![]()

Chapter 1

DIVERSITY IN DESIGN

Thirty years after the dawn of the civil rights era, architecture remains among the less successful professions in diversifying its ranks—trailing, for example, such formerly male-dominated fields as business, computer science, accounting, law, pharmacology and medicine.

—Ernest Boyer and Lee Mitgang

ERNEST BOYER AND LEE MITGANG, in their seminal work, Building Community, raised a deep concern about the practice and study of architecture: “We worry about … the paucity of women and minorities in both the professional and academic ranks.” They based their findings on extensive research with architectural practitioners, students, faculty, and administrators. In a follow-up piece in Architectural Record, Mitgang called for an end to “apartheid in architecture schools” and argued that “the race record of architecture education is a continuing disgrace, and if anything, things seem to be worsening.”

While over half the users of the built environment are female and large numbers are people of color, population figures in early 2000 revealed that only 16% of architects in the United States were women, 4% of architects were of Hispanic origin, and 2% were African American. But these figures simply reflect individuals’ self-reports. Some individuals may call themselves architects but may not really be licensed in the profession. Others may not yet have passed the licensing exam, making them ineligible to assume legal responsibility for the design of a building.

How have the numbers of women in architecture compared with those in other fields? The U.S. Census data includes all persons who list themselves as architects, regardless of whether or not they are professionally licensed to practice. According to the census, women comprised 4% of architects in 1970, 8% in 1980, and 15% in 1990. While these figures show some increase, the representation of women in architecture is by far the lowest among many arts professions, including photography, music performance, and music composition. In fact, the rate of women’s entry into the architecture profession closely parallels that of women in medicine.

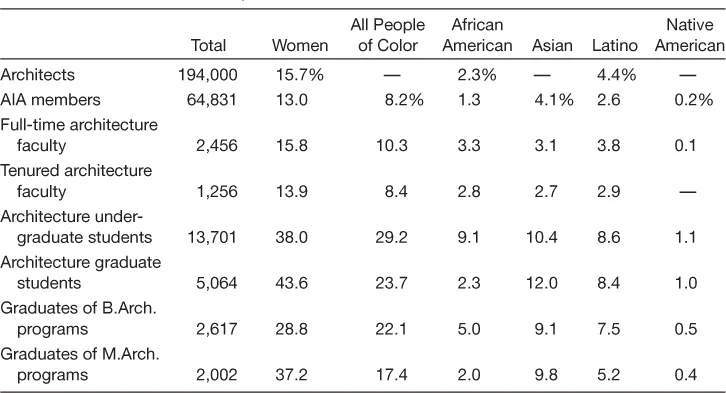

What about the representation of women and persons of color among architects who are licensed? Here the most reliable source is data from the American Institute of Architects (AIA), the major professional organization in the field. Table 2 illustrates the dramatic underrepresentation of women and persons of color in architecture across the board: especially in practice, as AIA members, and as full-time and tenured faculty. As of 1999, 13% of AIA members were women and only 8% were persons of color; of those licensed to practice (i.e., solely regular AIA members, excluding associate and emeritus members), only 10% were women and 8% were persons of color. No woman or person of color has yet received the highly coveted Pritzker Prize, the profession’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

Astonishingly few African-American architects are licensed to practice in some states. For example, in 1996, twenty-six U.S. states each had a total of five or fewer licensed African-American architects. Delaware, Mississippi, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Rhode Island each had only one. Idaho, Iowa, Maine, Montana, New Hampshire, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming had none. No wonder some critics have gone so far as to call African-American architects an “endangered species.”

TABLE 2. Women and People of Color in Architectural Education and Practice

Only 16% of full-time architectural faculty in American colleges and universities are women; just 10% are persons of color. For all tenured architectural faculty—those to whom their institutions have made virtually a permanent, lifetime commitment—the figures are even lower; only 14% are women and 8% are persons of color. About half the women (58%), Latinos or Latinas (50%), and Asian/Pacific Islanders (48%) and one-third the African Americans (34%) among architectural faculty are marginalized in part-time teaching positions, with little or no job security. In the early 1990s, similar statistics prompted an article entitled “Why Aren’t More Women Teaching Architecture?” in Architecture. In 1992, of the 108 architectural schools in the United States and Canada that grant tenure, 40 schools had no tenured women at all, and 27 had only one. As of the 1997–98 academic year, the 117 accredited architectural schools in the United States and Canada produced only 17 women administrators: 7 deans, 5 chairs, 3 heads, and 2 directors.

