- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designing learning for diverse classrooms

About this book

Designing Learning for Diverse Classrooms explores practical teaching principles, supporting teachers in the design of meaningful and challenging learning that ensures productive access for all children. It uses a wide range of interactive tasks to highlight the importance of whole-class talk and show how it can assist children to engage with intellectually challenging activity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

LEARNING AT HOME AND AT SCHOOL

Interaction with other people assists children in their development by guiding their participation in relevant activities, helping them adapt their understanding to new situations, structuring their problem-solving attempts, and assisting them in assuming responsibility for managing problem solving.

(Rogoff, 1995: 93)

THE BEGINNINGS OF INTERACTION

Aidan Macfarlane (1977), a paediatrician interested in the psychology of childbirth, recorded the immediate talk of midwives, mothers and fathers at the birth of a child. As might be expected, there was talk about the baby: its sex, its weight, its hair colour and its wellbeing. What might be less expected, given that the baby cannot yet talk, is that there was also talk to the baby. The parents greeted their baby – "Hello!"; gave commands – "Open your eyes then."; asked questions – "What are you looking at me like that for?"; sometimes answered for the child – "What colour are your eyes? Blue, she says."; and directed comments to the child – "Oh, you're nice. That's a lot of noise for a little girl. That's right – you've opened your eyes. That's lovely."

So, from the earliest moments we begin the process of assisting our young to live culturally. We do not wait until they can ask us a question about the world before we begin to engage them in the world. From a slightly different perspective, it is interesting to note how we 'teach/engage' our children at a point beyond their capability. In Macfarlane's example above, this is clearly seen by the parents both asking and answering a question directed at the child.

PEEKABOO

It is not very long before children will begin to participate with those around them and, as they do so, parents and others keep a step ahead of the child's development – they 'raise the ante' (Cazden, 1979) in terms of interaction and task demands. The game of peekaboo is a good example of this.

Peekaboo and other variations of appearing/disappearing games, while not universal, are nevertheless extremely common across diverse cultures and are played regularly by parents and their infants (Fernald & O'Neill, 1993). Some common features between a Xhosa mother, a Tamil mother, a Portuguese mother, a Greek mother and a North American mother of European descent include exaggerated vocalisations, especially at the exciting part of the game, exaggerated facial expressions on the part of the mother expressing her own enjoyment, and the maintenance of eye contact. Another interesting feature is the degree of assistance given to the child as they learn to play the game. At around four months, a mother will typically move her face in and out of her infant's view, or move up close to get attention, move back and then 'loom' toward the infant's face with an accompanying vocalisation.

Not long afterwards, the disappearance element comes into the game, and the more familiar stages of attention getting, followed by hiding, followed by reappearance (Bruner, 1975) become regular features. Early on, however, it is the mother who does the hiding (either herself or the child), so that while the cognitive challenge of the game has increased from the 'looming' period, the child is still assisted in its execution. Somewhere between eight months and fifteen months the child begins to take over the role of the 'hider', and it is at this point that the end of peekaboo as a mutual activity between mother and infant draws near.

It draws near because the child no longer needs the mother's assistance, or scaffolding, to grow linguistically and cognitively in this developmental area. As Cazden (1979: 11) has noted:

Variations in the games over time are critical: the adult so structures the game that the child can be a successful participant from the beginning; then, as the child's competence grows, the game changes so that there is always something new to be learned and tried out, including taking over what had been the mother's role. When variations are no longer interesting, the game is abandoned and replaced.

There is a mutuality about this process: on the one hand the mother 'hands over' as much of the interactive 'work' as the infant can handle, and on the other there is a passion to 'take over' on the part of the infant. Games like peekaboo might serve then as a useful metaphor for our interactive work with children and young people. We need to engage children with the required challenging performance; we need to assist their participation (as if they can already play); we need to be enthusiastic about the interaction; crucially, we hand over roles (van Lier, 2001) as soon as they can be taken up; and, once mastered, we move on to the next developmental level.

AFTER PEEKABOO

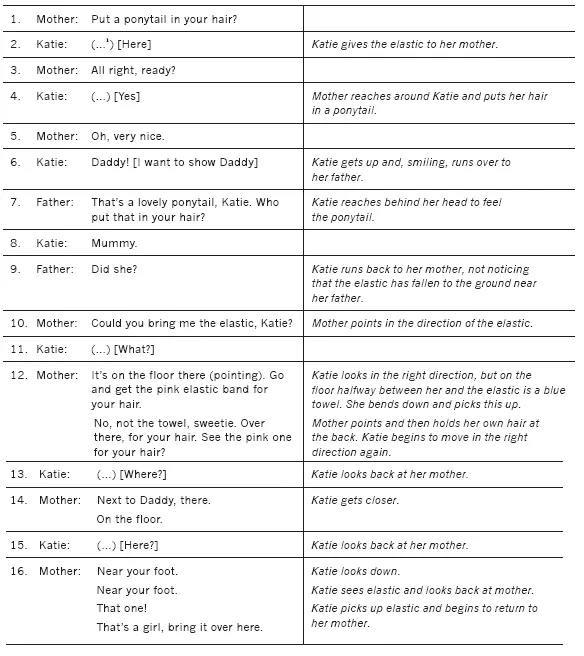

In the following interaction, my daughter Katie, who at this stage had only a two-word vocabulary ('Mummy' and 'Daddy') and yet had moved out of the peekaboo stage, brings a pink elastic band to her mother, who is sitting on the floor in the lounge room, to have her hair put in a ponytail. She sits on her mother's lap, facing her, with the pink elastic in her hand.

