eBook - ePub

Self and Society

Are Communal Solidarity and Individual Freedom Allies or Antagonists?

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

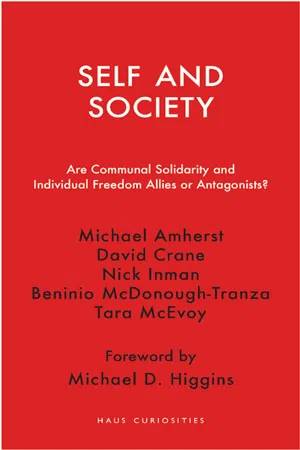

Self and Society

Are Communal Solidarity and Individual Freedom Allies or Antagonists?

About this book

A collection of five essays from the 2020 Hubert Butler Essay Prize that examine contemporary society, featuring a foreword from Irish President Michael D. Higgins.

Bringing together the winning and shortlisted essays from the 2020 Hubert Butler Essay Prize, Self and Society presents five fresh perspectives on the tension between individual freedom and communal solidarity, asking what we owe our communities and why it matters. With a foreword by Ireland's President Michael D. Higgins, the book examines themes that are more pressing than ever in the age of Coronavirus and Brexit, invoking the spirit of the Irish essayist Hubert Butler to investigate whether collective and personal aims can be synergistic or are destined to remain ever in conflict.

Winner Michael Amherst takes on identity politics, questioning whether the stratification of society in the name of social justice is helpful or harmful in the pursuit of equality. Runners-up Tara McEvoy and David Crane tackle, respectively, the necessity of collective action as a response to the current pandemic and other social crises, and the role of conflicts of individual freedom in facilitating or stifling the economic liberation of refugees. Special mentions have been awarded to Nick Inman and Beninio McDonough-Tranza for their respective essays on personal responsibility and the legacy of the Polish union Solidarnosc.

Bringing together the winning and shortlisted essays from the 2020 Hubert Butler Essay Prize, Self and Society presents five fresh perspectives on the tension between individual freedom and communal solidarity, asking what we owe our communities and why it matters. With a foreword by Ireland's President Michael D. Higgins, the book examines themes that are more pressing than ever in the age of Coronavirus and Brexit, invoking the spirit of the Irish essayist Hubert Butler to investigate whether collective and personal aims can be synergistic or are destined to remain ever in conflict.

Winner Michael Amherst takes on identity politics, questioning whether the stratification of society in the name of social justice is helpful or harmful in the pursuit of equality. Runners-up Tara McEvoy and David Crane tackle, respectively, the necessity of collective action as a response to the current pandemic and other social crises, and the role of conflicts of individual freedom in facilitating or stifling the economic liberation of refugees. Special mentions have been awarded to Nick Inman and Beninio McDonough-Tranza for their respective essays on personal responsibility and the legacy of the Polish union Solidarnosc.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Self and Society by Michael Amherst,David Crane,Nick Inman,Beninio McDonough-Tranza,Tara McEvoy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & European Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Tara McEvoy

On 14 July 2020, Conservative MP Desmond Swayne stood in the House of Commons and delivered a tirade against new plans to make face masks mandatory in some public places, an incentive to slow the spread of Covid-19, to ‘flatten the curve’ of the virus’s infection rate. ‘Nothing,’ he emphasised, ‘would make me less likely to go shopping than the thought of having to mask up.’ The requirement to do so, he argued, would be a ‘monstrous imposition against me and a number of outraged and reluctant constituents.’ Swayne’s protestations were out of line with majority public opinion in the UK at that time: 91 per cent of Britons thought wearing masks should be compulsory on public transport; 80 per cent thought the same for shops; 68 per cent thought masks should be mandatory in busy outdoor areas. But the MP wasn’t alone in his criticism of ‘having to mask up’. Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage, typically facetious, told Politico that the demand for members of the public to wear masks made him want to ‘stick two fingers up and shout abusive language at the television.’ At the end of the month, in the North of Ireland, Democratic Unionist Party MP Sammy Wilson tweeted a photo of himself in an ice cream parlour, unmasked and smiling, bearing the caption ‘Support local business. You can’t eat [ice cream] when you’re muzzled!’ And this was just what was happening in the UK. From country to country, different versions of the same debate were playing out. In Germany, individual states were given the power to impose their own rules on mask-wearing; in France, every shop owner could decide for themselves whether to make mask-wearing mandatory on their premises. Since it had started appearing everywhere from the supermarket to the train station, the face mask had rapidly become a symbol of ideology, a symbol of a perceived tension between individual liberties and the necessity of collective action.

In this respect, the face mask has epitomised something of the broader debate surrounding the response of individual countries to the coronavirus pandemic. How much personal freedom would each citizen be willing to relinquish, temporarily, in the interests of the public good? What sacrifices were too great? What could people bear, and for how long? The day after Swayne made his remarks in the Commons, I was making dinner and, in the background, put on an episode of Novara Media’s current affairs YouTube show Tysky-Sour, my laptop perched on a box of Cheerios laid flat on the kitchen counter. The host, Michael Walker, was discussing the political refusal to wear masks with John McDonnell’s former advisor James Meadway and Dalia Gebrial, an LSE academic. Walker, speaking from the Novara studio, argued that the UK face mask debate verged on silly – that it was a distraction from the real issues of the day – but then Gebrial started speaking about how the stakes were actually very high indeed. I turned down the heat on the hob, let the tomato sauce I was making simmer, and turned to watch the screen as she put into words everything that was revealed by this refusal, in terms I have been thinking about since:

It reflects these very narrow and individualised ideas of freedom that have really governed the West in particular since the rise of neoliberalism … It kind of looks at individual behaviour as only relevant or only important insofar as individually borne consequences. It doesn’t consider how perhaps minor concessions, or behaviours that may be minor to one person, could have significant impacts on the collective freedom – the idea that we are not just individuals existing in our little silos but actually our behaviour impacts on the collective good. That’s one thing this pandemic has really challenged. You don’t just have to think about your likelihood of getting the virus, or the consequences for you if you’re exposed to the virus … but think about being a vector, potentially transmitting it.

