- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

On November 11, 2000, a train caught fire in a mountain tunnel at the Kaprun ski resort in Austria, killing 155 people. The disaster and its aftermath traumatized the nation. This in-depth account by authors Hannes Uhl and Hubertus Godeysen brings the events to life and reveals the astonishing incompetence and corruption that led to the accident and undermined the subsequent trial. 155: The Kaprun Cover-Up serves as a warning to people in every country about threats to public safety and the rule of law.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Kaprun, summer 1994

"What a mess," says the hydraulic technician, lying on his back and looking through a small hole at the legs of two electricians above him in the attendant’s compartment. "How am I supposed to lay pipes here?"

The only answer from above is unintelligible muttering.

This isn’t how Hans Unterweger had imagined his day. For weeks, he’s been working in Kaprun on the undercarriage of the train. With two colleagues, he’s laying hydraulic oil pipes in the steel skeleton. Four independent systems. The job is almost done. The only thing missing is the train itself, constructed that summer less than 200 kilometers away in Oberweis in the Salzkammergut. Today, the giant package arrived in Kaprun, two 15-meter-long trains made of steel, aluminum, polystyrene, and fiberglass-reinforced plastic. Everything is ready. The body of the train should fit right onto the running gear like a lid on a pot.

The old railway on the Schmiedinger Kees (as the glacier on the Kitzsteinhorn mountain is known) is getting on in years. In the 1970s, it was considered a wonder of engineering, connecting seamlessly with the Tauern power plants on the eastern side of the Kitzsteinhorn. The two reservoir dams high in the Alps, Limberg and Moserboden, had become a national legend, a symbol of Austria’s reconstruction after the Second World War.

In 1964, a cable car started taking people to the glacier via the Salzburger Hütte. Skiing boomed at the time of the Wirtschaftswunder, or economic miracle, and often there was no way to cope with the sheer number of visitors. It only made things worse that the cable car couldn’t run during a storm. In that case, the skiers either never made it up the mountain, or they were stuck at 2450 meters. There is a long list of people who thought they could ignore all the warnings and prohibitions, tried to hike down to the valley on their own, and died. There’s no descending path here—just rock faces, slippery, steep meadows, and no place to get a foothold.

The railway, constructed between 1972 and 1974, was supposed to make these problems a thing of the past. The glacier would be open to mass tourism and visitors could travel there and back in any weather. A bold plan—an unprecedented masterpiece. A tunnel 3.3 kilometers long with an average incline of almost 50 percent, and a maximum incline of 57 percent at the top station. The new railway is designed to reach a maximum speed of ten meters per second. That means it would take only eight minutes to go from 911 meters above sea level in the valley to 2450 at the glacier.

So Unterweger, the hydraulic technician, has a big responsibility. He’s doing open-heart surgery on the funicular railway’s safety system. If the cable were to snap and the train started falling down the tunnel, his hydraulic emergency brake would kick in automatically with 190 bars of high pressure, literally stopping the train in its tracks. It could keep a whole herd of elephants from falling.

"Sleek piece of work," he thought when he first saw the new train hanging from the crane. The railway had shed its old image of clunky, angular metal trim for a new signature style of elegant curves. "Check it out—Kaprun is getting up to date!"

Eight minutes to the glacier, in a vehicle that compares favorably with the French TGV or the German ICE. Admittedly, not nearly as fast, but it climbs like a mountain goat. One of the two trains is actually called "Kitzsteingams" ("Kitzstein Chamois"). The other has the rather mysterious name of "Gletscherdrache" ("Glacier Dragon").

That morning, the new Kitzsteingams was positioned precisely to the millimeter on its old steel skeleton. Everything fits—except Unterweger and his hydraulics. In the place where the experienced technician is supposed to lay his measuring line from the chassis to the pressure gauges in the console, there’s no room.

He squeezes out from under the train with a groan, climbs the ladder, and sees the two electricians still standing in the attendant’s cab. They’re whispering, avoiding his gaze.

