- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

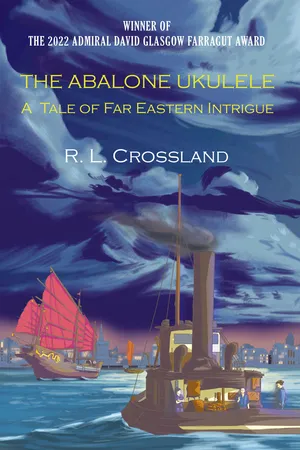

In this historical adventure, cultures from China, Korea, Japan, and the United States collide in 1913 over three tons of Japanese gold ingots.

Three ordinary men—a disgraced Korean tribute courier, a bookish naval officer, and a polyglot third-class quartermaster—must foil Japanese subversion and, with sub rosa assistance from Asiatic Station, highjack that gold to finance a Korean insurrection. Three ordinary women complicate, and complement, their efforts: an enigmatic changsan courtesan, a feisty Down East consular clerk, and a clever Chinese farm-girl.

It is a tale that wends through the outskirts of Peking to the Yukon River; from the San Francisco waterfront to a naval landing party isolated on a Woosung battlefield; from ships of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet moored on Battleship Row to a junk on the Yangtze; and from the Korean gold mines of Unsan to a coaling quay in Shanghai. Soon a foreign intelligence service, a revolutionary army, and two Chinese triads converge on a nation's ransom in gold . . .

Praise for The Abalone Ukulele

"A masterclass in historical fiction. With painstaking research and a gift for story spinning, Crossland brings to brilliant life a sprawling epic of greed, gold, and redemption. Crossland's gift for converting historic details into character and narrative makes The Abalone Ukulele an immersive read." —Joseph A. Williams, author of Seventeen Fathoms Deep and The Sunken Treasure

"Crossland's tale of shenanigans, greed, nobility, [and] slivers of grace propels across a geography spanning Shanghai, the Klondike gold fields, and San Francisco's wharves. His characters are elemental, with a commedia dell'arte quality . . . . Clues to a mystery are sprinkled skillfully throughout, keeping the reader turning the page." —Loretta Goldberg, author of the award-winning novel, The Reversible Mask

"Maritime historical fiction in the tradition of Patrick O'Brian." —Steve Robinson, author of No Guts, No Glory

Three ordinary men—a disgraced Korean tribute courier, a bookish naval officer, and a polyglot third-class quartermaster—must foil Japanese subversion and, with sub rosa assistance from Asiatic Station, highjack that gold to finance a Korean insurrection. Three ordinary women complicate, and complement, their efforts: an enigmatic changsan courtesan, a feisty Down East consular clerk, and a clever Chinese farm-girl.

It is a tale that wends through the outskirts of Peking to the Yukon River; from the San Francisco waterfront to a naval landing party isolated on a Woosung battlefield; from ships of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet moored on Battleship Row to a junk on the Yangtze; and from the Korean gold mines of Unsan to a coaling quay in Shanghai. Soon a foreign intelligence service, a revolutionary army, and two Chinese triads converge on a nation's ransom in gold . . .

Praise for The Abalone Ukulele

"A masterclass in historical fiction. With painstaking research and a gift for story spinning, Crossland brings to brilliant life a sprawling epic of greed, gold, and redemption. Crossland's gift for converting historic details into character and narrative makes The Abalone Ukulele an immersive read." —Joseph A. Williams, author of Seventeen Fathoms Deep and The Sunken Treasure

"Crossland's tale of shenanigans, greed, nobility, [and] slivers of grace propels across a geography spanning Shanghai, the Klondike gold fields, and San Francisco's wharves. His characters are elemental, with a commedia dell'arte quality . . . . Clues to a mystery are sprinkled skillfully throughout, keeping the reader turning the page." —Loretta Goldberg, author of the award-winning novel, The Reversible Mask

"Maritime historical fiction in the tradition of Patrick O'Brian." —Steve Robinson, author of No Guts, No Glory

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Abalone Ukulele by Roger Crossland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Crime & Mystery Literature. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

YI’S STORY

Seven times down, up eight

—Korean proverb

Map of 1911-13 China and Korea © R. L. Crossland 2020, Artwork by “RenflowerGrapx (Maria Gandolfo)”

CHAPTER ONE

Tientsin, China, 1893 – file Alpha, folder one

Sergeant Go scuttled across the bow of the junk Jilseong and found his officer, Korean Army Captain Jung-hee Yi, prone on the foredeck. He was scanning the waterfront with those ungainly, expensive night field glasses of his.

Yi said nothing and Go knew what that meant. He was searching each lantern-illuminated face on the pier for some hint of special attention.

No suggestions, no indications, no apparent threat.

“Everyone pictures emissaries as clad in silk, wearing ceremonial daggers. If they only knew how much time we expended these days ankle-deep in ox manure,” the heavy-shouldered captain confided.

