![]()

CHAPTER I

THE PEOPLE AND THEIR VILLAGE

WINTER had begun. The first snow of the year had fallen. It covered the muddy streets of the village, softening the nakedness of the fruit trees which stood lonely in the bare yards. The wind from Mount Vitosha came whistling down the empty lanes, sending both man and beast to seek protection and warmth. The animals huddled in their thatched folds and shelters; the women and children crowded on the little stools near the fireplace at home. The fall sowing of wheat was in. The fields, wind-swept and snow-laden, were deserted, seemingly forgotten by the men and women who had spent so much time with them during the past months.

One ordinary day followed another. Every morning the water buffalo had to be groomed until they shone; the oxen had to be cleaned after the night in the dirty stall; these, as well as the sheep, had to be fed. Usually the animals received their meager rations before ten o’clock. Shortly thereafter the men, wearing their dirty-gray sheepskin coats, their brimless lambskin hats, and their pigskin sandals, congregated at the taverns to relieve the monotony of their daily routine. At noon they plodded home to a lunch of beans, looked after the cattle once more, and gave commands to their womenfolk. The rest of the day was spent at the taverns in drinking and talking, interspersed with long, easy silences. After the evening meal, the cattle were fed again. Then the men dropped off to sleep along with the rest of the household.

The winds and enforced idleness of winter were not alone responsible for the apparent sluggishness on every hand. Slow motion was characteristic of Dragalevtsy life in general, but especially of the bodily movements of the people. Ima vreme (there’s plenty of time) was either a practical philosophical tenet which explained their lack of hurry or else it was an expression frequently used to rationalize their casual manner. I never saw a peasant with a watch.

These quiet people of Dragalevtsy, whose way of life is not very different from that of peasants throughout the Balkans, are more than just Bulgarian peasants who arose in the seventh century from a dash of Tartar added to a predominantly Slavic mixture. They are a special breed of Bulgarians called Shopi, a term originally meaning boorish. That is, a Shop was a bumpkin. Some authorities say that this term was derived from sop, the long staff which the men of this area carried. Since those living in the Shopsko area, or the immediate vicinity of Sofia and Mount Vitosha, are in general more conservative than villagers elsewhere in Bulgaria, the word Shopi also carried the idea of backwardness and mental simplicity. Among the many attempts to explain the special physical characteristics of these people, the most plausible theory is that of descent from the Pechenegi, or Mongolian tribesmen who infiltrated into that section of Bulgaria and nearby eastern Serbia in the eleventh century. Historians deal none too kindly with these Pechenegi; nor do the Shopi receive many compliments in contemporary accounts. Even their physical appearance is considered unattractive by many other Bulgarians.

From faces naturally swarthy, further darkened and weather-beaten by sun, rain, and biting winds, the small round eyes of Asia stare through one without giving an inkling of the impression registered. In the thin-lipped mouths of the young the teeth are gleaming white; beneath the drooping mustaches of middle-aged men teeth show yellowish in a rare childlike smile; and toothless gums accompany the gray stubbly beards of the old. Straight, prominent noses lend ruggedness rather than beauty; the customary clipping of the scraggly black hair of the men reveals wrinkled, leathery necks; the hair of the women is worn in braids down the back, and hangs from beneath a kerchief that covers the top of the head. Here, too, age is clearly marked. The glossy, thick braids of the girls all too soon become, with advancing years, dull and thin and are often pieced out with other, brighter hair. The men are of medium height. Because their shoulders are so broad and their chests so powerful, their short, sturdy legs seem out of proportion. The women, slightly shorter, walk erect unless stooped by age. Hands seldom gloved in winter are rough and dirty and calloused. I often thought that one of the strangest things about death was the way it quieted the hands of these simple folk, who, although reserved in demeanor, constantly gestured when they spoke.