"Guys, there’s a fan heater in the way where my lines are supposed to go. It’s just sticking out of the console in the cab."

"I know," says one of the electricians, annoyed. "They said there’s enough space for the lines. You just have to route them around the heater."

"I’m supposed to custom design this with a heater in the way?" the hydraulic technician snaps back, "You can’t be serious. I don’t even have room to move around, let alone install pipes."

"Calm down," says the electrician soothingly. "We’ll take the heater out, then you’ll have room to move." He nods at his fellow electrician.

"How did the heater even get there?" asks the hydraulic tech, still indignant. "I mean, right where my lines are supposed to go?"

"They didn’t get the right fan heater at the company in Upper Austria where the train was assembled. So they got this one and sank it into the wall of the console."

"But why sink it in? Every fan heater has a suspension device. You just have to mount it on the wall, without all this taking things apart and screwing them together. And I’d have room for my lines."

"That was the plan, but it didn’t work. If they’d hung the heater up, the attendant wouldn’t have been able to open the door to the cab. So they took it apart and screwed it into the wall."

"Well, bravo," says Unterweger, "Quite a plan you’ve all come up with there."

Chapter 2

In the vast check-in area of Narita Airport in Tokyo, on November 6, 2000, 42-year-old Okihiko Deguchi is waiting near the Japan Airlines counter with his 13-year-old daughter Nao, as well as two girls and two boys, all 14 years old. They got an early start that day in their home prefecture of Fukushima. At about 10:30 in the morning, they’re standing at the meeting point, waiting for the other four members of their group. All of them are looking forward to a week of ski training on the Kitzsteinhorn in Austria.

Okihiko Deguchi is a well-known Japanese professional skier who became a successful trainer and is coaching the five young people from Fukushima. The three girls and two boys, still in junior high school, are some of Japan’s best young skiers and hope to qualify for the Olympics. Fourteen-year-old Tomohisa Saze is already a member of the Japanese representative team and is training hard to be nominated for the World Championships. Ayaka Katoono, also 14, is a member of her prefecture’s youth ski team who would like to qualify for the university team and become a teacher after completing her studies. Tomoko Wakui has two great passions: skiing and fashion. She hopes to become a famous fashion designer someday. Masanobu Onodera is an enthusiastic skier who is still deciding whether to become a professional skier or a computer programmer. And Nao, although the youngest participant, is already a highly talented young skier, her famous father’s pride and joy.

Their plane leaves at 12:50, but they don’t have to wait long: "Hello, Mr. Deguchi! Welcome to Tokyo," says Masatoshi Mitsumoto to the trainer, the five young people and two fathers who came along. He and his 22-year-old daughter Saori had the shortest trip to the airport and brought along one of Saori’s classmates. A few minutes later, Maki Sakakibara also arrives at the meeting point with her boyfriend; at 25, she is the eldest participant. Soon Hirokazu Oyama is there too. He rode in on the airport bus after a heartfelt send-off from his parents at Takasaki bus station. His father works as a manager for Japan’s renowned ski manufacturer Ogasaka and its famous ski team. Ogasaka is one of the sponsors of the group’s training trip to Austria.

Deguchi returns the friendly greeting and introduces the parents to each other; they exchange deep bows. The nine young people are less formal. The girls hug each other happily and the boys go for casual handshakes. Now he has his group together, talking eagerly and finding out what they have in common. Deguchi looks at his wristwatch and suggests they should check in. The Japanese travel group take their bulky luggage up to the counter and hand it in; the trainer gets ten boarding passes.

Before going through security they all turn around once more, wave one last time. The trainer makes a deep bow. Then the airport swallows the little group.

