- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

At present, the Sibe language is the only still-active oral variety of Manchu, the language of the indigenous tribe of Manchuria. With some 20,000 to 30,000 speakers it is also the most widely spoken of the Tungusic languages, which are found in both Manchuria and eastern Siberia. The Sibe people, who live at the northwestern border of the present-day Sinkiang Uyghur Autonomous province of China, are descendants of the garrison men of the Manchu army from the eighteenth century. After annexing the area, the Manchus sent the Sibe's predecessors there with the task of guarding the newly established border between the Manchu Empire and Russia. They remained isolated from the indigenous Turkic and Mongolian peoples, which resulted in the preservation of the language. In the 1990s, when the oral varieties of Manchu became either extinct or on the verge of extinction, Sibe survived as a language spoken by all generations of Sibe people in the Chapchal Sibe autonomous county, and by the middle and older generations in virtually all other Sibe settlements of Xinjiang. Spoken Sibe is a carefully researched study of this historically and linguistically important language.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Spoken Sibe by Veronika Zikmundová in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

CHARACTERISTICS OF SPOKEN SIBE

This chapter contains more general information, which is important for the understanding of the detailed explanations that follow. It concerns phonetics, phonology, the lexicon and the definition of the parts of speech.

1.1 Notes on the phonetics and phonology

1.1.1 Problems of the phonological description of Sibe

The phonetic and phonological structure of spoken Sibe has been the subject of relatively little research. The greatest obstacle to clarifying the Sibe phonemic system in a way that would encompass the overall present situation is the great variance among groups of speakers and the fluidity in the pronunciation of the spoken language. The problems concern above all the distribution of allophones, which significantly differs in dependence on the age of the speakers, and, to some extent, on their adherence to one or another dialectal group.

The local variants of Tarbagatai, Nilqa, Gongliu and Ice Gašan are marked mostly on the levels of prosody, syntax and vocabulary. They concern mostly the older generation, because among the middle-aged and young speakers the knowledge of the Sibe language is considerably less frequent than in Chabchal.

Concerning the age of the speakers, the situation is more complicated and applies more to phonetics. Despite the fact that the language is currently undergoing changes and despite the variability of the mentioned idiolects, it is possible to define roughly two major varieties of spoken Sibe, which are considered to be correct by the speakers while differing from each other. Their origin is closely connected with the the cessation of the use of the Manchu script. Knowledge of written Manchu prevails among speakers born roughly before 1955.1 Among younger speakers, who grew up during the time when teaching and using Manchu script was forbidden, the number of those who can use it for recording of their own language is around a hundred people. (Kicengge, personal communication 2012)

The overall impression given by the present situation is that the spread of literacy constrained the natural tendencies in the development of the language, and the later loss of literacy among the bulk of the people accelerated phonetic changes, which then took place within one single generation. It is therefore possible to speak about the language of the ‘older generation’, which would include speakers born before 1955, and that of the ‘younger generation’, which would comprise speakers born approximately between 1955 and 19752.

Generally it is possible to say that in the speech of the older generation forms that are phonetically closer to the written language occur together with purely oral forms,3 while the younger generation employs only the oral forms. An illustration may be given by the expression meaning ‘ended, finished’: its written form is wajiha, with the equivalent oral form vašq, in addition to which the forms vajĭχ, vačχ, vačqa, vačq (and possibly more) may occur among speakers of the older generation.

It often happens that a word has either fallen out of use or has never been used as ‘colloquial’ by a certain group of speakers and is known to them only in the written form, while another group of speakers uses its oral variant. One example is provided by the general expression for ‘fruits’, Lit. Ma. tubihe, which was presented to me as a literary word for what is commonly known as suɹʁo jaq, lit. ‘apple thing’, by my Chabchal informants; only recently, however, I heard, in oral expression, the word tüvɣø from a 60-year-old speaker whose mother came from Tarbagatai.