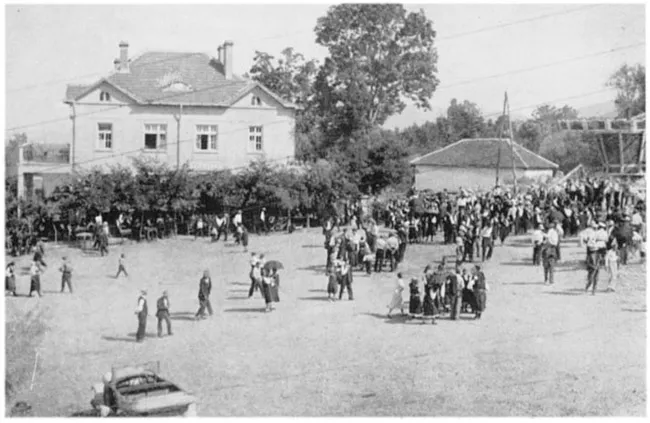

I grew accustomed to the mannerisms of the people as well as to the flavor of village life by slow degrees. At first I was attracted most by the gala occasions, or the spectacular. There was the annual Christmas horo (folk dance) which provided the first break in the monotony of winter. On a comfortably mild Christmas Day old women and little children, the first to arrive in the main village square, sat in twos and threes waiting for the dancing to begin. Girls in their Sunday best, with necklaces of gold coins flashing in the sunlight, passed through the square and sang as they walked. They were bareheaded, since they could not yet wear the married women’s head kerchief. As they drew closer, the blotches of rouge, the tremendous earrings, belts laden with clinking silver pieces, and heavy bracelets showed that the girls considered this no ordinary holiday. They formed a line, side by side, and began the dance after persuading the gypsy musicians to strike up a tune; one by one the boys who had come out of the taverns joined the moving line: one step to the right, one step to the left, then three steps to the right, kicking high as they stepped. As the dancing progressed, many married women participated, while the married men looked on with condescending interest. The little children, dressed like miniature adults, gathered on the fringes of the crowd to imitate the dancers. Gossiping groups formed, buzzed, and then dissolved to form anew.

A commotion arose in the center of the square as two young men fought over the cane which was carried by the leader of the horo. The leader was supposed to pay the musicians for the dances he led, in exchange for which he could direct the dancers in a serpentine movement, always in step with the music, so that they wound in and out with a “crack-the-whip” at every major bend of the line. To the peasant, the boisterous physical activity gives an exhilaration little else can induce. In fact, some of the “young blades” at this horo were so carried away with animal spirits that they performed six or seven steps to the prescribed two or three, tiring themselves out to the plaudits of those close by.

To the old-timers, however, the modern version of the traditional dance was a sad commentary on the state of things. They thought the young people too soft. After I had been watching the horo for some time an old man hobbled up to me. I had seen him shaking his head and muttering to himself, so I asked him, “What do you think of it, dedo?” He grunted, “It’s all right for the young people to have a little fun, but they aren’t as strong as I used to be when I was young. I used to hoe corn, harvest wheat, and come back to dance all evening. The young people can’t do that now. And I wasn’t as healthy as my father used to be.”

The village registrar, Bai Angel, told me why there had been a declining interest in the hora, especially those which used to occur around the neighborhood fountains. About seven o’clock the people used to go to the pasture to get their animals. If the animals were slow in coming, then the people danced the horo there in the fields. When the animals had been taken home, and after the girls had finished up their housework, they went with jugs to one of the three fountains in the village and there danced again until eleven o’clock. In 1924 more fountains were installed in the village, thus tending to break up the larger groups which gathered around the three original fountains. The girls preferred to carry water from the fountains nearest their homes, and no longer attended the evening horo.