"Let’s go to the observation deck and watch our kids fly away," suggests Masatoshi Mitsumoto. The fathers and Maki’s boyfriend follow him. When they reach the deck, they recognize the plane the group is sitting in. At 12:35 the gangway is drawn back and the plane slowly taxis to starting position. After a few minutes the turbines roar, the Japan Airlines aircraft begins to roll, it picks up speed, the flaps on the wings go up, and at 12:50 on the dot, the plane takes off. They know the passengers can’t see them from in there, but they still wave at the plane with its circular red crane design on the tail fin as it disappears into the clouds. "Itterashai and sayonara!" they call after the young travelers.

On the plane, the three youngest sit together. They’re the most excited because this is their first long-distance flight. Saori Mitsumoto and her friend Ruouko Narahar are also sitting together. They are students at renowned Keio University and belong to its prestigious ski club. Both girls have potential for a great career after graduation—not only are they excellent skiers, they also get very good grades.

Maki is hoping her training on the Kitzsteinhorn will help her qualify for the Japanese ski competitions in January 2001 and become a professional. Later, she would like to become a coach for the Japanese skiing elite. Hirokazu, who wants to become a skiing instructor and dreams of managing a ski hotel, is hoping to improve his technique enough to present the new ski models for Ogasaka. All nine young people are full of anticipation. Once the plane has reached cruising altitude and the seatbelt signs are off, they swamp their trainer with questions about where they’re going and what it’s like to ski in the Alps. But they have a long trip ahead before they can strap on their skis. Because of the eight-hour time difference between Europe and Japan, they’ll have an eleven-and-a-half-hour flight behind them when they reach Copenhagen at 4:30 pm. Their next flight leaves at 5:15 and lands in Munich at 6:55. From there, they’ll take a charter bus to Kaprun, arriving at 10:30 pm.

The nine young Japanese skiers. Photo taken on November 8, 2000 on the Kitzsteinhorn.

On November 10, the phone rings at Nanae and Masatoshi Mitsumoto’s house in Tokyo.

"I just wanted to give you a quick call from Austria," their daughter Saori shouts into her cellphone. The connection is bad, but her parents can understand her.

"We're skiing on the glacier a lot and eating in Kaprun in the evenings, our hotel’s there too. We’re having a good time and tomorrow we’re going up the mountain again. The weather’s supposed to be perfect tomorrow. On the Kitzsteinhorn they’re having the international snowboard opening with a competition, a party, and fireworks."

"We’re glad you’re having a good time, keep having fun! We’re thinking of you. Sayonara," shout her parents—and that’s the end of the call.

The next day, the group from far-away Japan stand close together with their equipment in front of the Kitzsteingams, the Kaprun glacier train, which pulls into the valley station at 8:57 am. A few minutes later, father Okihiko Deguchi nudges his 13-year-old daughter Nao into the train first. He follows with the other eight young people.

Chapter 3

"Rise and shine! It’s an amazing day." Matthäus and Tobi are the first ones up, as always, while the rest are hardly stirring.

It’s just after seven in the morning. Less than six hours ago, the five high-school graduates were still at the kick-off party for the snowboard opening at Kaprun Castle. Thanks to the "ultimate opening package" they bought for 790 schillings, there’s a lot for them to take advantage of this weekend—the lift pass for Saturday and Sunday with all the events on the glacier, like the "Endless Winter Snowboard Test" with more than a thousand of the latest snowboard models, the fun park, a speed-measurement course, jump contest or pipe contest. For these passionate snowboarders from Vienna, it’s an exceptional experience.

This is their first trip together without parental supervision. All five grew up in the same area, the Währing and Döbling districts at the northwestern end of Vienna. Their enthusiasm for snowboarding isn’t the only thing that brings them together. They’re a group of five best friends who took their final exams—the Austrian Matura—early last summer and are ready to begin a new phase in life.