Of all undergraduates enrolled in accredited architecture programs in the United States at the close of the 1990s, 38% were women and 29% were people of color. Although these figures represent a substantial increase over earlier ones, the number of students far exceeds the number of those individuals who actually make it into the profession. In accredited graduate architecture programs, women comprise 44% and students of color make up 24%.

The number of African-American architecture students appears to be decreasing slightly, although until 1990 we had no way even to track this information. Prior to that date, the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) amassed data for “minority” students, but it did not subdivide it by racial or ethnic groups such as African Americans, Latinos/Latinas, Asian Americans, and Native Americans. As of the mid-1990s, African-American architecture students comprised only about 6% of the architectural student body. In 1995 only 32 African-American students across the United States received a master’s degree in architecture; by 1999 only 40 had done so. Furthermore, recent figures show a disturbing pattern of racial segregation in architectural education. Of the 1,313 African-American students enrolled in architecture schools in North America, 45% were students at the seven historically black schools with accredited architecture programs—Florida A&M, Hampton, Howard, Morgan State, Prairie View A&M, Southern, and Tuskegee—while the remainder were enrolled at the other 96 schools of architecture.

Such disturbing figures raise serious questions about the lack of diversity in the architectural profession today. Statistics like these perpetuate the image of the profession as a private white men’s club. To the outside world—and to many within the field—the profession seems incredibly insular and, compared to many other fields, archaic.

WHY DIVERSITY IN ARCHITECTURE?

Why do we need greater diversity among designers? And why is designing for diversity such a paramount concern? The built environment reflects our culture, and vice-versa. If our buildings, spaces, and places continue to be designed by a relatively homogeneous group of people, what message does that send about our culture?

Compared to most other countries, our American culture is a rich mosaic of racial and ethnic groups. With the latest waves of immigration, American cities are becoming increasingly racially and ethnically diverse, prompting a 1991 USA Today headline, “Minorities a Majority in Fifty-one Cities.” The accompanying article noted that during the 1980s, people of color tipped the population scales in seven cities with populations over 500,000, including New York, Houston, Dallas, San Jose, San Francisco, Memphis, and Cleveland. By 1990, Chicago’s Hispanics, primarily immigrants from Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, represented about 18% of the city’s population. African Americans were 37%. The Vietnamese have the fastest rate of increase of any ethnic group in Chicago, and Filipinos and Indians are close behind. Historically, the Windy City has had high populations of Italians, Greeks, Germans, Poles, and Irish.

These ethnic groups will eventually assume leadership roles. Several cities have already had African-American mayors and city council representatives: Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York, and Philadelphia. Yet the architectural profession in these and other cities is predominantly white.

ARCHITECTURE AS A CREATOR AND REFLECTION OF CULTURE

The lack of diversity in the architectural profession impedes progress not only in that field but also in American society at large. Throughout the world, architects create the places in which we live and work, from those where we are born to those where we die. The built environment is one of culture’s most lasting and influential legacies, a fact underscored by Sir Winston Churchill’s observation, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” Discrimination in the architectural profession can lead to discrimination in how we all use the built environment. In fact, it has done so for years.

Leslie Kanes Weisman’s book Discrimination by Design provides a thorough analysis of how the built environment has historically reflected and promoted the treatment of women as second-class citizens. Her work examines these issues in American housing, the office tower, the department store, the shopping mall, the maternity hospital, and elsewhere. As Weisman argues:

Public buildings that spatially segregate or exclude certain groups, or relegate them to spaces in which they are either invisible or visibly subordinate, are the direct result of a comprehensive system of social oppression, not the consequences of failed architecture or prejudiced architects. However, our collective failure to notice and acknowledge how buildings are designed and used to support the social purposes they are meant to serve—including the maintenance of social inequality—guarantees that we will never do anything to change discriminatory design. When such an awareness does exist, discrimination can be redressed.