Interaction 1: Learning to perform in the world with assistance

In this interaction, Katie is given a task (it is handed over) that is beyond her – "Could you bring me the elastic?". Katie indicates she doesn't know what is meant, so the mother scaffolds, or assists the performance, by adding: "It's on the floor there (pointing). Go and get the pink elastic band for your hair". This extra information is concrete (on the floor), includes pointing, and is rephrased as a clearer direction, "Go and get". Katie sets off, but doesn't succeed because she picks up the towel instead. The mother then offers more assistance by naming the towel, continuing to point in the right direction, and adds further assistance by holding her own hair in an imaginary ponytail. Katie gets closer, and the mother adds more by now indicating colour, "See the pink one for your hair?". Katie asks for further directions, and the mother now narrows the focus by telling her it's near her father and on the floor. By now Katie is pretty close. She checks with her mother, who responds by telling her it is near her foot. Katie picks up the elastic and returns to her mother.

SOME FEATURES OF LEARNING TO PERFORM IN THE WORLD WITH ASSISTANCE

Without wishing to read too much into this small interaction, it is worth pondering on some of its instructional features. First, the task is a challenging one for Katie. She is capable of doing it – but not without assistance. In other words, the mother is not engaging her daughter at a developmental point where she is but at a point where she is not yet. Second, she gives assistance when needed, but calibrates this assistance to ensure Katie's continued performance – a kind of frustration management. Third, when errors are made – for example, picking up the towel – they are pointed out explicitly and further assistance given. We can't say with any certainty whether Katie has learnt new vocabulary items (and they would be probably at a receptive level in any case), or learnt the way that commands are sometimes phrased as questions ("Could you bring me the elastic?" versus "Go and get the pink elastic band for your hair."). It seems to me, however, that we can say that Katie is learning something about herself as a member of this group. She is learning to see herself as someone who is expected to do things that are challenging; that she will receive assistance to do these things; and, crucially, that she has a dialogic role to play in pursuing successful outcomes. Through dialogue, she is continuing to build a model of the world that is intersubjective – she is learning to "read other minds" as Bruner (1996) puts it. Tasks such as these, for both young and not-so-young children and adults alike, are the fuel for cognitive, linguistic and social development.

FROM HOME TO COMMUNITY: LEARNING SOCCER

Over the past few years, in winter, I usually find myself watching children play soccer in a local competition. Apart from excursions into the world with family, sport is often one of the first times a child participates individually in a broader community. In this context, my interest is drawn to how the learning of soccer is carried out over the course of a young player's career.

The beginners are easy to pick. They are the ones where generally both teams form a large, massed group on the field, all chasing the elusive ball – a style of play that was once labelled by a Sydney journalist and father as 'magnet ball'. What's interesting for me, however, is the assistance given to these novice soccer players. Task constraints take the form of playing on a much smaller field than normal. Each novice team has only eight rather than eleven players. The time for each half is less than normal. Assistance for success is further given by coaches being allowed on the field to run with their teams and point the kids in the right direction. The goalkeeper's father or mother is allowed to stand next to the smaller-than-normal goal to guide their child's performance. From an instructional perspective, the coach's teaching is proleptic in orientation. In this context, prolepsis means that the coach presupposes the children understand soccer as a "precondition for creating that understanding" (Cole, 1996: 183). Likewise, parents take a proleptic orientation with their newborns – they assume understanding as part of the process of the children learning to talk. In the soccer example described above, however, this proleptic orientation is supported by various 'scaffolds' designed in such a way to ensure the novices can play soccer successfully. Over the next few years these scaffolds are gradually removed, until by adolescence the players are pretty much playing the adult version of the game.

This out-of-school learning is specifically designed for success. Part of this common-sense process of everyday learning and teaching is the belief that you will learn soccer by playing it. The material to be learnt, in other words, has to be 'handed over' to the learners. But there is also the realisation that handover is not sufficient. Most will not learn soccer (or like it) without assisted performance.

In a similar vein, Childress (1998), an ethnographer, spent a year observing adolescents in their high school setting and in their broader community settings. What puzzled Childress was the frequency with which the students told him about the boredom of school and how one boy, who was considered an "archetypal slacker" at school, was a competent performer in a wide range of other kinds of learning tasks out of school. And he was not the only one. This le...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: LEARNING AT HOME AND AT SCHOOL

- Chapter 2: A SOCIOCULTURAL PERSPECTIVE ON LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT

- Chapter 3: GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR DESIGNING LEARNING

- Chapter 4: EXPANDING TALK ROLES IN THE CLASSROOM

- Chapter 5: INTRODUCTION TO INTERACTIVE TASKS: CROSSWORDS AND FLOW CHARTS

- Chapter 6: INTERACTIVE TASKS: RANKING, SEQUENCING AND TOPIC OVERVIEWS

- Chapter 7: WORKING WITH WORDS AND TEXTS

- Chapter 8: BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER

- Endnote

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Designing learning for diverse classrooms by Paul Dufficy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.