A vector: a single individual touching a whole network. For Gebrial, the argument struck at a key tenet of modern-day Western politics: it displayed how individualism had been valorised (there being, in the infamous words of Margaret Thatcher, ‘no such thing as society’), how acting in the public good had been ‘portrayed as a weakness’. It has, and continues to be: we see it in everything from the popularity of Bear Grylls – one man battling against the vastness and violence of nature – to the election of Donald Trump and the increasing populism of the political sphere, as other ‘big personalities’, ‘television characters’, take aim at the very idea of collective governance. We see it in an incessant media focus on people over policies. Arguably, we might read individual exceptionalism as a motivation behind the Brexit vote, too, influenced as it was by the rhetoric of ‘going our own way’, ‘taking back control’.

The same isolationist rhetoric was peddled out once again in the summer of 2020 as the refugee crisis intensified – those desperate people on boats and dinghies unable to simply ‘pull themselves up by the bootstraps’ – and as Britain responded by appointing a ‘Clandestine Channel Threat Commander’ to make their sea journeys to UK shores ‘unviable’ – a stroke of astonishing cruelty. As we entered the first lockdown, the acceptability – the valorisation – of radical individualism as a worldview, as a basis for behaviour, had resulted in supermarket shelves lying bare, stripped of essential produce as individuals rushed to shore up individual supplies, as we all rushed to safeguard ‘our little silos’.

On the Novara YouTube discussion show, Gebrial spoke, too, about the groups who were more seriously affected by a widespread ambivalence towards mask-wearing: older people, disabled people, those with underlying conditions. And it is true, of course, that different groups have experienced this crisis differently. In addition to those aforementioned, we might add people of colour, who, in the UK, have been disproportionately likely to contract coronavirus; working-class people, including those for whom it was impossible to work from home during the strictest phases of lockdown; and, abroad, people in countries with poor or privatised healthcare systems. For all the rhetoric of everyone ‘being in this together’, these divisions continue to make themselves felt. To paraphrase Orwell, we are all equal, but some are more equal than others. As the pandemic progresses, I have been routinely reminded of Friedrich Engels’ book The Condition of the Working Class in England, this passage in particular:

When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another such that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live … its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual.

What does freedom mean in this context? When we now act without communal solidarity, who gets to be free? Who remains oppressed; whose oppression is deepened? These questions were largely ignored in the UK as the government first dallied over acting to stop the spread of coronavirus, and then scrambled to piece together an adequate response, all too little too late. As in many other countries, public messaging on the pandemic response here has deliberately lacked clarity. While it has been heartening to see mutual aid groups seek to fill the void left by the government’s inaction, it’s enraging that they should have had to do so in the first place. In Belfast, where I live, as in many other cities across the UK and Ireland, a rising number of coronavirus cases in early March was met with an outpouring of neighbourly sentiment – and a good deal of practical help amongst neighbours. On Facebook, groups formed where people posted offers to go grocery shopping for people in their area, or pick up medicine for those who couldn’t make it out of the house. Posters volunteering assistance appeared in windows. A local art gallery and framing shop closed down and, in their newly imposed free time, its owner and workers started a soup kitchen, delivering meals daily around the city. Here was communal solidarity being used to facilitate individual freedom: the more responsibly everyone in the community acted, the safer – the freer – the most vulnerable would be. When the number of cases fell by enough, those shielding would be able to go outside again; we would all be able to see our loved ones again.

A couple of months into the first lockdown, stuck in the house, I read an interview with a Belfast-based artist, Jennifer Mehigan, on the art website AQNB. In it, she speaks about mutual aid, models for community care, and the prevalence of these models in certain queer communities:

Even the act of just caring for each other in times of crisis is so familiar in parts of the queer community and it was kind of nuts to watch people bury themselves into surviving as this individual thing and not looking to see who needed something more than them, but I guess that is the fun side of capitalism as always.

That was the other side of the coin: the logic of capitalism – the way in which market interests function as absolute priorities in our society – had become starkly, grimly apparent in the past few months, perhaps more so than ever before during the course of my lifetime, with those market interests pitted directly against public health. The same calculation at every stage of the pandemic: lives versus profit margins, public opinion tipping the balance slightly, the balance tipped back again by a relentless media campaign. Boris Johnson and Michael Gove and Priti Patel grinning, pulling pints behind the bar at a Wetherspoons as the death toll creeps steadily upwards. Rishi Sunak encouraging everyone to have a meal in their local Wagamama franchise. Freshly applied stickers on every shop window: Welcome home! We’ve missed you! A strange kind of freedom, a cost unevenly divided.

*

As summer wore on, as the race for a vaccine sped along, I returned to the poetry of Louis MacNeice. I had written a Master’s dissertation on his work a few years ago; I spent the summer working long shifts at a sandwich bar in a town an hour away, getting the bus to Belfast, heading straight to the library to find critical texts on his collections. It had been a frantic season, but my fondness for his work hadn’t diminished – there’s something profoundly reassuring about his voice. He’s the friend you’d call before a job interview, or...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Acknowledgements

- Frontmatter

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- Michael Amherst

- Tara McEvoy

- David Crane

- Nick Inman

- Beninio McDonough-Tranza

- Acknowledgements

- The Hubert Butler Essay Prize

- Backmatter