Women, persons of color, certain ethnic groups, gays and lesbians, and persons with physical disabilities have historically been treated as second-class citizens in the built environment. In effect, their civil rights have been denied. For example, the Jim Crow laws that shaped the landscape of the American South from the late 1880s until the mid-1960s, forcing the construction of separate churches, schools, building entrances, restrooms, cemeteries, and water fountains for African Americans, reflected an oppressive, two-caste spatial system. So did the construction of Nazi concentration camps in Germany and Eastern Europe during the Holocaust, when over twelve million people—including six million Jews, Slavs, gypsies, gays, persons with physical disabilities, and other pariahs—met their deaths. In the United States, approximately 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry living along the West Coast, two-thirds of them American citizens, were forced out of their homes and into “relocation camps” during World War II. No doubt that these are the ultimate modern examples of discrimination by design.

Discrimination by design can be overt or covert. For example, in public places like theaters, stadiums, and airports, we see long lines of frustrated women waiting to use the rest rooms, while men are in and out in a flash. Architects and their clients, as well as building-code officials and others, never noticed that women take longer to use restrooms, and hence women’s restrooms need more toilet stalls than do men’s rooms. Had women been the architects, clients, and code officials, the built environment would likely be much more user-friendly to women.

Journalists have argued in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Working Woman, and publications across the country on behalf of gender equity in rest rooms. One of the more vivid accounts appeared in the New York Times Magazine:

I’ve seen a few frightening dramas on Broadway, but nothing on-stage is ever as scary as the scene outside the ladies’ room at intermission: that long line of women with clenched jaws and crossed arms, muttering ominously to one another as they glare across the lobby at the cavalier figures sauntering in and out of the men’s room. The ladies’ line looks like an audition for the extras in “Les Miserables”—these are the vengeful faces that nobles saw on their way to the guillotine—except that the danger is all too real. When I hear the low rumble of obscenities and phrases like “Nazi male architects” I know not to linger.

In the early 1990s, to accommodate the growing number of women senators, Senate majority leader George Mitchell announced that he was having a women’s room installed just outside the Senate chamber in the U.S. Capitol. At that time, only a men’s restroom was located there, marked by a sign “Senators Only,” an implicit assumption that all senators were men. Senators Nancy Kassebaum and Barbara Mikulski, who did not qualify for admission, had to trek downstairs and stand in line with the tourists. From the U.S. Capitol to fifty state capitols across the country, “potty parity” has often been a pressing issue for women legislators. One New York State assemblywoman reminisced: “We had to tell the doorman whenever we were leaving the floor to visit the rest room—it took so long to get there and back, we were afraid of missing a vote. … It was like getting a permission slip from your teacher.”

Some state legislators have required architects to design a greater or at least equal number of toilet stalls in women’s restrooms, compared to men’s, in newly constructed or remodeled public buildings. In 1987, California led the way. State Senator Art Torres introduced such legislation after his wife and daughter endured a long wait for the ladies’ room while attending a Tchaikovsky concert at the Hollywood Bowl. The bill became law that same year.

To a certain extent, residential kitchens are also sites of discrimination by design. Instead of standing up, wouldn’t it be more comfortable to sit down while washing a sink full of tomato sauce–stained pots and pans? Ironically, we have to be in a wheelchair in order to get architects to design a kitchen that we can use while seated. Many kitchens are designed with cabinets so high that women need step-stools to reach the shelves, placing them in danger of falling onto a hot stove or a hard floor. While American kitchens may feature the latest appliances and the most fashionable interior design, they often pose special problems for Asian-American women, Latinas, and members of other ethnic groups who tend to be shorter than the average white American male.

Even the projects of stellar designers highlight the need for greater sensitivity to the needs of women and other “diverse” users. Many of Frank Lloyd Wright’s housing design...