Tavern life was another, less colorful way of passing the bleak winter days. In the four ill-ventilated kruchmi the men gathered to discuss the harvest and to argue over the news read aloud from yesterday’s newspaper. Some man sought his godfather, or the godfather of a recently christened son or daughter, and invited him to have a drink of rakiya (plum brandy) or wine. Sometimes men who had completed a business deal drank to clinch it. Men who had been in the army together told the same tall tales of adventure over and over again, re-creating those experiences which lifted them for a while out of their limited village environment. There were seldom any fights, because the frequenters put an end to disagreements before they got out of hand. The fact that not all patrons of the tavern drank liquor was shown by the comment of one of the villagers:

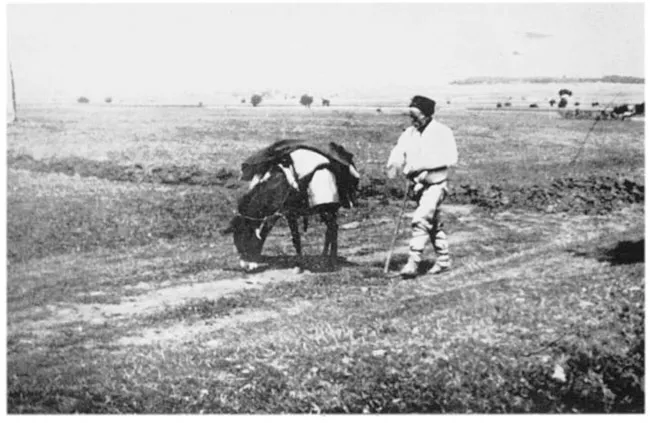

“Their round completed . . . the milkmen began . . . to retrace the long uphill journey from the city’s outskirts to the village.” See page 5.

“. . . in front of Bai Penko’s tavern on the northern side of Renaissance Square.” See page 8.

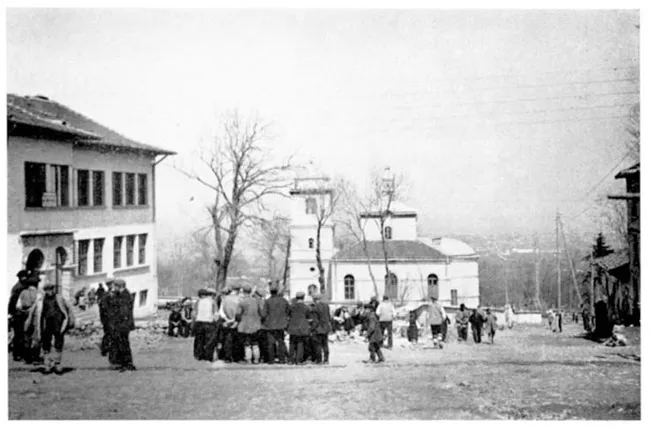

“The priest could look past the modern school building . . . to the church just beyond.” Sofia is in the background. See page 8.

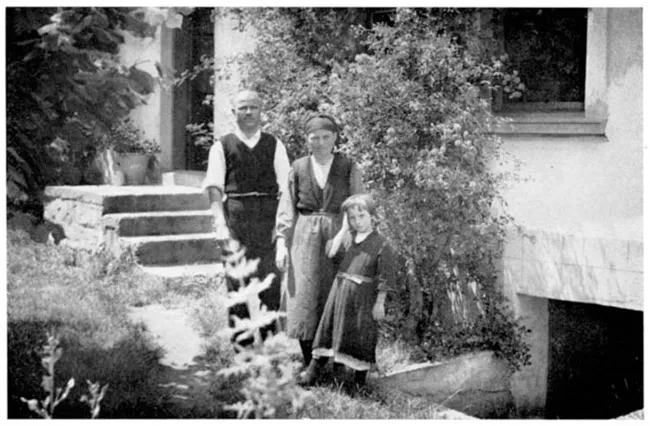

“Yurdan, the leading tailor . . . and his wife Zdravka were a unique couple.” See page 14.

“I come to the tavern chiefly for the newspaper. I have a strong will, drink little, and know when to stop. The young men when starting the temperance association asked me to be president but I couldn’t give up coming here for the newspaper. The small coffee house across the square has only room enough for five or six people and there’s no point in going there. Many blame me for going to the tavern, but they have no interest in finding out what is going on in the world.”

One advantage of visiting the tavern included the announcements that the town crier always made there as well as out in the square.

The tavern keepers, however, had no illusions about their standing in the public estimation. All of them were of the same peasant stock as their patrons, but had sold some of their land in order to set themselves up in business.

