian giant. Then, like so many Nashvillians, after a little success here, it went on tour and disappeared from history.

But this fake history of a race of Pre-Nashville Giants isn't the only bad history of what, and who, was here before Nashville. Sources written for schoolchildren and the public lead us to believe that the first Euro-Americans arrived in Nashville to find a pristine landscape inhabited only by the buffalo and boundless nature, entirely untouched by human hands. Instead, the roots of our city extend some 14,000 years before Illinois lieutenant-governor-turned-fur-trader Timothy Demonbreun set foot at Sulphur Dell.

During the period between about AD 1000 and 1425, a thriving Native American culture known to archaeologists as the Middle Cumberland Mississippian lived along the Cumberland River and its tributaries in today's Davidson County. Earthen mounds built to hold the houses or burials of the upper class overlooked both banks of the Cumberland near what is now downtown Nashville. Surrounding densely packed village areas including family homes, cemeteries, and public spaces stretched for several miles through Shelby Bottoms, and the McFerrin Park, Bicentennial Mall, and Germantown neighborhoods. Other villages were scattered across the Nashville landscape, including in the modern neighborhoods of Richland, Sylvan Park, Lipscomb, Duncan Wood, Centennial Park, Belle Meade, White Bridge, and Cherokee Park.

This book is the first public-facing effort by legitimate archaeologists to articulate the history of what happened here before Nashville happened.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mastodons to Mississippians by Aaron Deter-Wolf,Tanya M. Peres in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Making Sense of Nashville’s Deep Past

In 1845 workers digging a well on William Shumate’s farm, located seven miles south of Franklin, uncovered a giant skeleton. Around fifty feet below the surface the well shaft encountered a fissure in the limestone bedrock, at the base of which lay a collection of massive bones belonging to an American mastodon. This was not the first mastodon discovery in America, or even in Tennessee. By that time, remains of Mammut americanum, an extinct species of ice age elephant, had been recovered from various locations throughout the eastern United States for more than a century. Those skeletons were enthusiastically reported on in newspapers and historical texts, and displayed with great fanfare in natural history museums of the era.1 In his 1823 work The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee, Judge John Haywood, also known as the “Father of Tennessee History,” reported discoveries of at least five fossilized elephants in Tennessee.2 By 1845 and the discovery on Shumate’s farm, the total number had climbed to nearly twenty.3