Matthäus Stieldorf, born on July 31, 1982, once wanted to join the Pioneer Corps of the Austrian Armed Forces. An extremely strong and athletic young man, he was looking for physical and technical challenges there. However, his nearsightedness put an end to those plans. Matthäus pivoted to an application for community service, more precisely, Holocaust Memorial Service in Milan or New York. In secondary school, he had spent half a year as an exchange student in North Dakota, where he overcame linguistic and cultural barriers. He felt drawn to faraway places again. But the Ministry of the Interior was skeptical. The fact that a young man would first voluntarily apply for a year in the Armed Forces and then refuse armed service on grounds of conscience was met with suspicion. So he enrolled in law school at the Juridicum in Vienna. He’s following in the footsteps of his father, a highly regarded Vienna business lawyer. His goal is to take over his father’s firm, even though Dad advises against it: "You really want to do that to yourself?" he asks.

Matthäus’ mother Karin is an architect at TU Wien, the Vienna University of Technology. She had put her career aside in order to raise Matti, as his parents call him, and his sister. The Stieldorfs wanted their children to have a good start in life, in a caring family environment. The Theresianum, a Viennese private school steeped in tradition with an emphasis on manners, poise, and an international outlook, put the finishing touches on Matthäus. He got top grades on his final exams without being labelled a nerd. He’s seen as being consistent in everything he does. He knows how to combine confidence with a laid-back attitude. Despite his physical strength, he’s the conflict-avoidant type, deliberately calm and composed, always eager to settle things peacefully. The power he’s gained from martial-arts training in taekwondo and capoeira is something he never brings into play.

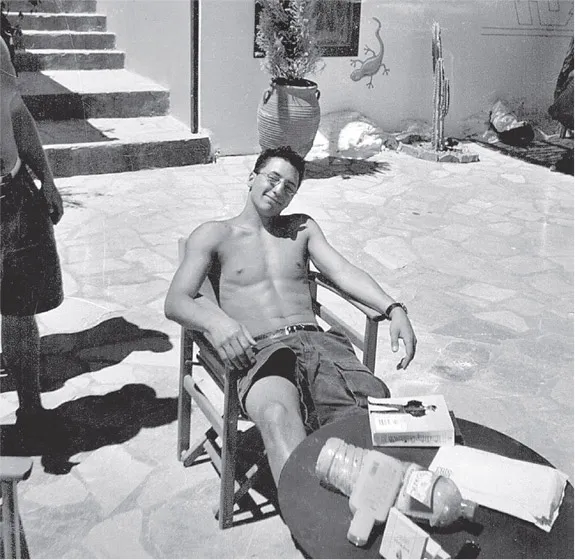

Matthäus Stieldorf in Greece, summer 2000

He was on skis at the tender age of three, which is unusual for a child in the flatlands and hills of eastern Austria. But his parents were from the Tyrol. Skiing trips back home, near Innsbruck or on the Arlberg, were always included in their vacation plans. They also took short excursions to Hochkar in Lower Austria, not far from Vienna. And so the city boy quickly became a good skier. As a young Gymnasium student, Matthäus joined a tour group on the Arlberg and was immediately placed in group 1 with the best. Not long afterwards, he hung up his skis. Now snowboarding is his favorite hobby.

On the skiing vacations their families take together, the boys are now getting their kicks off the beaten track. They’ll make any climb, no matter how long, for a chance to slide down on fresh, untouched "powder." This is where they find true freedom, especially if they can put on a show by making a spectacular jump from the half pipe like the snowboarders they admire.

The five friends have never been on the glacier in Kaprun. They set off Friday afternoon. Franz’s parents have lent them a roomy van that fits all their snowboards and luggage for the weekend and should give them a safe ride on the Autobahn. Matthäus packs his things at his parents’ house in the Sievering neighborhood of Vienna. His father is spending the day with the Lions Club at a wine-tasting in southern Styria. His moth...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Prologue

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Chapter 37

- Chapter 38

- Chapter 39

- Chapter 40

- Chapter 41

- Chapter 42

- Careers

- The victims of Kaprun

- Photo credit

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access 155 by Hannes Uhl,Hubertus Godeysen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.