1.1.2 Previous research of the Sibe phonemic system

The phonemic system of genuine4 spoken Sibe has been described several times. Probably the earliest description comes from Yamamoto Kengo as a part of his famous dictionary (Yamamoto 1969), followed by separate chapters in the two basic works on Sibe grammar: the classic of spoken Sibe studies by Jerry Norman (Norman 1974, pp. 163–164) and the description of spoken Sibe by Li Shulan et al. (Li Shulan 1984). Further there is a important article by Guo Meilan and Wang Xiaohong. Various details and aspects of the phonology of spoken Sibe have been discussed by native and Chinese scholars during the last 20 years. The most detailed description of the phonetic and phonological system of both spoken and written language (including a synchronic and diachronic comparative analysis) has been presented by Jang Taeho in his recently published book (Jang 2008, pp. 6–95).

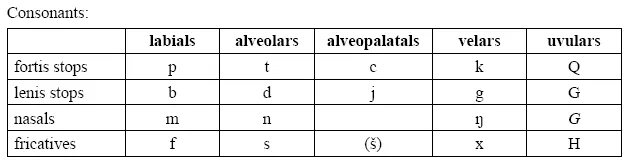

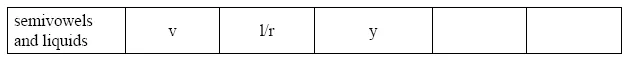

J. Norman describes the Sibe phonemic system as follows:

The description of the phonemic system by Li Shulan (pp. 5–7) generally resembles that of J. Norman but lists more consonantal sounds among phonemes than the latter.

The differences concern mostly back and front variants of sibilant affricates and fricatives (Norman: c [middle č] – Li Shulan: ch [back č] vs. q [front č]. These differences seem to be conditioned by the fact that, while J. Norman’s informants were an emigrant Sibe family who had left China in the 1940s, Li Shulan is a Chinese linguist, and her informants were most probably bilingual in Mandarin Chinese in which front and back sibilants are separate phonemes.

The detailed study by Guo Meilan and Wang Xiaohong agrees in most parts with that of J. Norman, except for the two varieties of sibilants, accepted by them as phonemically distinct.

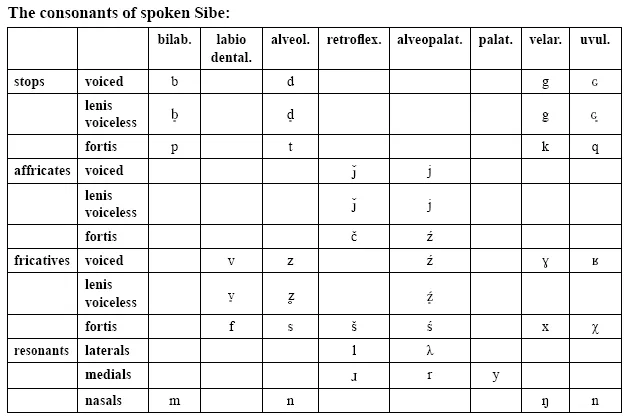

Wang Xiaohong and Guo Meilan present the following table of the Sibe consonantal phonemes:

To give an example of the present linguistic situation, in the speech of the oldest speakers5 there is no phonemic opposition between back and front sibilant affricates and the back and front variants are allophones conditioned by the following vowel, whereas the middle and younger generation perceives the two variants as separate phonemes and considers that there is a phonemic distinction between them.

In general, any investigation into the Sibe phonology is complicated by the fact that part of the speakers recognize written Sibe or written Manchu as the written standard of their speech, while the other part does not. For the first group it is natural to perceive the oral forms of words as realizations of their written forms, while the phonemic structure of the language of the second part relies only on the oral forms.6

1.1.3 List of sounds in spoken Sibe

In view of the precarious linguistic situation I do not attempt a phonological description of my own, and instead I list the sounds used in spoken Sibe and comment on their usage.

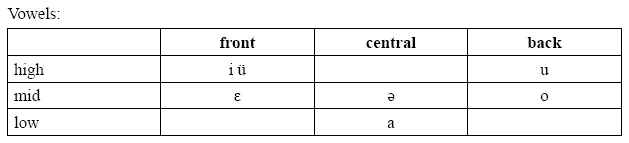

The vowels a, ε, ə, e, o, ø, u, ü, ů, i and ï occur in stressed syllables, and the vowels o, u, ů, ə, i and ï occur in unstressed syllables.

