- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching English Language Learners

About this book

Teaching English Language Learners in Mainstream Classes addresses English language learning (ELL) pedagogical practices and will be particularly useful for mainstream teachers who have limited experience working with EAL/D (English as an additional language/dialect) students. It begins by considering general ELL and EAL/D theory and later examines specific theories in the areas of oracy, reading and writing. Many examples in the book are illustrated with authentic and recent student work samples. This book also helps readers to plan an effective ELL program for the diverse needs of English language learners.

Information

CHAPTER SEVEN

ROLE TO COMMUNICATE LEARNING ENGLISH

When you have to use your imagination, you can think up better ideas ... so when you think, you must be learning English. (10-year-old EL learner)

It [drama] helps you communicate your thoughts because you can feel the situation, and you have more opinions because you take on that role. (11-year-old EL learner)

For some students, taking on the role of another person gives them the opportunity for sustained talk (and then often reading and writing) because it allows them to take a safe risk. If they make a mistake, it is the character who makes the mistake and not them. If they say something that really is from the heart, again it is the character and no-one else need know that it really is their thoughts, as explained by one 11-year-old boy, who said, I like drama ‘cause you can say things that are you, but nobody has to know because you are acting someone else. It is for this reason the chapter is titled ‘role to communicate'.

Drama and language learning

As discussed in previous chapters, to move beyond conversational language and acquire academic language proficiency (Cummins, 2008), students need to be exposed to and then practise a range of registers and language functions. Within a classroom program, providing authentic and believable situations for practising such a range is important. This is why ‘role play’ is often a suggested strategy. For example, in quite a few units of work on the 1850 Australian Gold Rush, role playing miners digging for gold is a suggested activity so that students can simulate (role play) the methods for extracting it.

Such activities may well be useful but they often remain at the level of what I term ‘open ended simulations'. Open ended simulations differ from drama because they usually miss one of the most important components of drama. For drama to be drama, there needs to be a plot, a complication, some tension. When simulations become drama there is far more material to work with and hence talk about. So, for instance, the example of simulating miners digging for gold can become drama if the situation was that miners (without a licence because they could not afford it) were panning for gold when a trooper arrives asking for their licence. This provides some dramatic tension. The focus, and so the themes explored, would therefore be hardship, justice, and so forth. Nevertheless, assuming a role (as for example a miner or trooper) is difficult for many students and especially as students get older, some feel inhibited and embarrassed.

In this chapter we will explore how to set up structures for these students to take risks and feel safe and confident, because drama can enhance language and literacy development (Crumpler & Schneider, 2002; Fleming et al, 2004; Ewing, 2010; Kao & O'Neil, 1998; Stinson, 2008); but, as Stinson stresses, 'one of the main aims of a drama class is to give students something to talk about and a safe physical, cognitive and emotional space to figure out the best way to express their ideas’ (Stinson, 2008: 194).

Readers’ Theatre

Readers' Theatre (RT) is the oral reading of a narrative or poem. It is a drama form that supports students’ reading comprehension, fluency and critical literacy. At the same time it helps students understand the elements of drama such as pace, tone, expression and gesture. Performance of RT connects talking and listening skills with reading and writing. The process of turning narrative prose into dramatic script gives students an insight into the technical choices authors make. When involved in RT, students are actively engaged in analysing a text, but they do so from within it. That is, by taking on the roles of the characters and enacting the author’s choice of language, students become text participants. As well, students gain an insight into the author’s point of view and hence analyse how this text positions them as the reader (text analyst). This can be a very powerful outcome. In one Year 5 class, for instance (Hertzberg et al, 2006), several groups of students in the Developing English phase, were preparing a Readers' Theatre for an excerpt from I am Jack (Gervay, 2000). The students debated the tone of voice the mother should use. Was she cross with Jack or was she just trying to appeal to him to be patient? There were varying opinions across the groups and these different interpretations were portrayed through their RTs. These variations were viewed and then discussed and debated (text analyst). Furthermore, because students needed to reread the script at least several times before presenting their interpretation, they were repeating and therefore practising a good model of English.

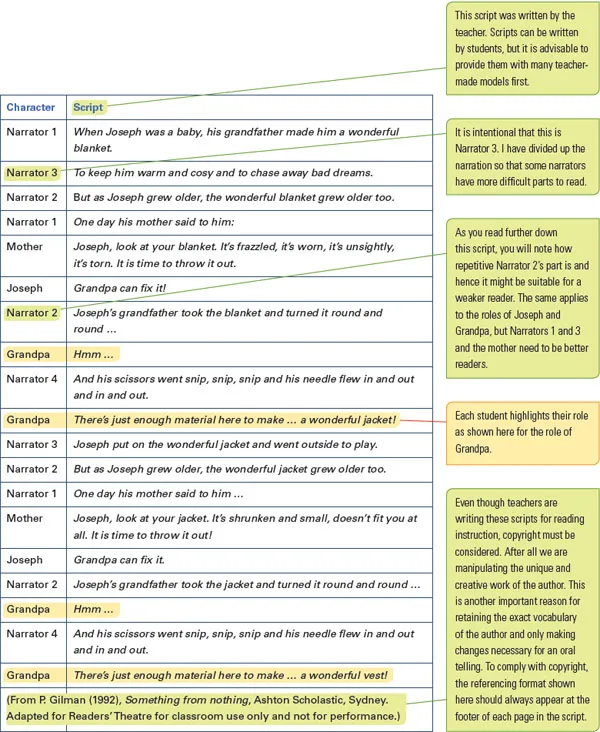

Making RT scripts

Texts with a lot of dialogue are best and the text is adapted to make it suitable for performing as an oral reading. For instance, indirect speech might be altered to direct speech (making it a good way to explore the concepts of first and third person) but the original meaning and the vocabulary used by the author is retained. For example, the text 'What great big ears you have! said Little Red Riding Hood’ in the narrative, would be altered so that ‘said Little Red Riding Hood’ is deleted because, when performing it, Little Red Riding Hood is speaking these words. At times the narrated text might be divided and allocated to different readers.

