- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Industrial Catalysis

About this book

Industrial Catalysis provides an excellent introduction to catalytic principles and processes, addressing the applications of inorganic-, organic- and biocatalysts in industrial chemistry. Each chapter is focussed on one catalytic process and discusses its life cycle from source materials, catalyst synthesis, the catalytic process, lifetime and recovery. The book also includes a comprehensive overview on industrial processes employing catalysis.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Catalysis

The acceleration of a chemical reaction by some chemical that is itself not consumed in the process has been the working definition of catalysis for over a century. It is probably not a coincidence that the development of catalysts roughly parallels or follows the expansion of the Industrial Revolution. This revolution brought with it not only the larger scale production of commodities than had ever been accomplished before, it also coupled the production of commodities to making money and the creation of wealth. Prior to this, civilizations had flourished using what can be called cottage industries to make virtually all end products. For example, smelting and working metals for the production of coins, tools, armor, and weaponry was a large enough enterprise in the Roman Empire that its aerial pollution and effluents appear to have in some manner polluted a large swath of Europe, and left a trace in even the Greenland ice cap. But this was the result of more individuals working at trades – again, cottage industries – and not the mechanization of any processes. During the Industrial Revolution, trade over larger areas than had ever been seen before meant that larger amounts of materials, commodities, and end products were needed. That in turn meant that less expensive methods of making materials were required. As the nineteenth century turned to the twentieth, this in turn began to mean that the use of a catalyst to produce a product was economically advantageous.

As any chemical field blossoms, there are eventually names associated with some portion of it, often with a specific advance or a specific reaction. In the case of catalysis, one scientist who can be considered the father of the field is Vladimir Nikolayevich Ipatieff. Born in Imperial Russia in 1867, Ipatieff became important to the Czar’s war effort in the First World War, realized that the political environment had become extremely dangerous by the end of the 1920s, and ultimately emigrated to the west in 1930. Toward the beginning of what became a long and fruitful career, he noticed that some reactions proceeded much more quickly in steel containers than they did in glass – the first mention of a serendipitous catalysis. Later in his career, working at Universal Oil Products (UOP), Ipatieff led teams that produced numerous catalysts, some of which are still in use today. While Professor Ipatieff’s name is unfortunately not well known or remembered among the general population, or even chemists, today, he did leave a lasting legacy. His work with UOP was fruitful enough that the company made a significant endowment to the American Chemical Society, which was used to present the Ipatieff Prize every 3 years. From its first presentation in 1947, the prize has become an impressive list of some of the greatest researchers in the field of catalysis.

1.2 Reaction chemistry

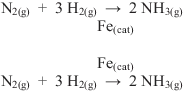

Curiously, despite the growing use of catalysts over the course of time, and despite the standardization of what we now think of as basic reaction chemistry, there has never been a standardized, uniform way to represent a catalyst in a written chemical reaction. Figure 1.1 shows the two means by which a catalyst is normally indicated in a reaction, above or below the reaction itself. Note that some professionals will debate whether or not a subscripted indicator like “(cat)” is necessary, while others will insist that one of the two representations is the only official or correct one. But the fact remains that a catalyst is often represented in one of these two ways, but may also be represented by other means as well. It is also noteworthy that the state or conditions of a catalyst cannot be easily represented in a reaction. Again turning to Figure 1.1, it is not known whether the iron catalyst is a powder, a foil, or a material on some support.

Figure 1.1: Representations of a catalyst in a reaction.

As well, almost universally, while the presence of a catalyst is shown in written reactions, the conditions under which it operates are not. Does the catalyst reduce the working temperature of a reaction, for example? While that is a generally favorable reason to use a catalyst, temperatures are not routinely mentioned in written representations of reactions. Does the catalyst only function under high pressure and high temperature (albeit, lower than the un-catalyzed reaction)? Again, this is not always shown in a written representation of a reaction, although it can be placed above or below a reaction arrow as well. The means by which a catalyst and reaction conditions are represented continue to have no standardized type of notation.

1.3 Catalyst production

The production of catalysts, as opposed to their uses, is the main focus of this book. We must arrange it by the chemical product, or by the chemical process, being discussed, but the main idea and focus is always, how is the catalyst itself produced? The answer to that question is not only a matter for and of corporate research but is the main thrust of numerous national and international societies [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

Table 1.1 is a non-exhaustive list of major catalyst producing companies. Note that some of the names are rather common to chemists and c...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Homogeneous catalysis

- Chapter 3 Heterogeneous catalysis

- Chapter 4 Acrylics

- Chapter 5 Adipic acid

- Chapter 6 Ammonia

- Chapter 7 Ammonium sulfate

- Chapter 8 Benzene, toluene, xylene (BTX)

- Chapter 9 Butadiene

- Chapter 10 Caprolactam

- Chapter 11 Chlorine

- Chapter 12 Cumene

- Chapter 13 Cyclohexane

- Chapter 14 Ethanol

- Chapter 15 Ethylene

- Chapter 16 Ethylene dichloride

- Chapter 17 Ethylene glycol

- Chapter 18 Ethylene oxide

- Chapter 19 Formaldehyde

- Chapter 20 Hydrogen

- Chapter 21 Hydrogen peroxide

- Chapter 22 Isopropanol

- Chapter 23 Linear alpha olefins

- Chapter 24 Methanol

- Chapter 25 Nitric acid

- Chapter 26 Nylon

- Chapter 27 Phenol

- Chapter 28 Phosgene

- Chapter 29 Polycarbonate

- Chapter 30 Polyester, polyethylene terephthalate (PETE)

- Chapter 31 Polyethylene

- Chapter 32 Polypropylene

- Chapter 33 Polystyrene

- Chapter 34 Polytetrafluoroethylene

- Chapter 35 Polyvinyl chloride (PVC)

- Chapter 36 Propylene

- Chapter 37 Propylene oxide and propylene glycol

- Chapter 38 Rubber

- Chapter 39 Styrene

- Chapter 40 Sulfuric acid

- Chapter 41 Toluene diisocyanate

- Chapter 42 Vinyl acetate

- Chapter 43 Vinyl chloride monomer

- Chapter 44 Vitamins

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Industrial Catalysis by Mark Anthony Benvenuto,Heinz Plaumann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.