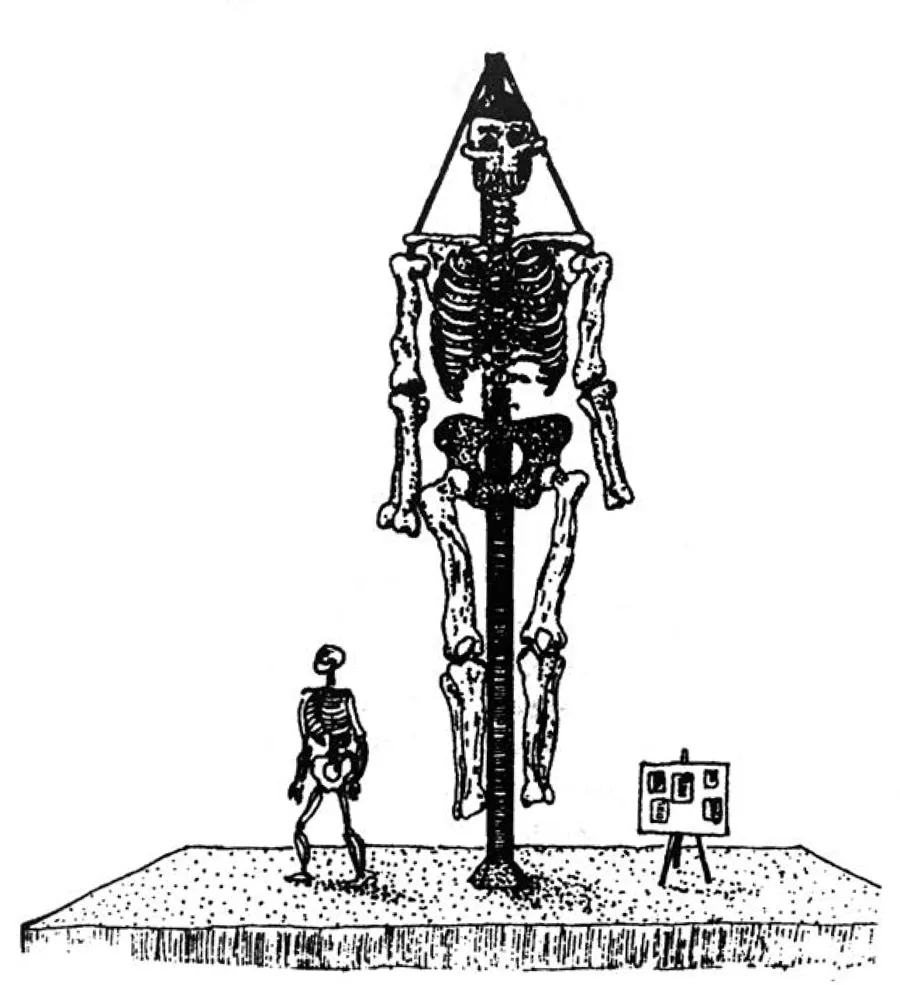

Like many fossil skeletons of the era, the Shumate Mastodon was displayed for the public’s viewing pleasure. There was, however, a twist: mounted upright on two legs and improved by the addition of wooden pieces to replace missing portions of the skull and pelvis, the skeleton was billed not as an ancient elephant, but rather as the remains of an Antediluvian giant human (Figure 1.1).4 The “grand Monster Tennessean” was first displayed at the old courthouse in Franklin, where the price of admission was set at twenty-five cents. The skeleton then moved north to Nashville in December of 1845, where it was installed alongside an average-size human skeleton. Due to popular demand, the price of admission increased to thirty cents, though with a 50 percent discount for servants and children. From Nashville, the exhibit embarked on a tour to New Orleans, where the fraud was quickly recognized by a medical professor. The skeleton disappeared from public view, although not before convincing thousands of visitors that the Nashville area was once home to an ancient race of giant humans.

FIGURE 1.1. Sketch of Shumate’s “grand Monster Tennessean.” When exhibited in Nashville in December 1845, the mastodon remains were mounted upright beside an articulated human skeleton for scale. After James X. Corgan and Emmanuel Breitburg, Tennessee’s Prehistoric Vertebrates, Tennessee Division of Geology Bulletin 84 (Nashville: State of Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, 1996), fig. 1.

It is not unusual for those digging holes in Middle Tennessee to uncover pieces of the deep past. Historical documents from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries record what seems to be a near-continuous stream of encounters with ancient remains. Those range from accidental fossil discoveries such as the Shumate Mastodon to deliberate excavations of ancient Native American sites by antiquarian scholars from the likes of Harvard’s Peabody Museum. In the middle of that spectrum fell the interested public of Nashville and Middle Tennessee, some of whom spent their leisure time collecting fossils or digging up Native American sites in search of artifacts and curiosities. This trend continues today, as Nashville’s growing population and associated development expand throughout Middle Tennessee and spur both formal archaeological studies and accidental encounters with the past.

During the first decades of the twenty-first century there have been occasional, brief peaks of public interest in our city’s deep past. These are typically in response to ancient Native American sites being threatened or impacted by development efforts, such as the large May Town Center project proposed for Bells Bend in 2008, or construction of the new Nashville Sounds stadium in 2014. For the most part, however, the city’s ancient past has remained a mere footnote to its antebellum and more recent history.

Aside from the good work of the Tennessee State Museum and occasional roadside historical markers, the popular interpretation and treatment of ancient Nashville has been driven mainly by curiosity and imagination rather than modern science. Without the benefit of responsible, accessible sources, explanations of Nashville’s deep past have over the years included tales about lost races of giants and pygmies, various ancient Old World cultures, and “the Moundbuilders,” an outdated nineteenth-century term for the Native Americans who created North America’s first monumental architecture. On the other hand, sources written for schoolchildren, and those for a more general public audience, might lead us to believe that the first Europeans arrived on the banks of the Cumberland River in the late seventeenth century to find a pristine landscape, inhabited only by herds of bison and boundless nature, entirely untouched by human hands.

Just three short centuries before Illinois lieutenant-governor-turned-fur-trader Timothy Demonbreun set foot at Sulphur Dell, Native American communities belonging to what archaeologists identify as the Middle Cumberland Mississippian culture lived throughout the Cumberland River watershed in Middle Tennessee. The French Lick area, today home to Bicentennial Mall State Park and the Nashville Sounds baseball stadium, was the site of a densely populated town. Homes, private and public spaces, cemeteries, and salt processing areas filled the valley of Lick Branch, while an earthen mound built near the river would later serve as the foundation for the French fort and fur trading post.5 On the opposite bank of the Cumberland, in the area where Top Golf now stands, a series of earthen mounds held ritual structures and the homes and graves of high-status individuals. The large village that surrounded those mounds extended north toward Cleveland Park and east along the river toward Shelby Bottoms. These sites were not isolated, but were part of a tapestry of towns, villages, and farms that stretched for miles across the Nashville landscape and into neighboring Williamson, Sumner, and Cheatham Counties.