The excerpt of a RT script is demonstrated below.

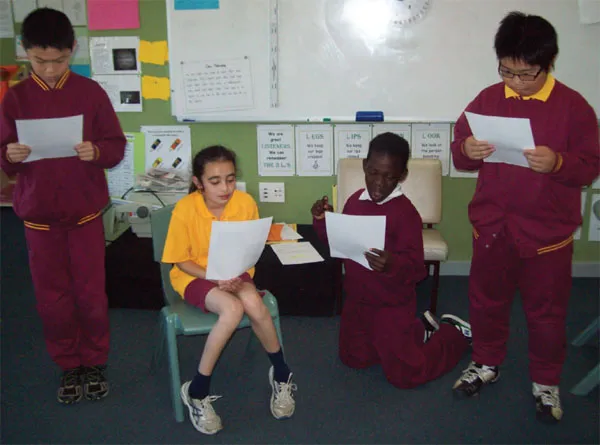

Staging Readers’ Theatre

In RT, performers remain ‘on stage’ for the duration of the reading, and they read the script rather than memorise lines. In addition, there is minimal stage movement by performers, and they face the audience as they read the story, as can be seen in Figure 7.1.

While RT can be rehearsed and refined to include stage sets and costumes, I usually do not include these, or keep them to a minimum. The reason for this is twofold. First, costuming can detract from the purpose of RT, which is to use the drama skills of, in particular, voice, gesture, levels and space to tell the story. Second, and more importantly when using RT for English language learning, the organisation of costuming and props becomes an additional drain and strain on teachers’ time. As a result, and understandably, RT might then not be used routinely for enhancing English language learning.

Figure 7.1

Readers' Theatre in progress

The Readers' Theatre instructions that students can use when preparing their RT are shown below.

1 Decide on your roles and highlight your part.

2 Practise reading the script together.

3 As you practise, think about the following aspects and as a group decide on:

Verbal expression: How will you speak your part?

• tone (eg happy/sad)

• volume (eg loudly/softly)

• pace (eg quickly/slowly)

Body language: What sort of expressions will you have? What sort of gestures?

• facial expressions

• hand and other body gestures.

Position: What position will you take when you read your part? (In Readers’ Theatre you do not move very much, and you face the audience.)

• Where will you stand or sit?

• Will you alter your position at tlmes?

Sound effects: Do you need sound effects? If so, which?

• Do you want to use some instruments for sound effects?

• Do you want to use body percussion?

© Margery Hertzberg, 2009.

Using RT as an oral reading strategy

As discussed in Chapter 5, oral reading is a difficult skill, but it is beneficial because students both articulate good models of English and practise pronunciation. However, reading aloud can be an intimidating experience for many students and also on a first reading many students just decode as opposed to comprehend.

These sentiments were confirmed by an eleven-year-old EL learner in the Developing English phase, who said

Well, the first time I'm not reading really good with people. The first time I mean I get embarrassed, but not when I've done it lots of times and with my friends. When we do Readers' Theatre, we read it [the script] heaps of times and so then I can read the words and understand what the story is about. Usually I just read the words but I don't know what I'm reading.

Another EL learner put it this way:

You don't feel stupid if you make a mistake because they all know you're only practising and it’s not like the whole world is going to see it.

For more information on how to make scripts and for examples of scripts, go to the PETAA website: www.petaa.edu.au.

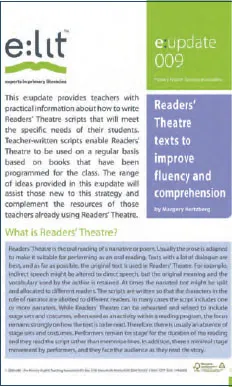

Figure 7.2

This article on the PETAA website, describes Readers’ Theatre in more detail.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to detail the aspects of drama in-depth, and readers are referred to Ewing et al (2004) for more information.

Readers' Theatre is but one form of drama that encapsulates why drama is such an important part of a student’s English language learning education. The emphasis in the rest of this chapter is on a type of drama termed educational drama.

Educational drama

At the core of ‘educational drama’ is enactment. The phrase ‘walking in someone else’s shoes’ is often used to describe this feeling. The emphasis is not about acting someone else, it is about being someone else and explicitly attending to the drama elements of gesture and facial expression, space and levels, verbal expression, sound and silence. And as stated previously, for drama to be drama as opposed to simulation there needs to be a problem - some tension which addresses an underlying focus (theme) to be explored. Often an object, or repeated word or movement throughout the enactment will act as a symbol.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to report on all the findings and readers are referred to Hertzberg (2004b), Hertzberg et al (2006) and FGT (in progress). In summary though, the conc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- ONE Language learning and language use

- TWO Who are our English language learners?

- THREE Pedagogical conditions for learning a language

- FOUR Focus on oracy

- FIVE Focus on reading

- SIX Focus on writing (written by Janet Freeman)

- SEVEN Role to communicate: Learning English through drama

- Conclusion

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Teaching English Language Learners by Margery Hertzberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.