“If the people of the village took a vote, the majority would favor shutting up all the taverns. The people don’t like us,” was the tart comment of one tavern keeper. This dislike sprang from the indebtedness of so many people to the tavern keepers, as well as from the strong feeling many have toward the social consequences of excessive alcoholism.

There were, however, a number of men who had to miss the morning session at the Dragalevtsy kruchmi. They were the milkmen. Each morning while it was still dark eight tiny donkeys left their yards, pattered down the slope just outside the village, and followed the straight gravel road five miles to Sofia. They were accompanied by their prodding masters who kept an eye on the two or three large cans of milk which had been strapped onto the wooden saddles. These donkeys long ago learned to swallow any pride they might have had, for each morning, with monotonous regularity, they were overtaken by the high two-wheeled horse-drawn milk carts used by the remaining thirty Dragalevtsy milkmen. Once in Sofia, the majority of the milkmen covered their routes, knocking at the doors of the regular customers and waiting patiently for a container into which to pour a quart or so of milk from the large cans. The round completed, most of the milkmen began at once to retrace the long uphill journey from the city’s outskirts to the village.

Sometimes I overtook these men outside the village and fell in with them. “Dobra stiga” (“Well-reached”), I said; and they answered, “Dal ti bog dobro” (“God has given you good”). The amenities observed, I then asked about other matters. “How far is it from Sofia to your village?” Always the answer came in terms of “walking hours” and never in kilometers, the accepted measure of distance in Bulgaria. When we would encounter those going in the opposite direction we stopped our conversation long enough to say, “Dobra sreshta” (“Well-met”). When I chanced to inquire about the size of Dragalevtsy, the usual answer was, “About three hundred houses.” If I wanted to know how many inhabitants this would mean, I multiplied the figure by five, the size of the average household. (The difference between this crude estimate of fifteen hundred and the 1934 census figures of 1,669 persons meant little to the peasant.)

No, Dragalevtsy was in no sense of the word a large village, as Sofia savants used to point out to me when they asked where I saw material enough there for a book. Theirs was the loss. An old village with more than sixteen hundred people teems with life. The stuff of which its days are made is rich and lasting; the intricate crisscross of vigorous personalities and deep-rooted folkways proved a never-ending drama for which nature usually provided a superb setting.

The meadows were lush from the spring rains, some of the fruit trees were in bloom, numberless tiny silver streams spread a glittering net down the side of Vitosha, and a veil of green leaves lay over all the red roofs of the village. Against such a background, a group of peasants made ready for their pilgrimage to Rila Monastery. Such an occasion was as truly an outpouring of joy as was the departure of the Canterbury pilgrims in Chaucer’s day. The clanging of the church bell summoned the friends and relatives of the departing pilgrims to the incense-filled church. Inside, before the iconostas, dark and gilt, the priest read a prayer and led the little flock of people to the edge of the village, to the beginning of the outside world, where the travelers, dressed in their brightest, newest garments, were speeded on their way. The friends and relatives loaded them with money and presents of clothing, food, and wool, which the pilgrims were to donate to the great and holy monastery. The whole ceremony of leave-taking was made a part of the bright landscape by the flowers everywhere—on the dress of the pilgrims, fastened to the gifts, and carried in huge bunches. Upon their return a few days later the dusty pilgrims were met at the outskirts of the village and escorted home through the blue twilight by those eager to hear of every adventure during the days and nights in the great mountains, whose jagged walls have protected Rila Monastery for hundreds of years.

Formal piety, as shown in pilgrimages, was only one of the major characteristics which these Bulgarian villagers possessed. The Dragalevtsy people, especially the men, were predominantly literate. Bulgaria, despite what seems a forbidding Cyrillic alphabet, has the highest rate of literacy of all Balkan countries, a fact which can be attributed to the tendency to regard education as a panacea for individual and social ills. While only 44 per cent of the women over fifteen years of age could read and write, 92 per cent of the men were literate. Of course, I often came upon groups of peasants crowded around a friend slowly spelling out a newsp...