Just as they predate the French arrival in Nashville, Mississippian period sites do not represent the first human presence in Middle Tennessee. Rather, the archaeological roots of Music City include the entire scope of human activity in the region, extending at least 13,000 years back to the last ice age. The paleontological record of Nashville extends even further, reaching millions of years back into geologic time. It is this cumulative layer-cake of history, the stories told by fossils and artifacts, by sabertooth cats and Native American communities, on which modern Nashville is built.

The First Nashvillians

The first people to set foot in Middle Tennessee arrived in the Cumberland River Valley approximately 13,000 years ago. Over ensuing millennia those ancient Native Americans and their descendants left behind a record that archaeologists divide into four broad cultural periods: the Paleoindian, Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippian. No system of writing or record keeping has survived from this archaeological past. We do not know how these communities identified themselves, what language(s) they spoke, or what names they gave to their towns and settlements. Instead, the four archaeological periods are separated from one another based on gradual culture changes including shifting artifact technologies, diets, settlement types, and social organization.

The Paleoindian period begins with the arrival of the first people in North America, during the end of the Pleistocene geologic epoch. These settlers are known to archaeologists as the First Americans, and as their descendants arrived along the Cumberland, gradual climate shifts accompanying the end of the last ice age had begun to accelerate. The resulting environmental changes impacted both plant and animal communities and contributed to the eventual extinction of large, cold-adapted animals known as megafauna. Nevertheless, the first Tennesseans shared the late ice age landscape with, and sometimes hunted (or not, as we’ll see in Chapter 3), now-extinct creatures such as the mastodon.

Following the retreat of Pleistocene glacial ice, Earth transitioned to the Holocene, our contemporary geologic epoch. From about 8000 through 1000 BC, numerous Archaic period groups inhabited the greater Nashville landscape. The area’s population increased dramatically during this time, as bands composed of multiple extended families hunted and foraged along the rivers of Middle Tennessee. Native Americans also began to experiment with food production over the long span of the Archaic period. They domesticated plants including squash, sunflower, and goosefoot, and as described in Chapter 4, perhaps managed freshwater shellfish beds in the Cumberland and its tributaries. These groups also took part in long-distance trade networks and began to acquire objects from outside of Middle Tennessee, such as artifacts made from large whelk shells originating along the Gulf of Mexico.

The Woodland period follows the Archaic, as between about 1000 BC and AD 1000 Native American communities gradually settled into long-term villages and began to practice household gardening and intensive horticulture. During the Woodland period the construction of earthen mounds, use of ceramic vessels, and bow and arrow technology, all of which developed elsewhere in North America thousands of years earlier, gradually became widespread throughout Tennessee. It was also during this period that Native American groups began to organize into socially stratified societies, connected through both trade and ideology to Woodland period communities in other regions, including the Hopewell and Adena cultures of the Ohio Valley.

For reasons that remain unclear, Nashville-area populations seem to have dispersed during the Woodland period. People continued to live along the Cumberland River and its tributaries, but with just a few exceptions, major occupations in Middle Tennessee shifted south to the Duck River watershed. The principal exception to this trend was the Glass Mounds site, located in Williamson County west of Franklin. That site along the West Harpeth River once included multiple earthen mounds, and based on artifacts recovered during the late nineteenth century appears to have had direct connections to, or major influence from, the Hopewell culture of the Ohio Valley.6 The Glass Mounds site was almost entirely destroyed by phosphate mining during the mid-twentieth century, and Woodland period Nashville remains poorly understood.

By the eleventh century AD, Native American societies in the Nashville area and throughout the Eastern Woodlands transitioned into highly ranked communities of the Mississippian period. In Chapter 5, we describe the Mississippian settlements that flourished along the rivers of Middle Tennessee between around AD 1000 and 1475. The Mississippian period is perhaps best known today for its large towns, in which homes and cemeteries were organized around groups of earthen mounds that, depending on their design, served both living and deceased members of the upper class.

Skilled Mississippian artisans produced beautiful and enduring objects in ceramic, stone, and shell, for both everyday and ritual use. Trade networks, along with political and religious influences, connected the Middle Cumberland Mississippian culture to Native American societies throughout eastern North America. Mississippian period people continued to fish, hunt, and gather wild resources, but primarily made their living by intensive farming of maize, beans, and other crops. Mississippian culture ended in Middle Tennessee during the mid-fifteenth century following decades of droughts and political upheaval. Although a number of Native American tribes continued to periodically enter the region after that time, archaeological evidence for permeant human occupation in greater Nashville is virtually absent between about AD 1475 and the late seventeenth century.