Palatal vowels

The palatal vowels are not noted in written Manchu. In Sibe they mostly occur in the vicinity of an i. The palatal vowels often merge with diphthongs: Lit. Ma. amargi, Si. εmirgi/εimirgi ‘northern’; Lit. Ma. dobi, Si. døf/düəf ‘fox’; Lit. Ma. turi, Si. türi).

Sometimes the palatal vowels occur in words without an i as in the cases of an elided k before consonants (Lit. Ma. sakda, Si. sait/sεt/set ‘old’). In some cases the palatalisation results in a change of the vowel quality (Lit. Ma. fonji-, Si. fienji- ‘to ask’).

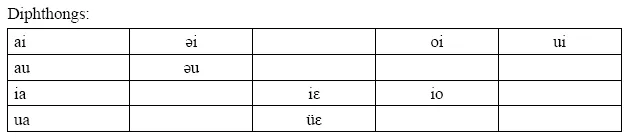

Diphthongs

The diphthongs which are probably indigenous to spoken Sibe are the closing diphthongs ai, oi, ůi, ei and opening diphthongs ia, io, iu, ie, u a, ao. In loan-words the diphthong ui is common.

The diphthong ue (written as uwe) of literary Manchu does not exist in spoken Sibe (Lit. Ma. kuwesi, Si. kuźi ‘knife’) and a secondary diphthong ao has developed by the elision of k before consonants (Lit. Ma. akdun, Si. aodun ‘firm, secure’; Lit. Ma. akjan, Si. aojun ‘lightening’).

Further, the opening diphthongs in Sibe often correspond to the closing diphthongs of literary Manchu (Lit. Ma. gayi-, Si. gia- ‘to take’; Lit. Ma. bayi-, Si. bia- ‘to ask, to look for’; Lit. Ma. boihon, Si. bioʁůn ‘dust, earth’).

In some cases there is a palatal diphthong in spoken Sibe corresponding to a simple vowel in written Manchu (Lit. Ma. foholon, Si. fioʁůlůn/føʁůlůn ‘short’).

On the whole, it seems that palatal diphthongs and palatal vowels in spoken Sibe are often interchangeable and their use varies individually.

The phonemes /g/, /k/, /x/ and /ŋ/ have velar and uvular allophones, which are distributed according to the place of articulation (uvulars in the vicinity of back vowels and velars in the vicinity of front vowels) the velar fricative [ɣ] and the uvular fricative [ʁ] are allophones of either the phoneme /g/or the phoneme /x/ in an intervocalic position.

The voiced consonants [v], [z], [ź] are allophones of /f/, /b/, /s/ and /š/ occurring both between vowels and in the initial position.

The sounds [j] and [ǰ] may be either the realization of the phonemes /j/ and /ǰ/, or allophones of /ć/ and /č/ in intervocalic positions.

Below I append several comments on the most characteristic features and developments in spoken Sibe.

1) Vowel harmony

Vowel harmony, which is present to some degree in most Uralic-Altaic languages, as well as in others and which is strictly observed in written Manchu, is relatively less consistent in spoken Sibe, especially in the younger generation. Still it is possible to state that vowel harmony is an effective principle of the spoken language.

The articulatory positions are, as in Mongolian, two – back and front. The back vowels are /a/ and /o/, the front row is represented only by /ə/, while /i/ and /u/ are treated as neutral. In fact, /u/ has two allophones – back and front – and it seems that in most words containing /a/ or /o/, especially in those with uvulars, the back allophone [ů] is pronounced. Exception are words with an initial /u/, which is mostly pronounced as [u] in words without uvulars. This, however, requires a detailed phonetic examination to clarify the precise phonetic qualities of the sounds.

The vowel /i/ generally retains its front vowel qualities, although a slightly lower and backer allophone occurs in the vicinity of uvulars.7 /i/, in its turn, has a strong palatalizing effect on the sounds in its vicinity.

2) Reduction of vowels

One of the most intensive changes that is currently taking place in the spoken language is the strong reduction of vowels in unstressed positions, which in some cases results in their ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of abbreviations

- 0 - Introduction

- 1 - Characteristics of spoken Sibe

- 2 - The Noun

- 3 - Qualitative nouns

- 4 - Pronouns

- 5 - Numerals

- 6 - Spatials

- 7 - The verb

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix

- Vocabulary

- References

- Summary