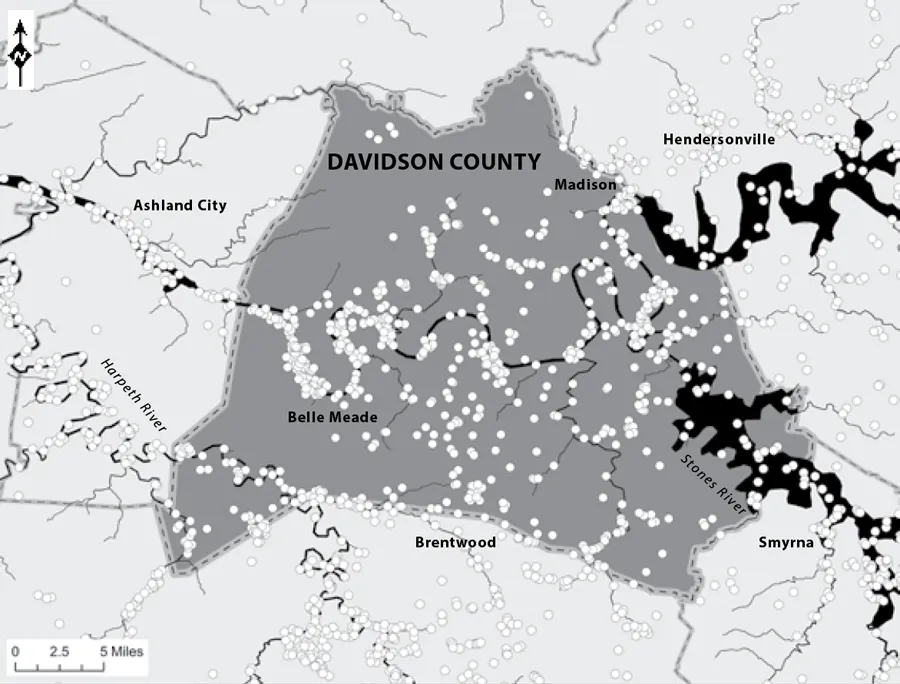

In accordance with federal and state laws, the Tennessee Division of Archaeology maintains a database of known archaeological and paleontological sites within the borders of the state. As of spring 2021, there are nearly 700 site locations officially recorded in Davidson County (Figure 1.2). More than 480 of these include artifacts or fossils originating before AD 1500 and are considered prehistoric. This term is not a value judgement as to the complexity of ancient Tennesseans, but instead means simply that these sites predate the arrival of written texts in the American Southeast.

FIGURE 1.2. Map of archaeological and paleontological sites in and surrounding Davidson County.

Beyond Davidson County, the overall number of prehistoric sites in the greater Nashville area includes more than 330 in Williamson County, over 200 each in Rutherford and Sumner Counties, and around 180 in Cheatham County. These numbers do not reflect the sum total of prehistoric sites in Middle Tennessee, but rather those which have been officially recorded with the Division of Archaeology. “New” sites are constantly encountered as suburban growth expands into previously rural lands throughout the Nashville area. In Davidson County alone, more than thirty sites were recorded between 2015 and 2020.

How Archaeologists Learn about the Past

The archaeological record of Nashville includes all of the evidence of at least 13,000 years of human culture, beginning at the level of the individual artifact. Public interest in ancient Native American artifacts typically focuses on those objects that are collectible, or displayed in museums: whole stone tools, ceramic pots, statues, and artwork. For archaeologists, however, artifacts include every single object modified or used by humans, from the most intricately carved shell pendant to the smallest microscopic plant remains. Beyond these materials the archaeological record also includes features, which mark past human activities and are sometimes defined as “non-portable artifacts.” At the functional level, features include things like hearths or ovens, graves, and the remains of structures. Artifacts and features combine to create archaeological sites, which in turn combine to form human-made landscapes such as the Middle Cumberland Mississippian occupations of Middle Tennessee.

Artifacts and fossils are not the same thing. While artifacts are the result of human activity, fossils are the petrified remains of once-living creatures. Throughout human history, people have encountered and collected fossils, sometimes altering or adapting them for use or display. As a result, those fossils also become artifacts. As with the First American Cave site described in Chapter 2, fossils and artifacts are sometimes found at the same locations, and their stories become intertwined. Ultimately though, they are different things, represent different parts of the past, and are studied by different scientists. Archaeologists don’t dig dinosaurs, although we sometimes get to excavate a sabertooth cat or ice age elephant.

Nashville’s deep past is constantly under threat of destruction by both natural and human forces. Floods, erosion, farming, development, artifact collecting, and even archaeological excavation all destroy sites. Every hole dug and every artifact or fossil taken away from its original setting without a record of its provenience—the exact location where it was recovered relative to the overal...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Making Sense of Nashville’s Deep Past

- 2. The Nashville Cat

- 3. Furry Elephants and the First Nashvillians

- 4. Modern Floods and Ancient Snailfishing on the Cumberland River

- 5. Earthen Mounds Meet Urban Sprawl

- Nashville-Area Learning Opportunities and Further Reading

- Notes

- About the Authors