Sergeant Go squatted next to him, looked thoughtfully at his own mucky feet, and chuckled. Then he stifled a cough. Taking the night glasses, he panned full circle, watching for that single aggressive movement from any unexpected quarter. The advantage to the outsized front lenses of the night glasses was they collected more light facilitating better defined images.

He caught the eye of each of the two courier detail lookouts and waited for them to acknowledge. He studied the junk’s captain who overlooked the helmsman and his five crewmen as they stood ready to handle lines.

“It’s diplomats they associate with manure, not couriers,” Go rasped with a snort of derision. “Not much we can do. Not feeding the oxen for two weeks before a jaunt just won’t work.

Several of Yi’s men were rigging the derrick that would lift the oxen out of Jilseong’s hold in belly slings. The derrick wasn’t large enough to swing them over the side safely. The Korean junk’s narrow beam required the oxen be first deposited on deck, and only then, moved to the pier. The tribute silver was equally heavy and would follow the same route.

Yi’s methodical planning had assured the junk made landfall and passed the Daku Forts by dusk. He always consulted the I Ching, the Confucian Classic of Changes, studiously thinking through the six variables to each successive operational challenge. And then addressing the six options each variable generated. It was his duty. His beliefs required he achieve his potential and honor the ancestors always.

They’d doused their sails and then surged up the Hai River to the piston rhythm of the auxiliary steam engine. A series of four pagodas marked a river more sinuous than a dragon’s back.

Now, the third pagoda loomed dead ahead marking the terminus of the boat segment of their journey. On either side of the river lay the dimly lit structures known as the “Long Storehouses.” It was 100 li from the Forts to the walled inner city of Tientsin. They were at the 85 li mark.

“I miss the old procession deliveries, all the rippling banners, the bells and gongs. They were festive affairs.” Sergeant Go mused. “On the other hand, those Porro prism glasses make it so a man can pluck the shadow off a silhouette.”

Annually Korea paid China tribute in silver, copper, ginseng, and other goods valued at about 30,000 tael. A tael was 1.2 ounces of silver frequently fashioned into boat-shaped ingots, sycee, of different denominations. When paid in silver exclusively, the total yearly silver shipment weighed eighteen tons.

Yi was ten years younger than Go. They and their men, were part of the organization that made those payment in several installments. Korea paid tribute and in return, China agreed to safeguard Korea and remain out of its internal affairs.

Yi nodded. He knew Sergeant Go played the simple soldier, but his contemplative sergeant knew there was nothing simple about courier duty — even in the procession days. Go was always analyzing the next step, the step after that, and projecting prioritized options.

Yi could make out the pier now. Behind it was a ramshackle warren of sheds, shacks, and godowns that spread left and then up the river. A floating hedge of junks rafted one and two-deep opened to receive Jilseong which trebled their size. The junks weren’t pickets, rather residential and bumboat squatters at sufferance. They maintained their unofficial night anchorages pointed upriver for a small fee as long as they kept confidences and didn’t interfere with important commerce. The junk-curtain flapped to one side, just enough to allow the Korean junk to tie up.

The oak double-timbered junk rode low in the water. He still feared grounding on a river shoal, even pier side.

The weight of Jilseong’s cargo was significant, when added to the weight of the English-built boiler and triple-expansion engine which were confined in steel-lined compartments. In a couple years, he planned to replace that engine with a British steam-turbine engine. The prime and secondary steering stations were inconspicuously sandbagged in a web of tarred line. The builders had fashioned an armored (and uncomfortably compressing) “crib” below deck to shelter the crew and courier detail. A similar crib craddled the silver.

The junk’s speed under steam guaranteed few ships could catch her, but her draft made grounding on a river shoal, an ever-present danger.

This was Tientsin, gateway to Peking, one of several unheralded points of delivery, an upriver port of the Hai River. The city’s borders encompassed the three foreign concessions of Britain, France and Japan, and the ancient walled inner city. Other foreigners, Russians, Germans, Austro-Hungarians, Italians, Belgians, Americans, and Koreans, walked its streets without attracting attention.

Within minutes they tied up the ramp, to Sergeant Go’s monosyllabic commands. Single syllables did not betray accents.

When Jilseong’s crew was done, Sergeant Go stomped on the deck three times and the remaining sixteen men of the courier detail filed on deck to offload cargo.

The night was cool, yet every man’s tunic was soaked in sweat. Several of the detail – their carbines wrapped in rolls of cloth like bedrolls — took positions behind crates and baskets. None wore uniforms.

“Ready to offload sacks of ‘iron ore’?” Yi asked.

Go bristled, though not because he was the elder. Yi realized he’d unconsciously struck a nerve. Officers attended to grand concepts, noncommissioned officers like Go, made things happen. They were always ready to address the practical.

Oxen, unlike horses, grew restive if they had to stand in one place for long. They needed to be loaded with the silver in the staging area ashore quickly and moved quickly. Loading the oxen’s massive arching packframes on a swaying deck risked capsizing the junk.

“Does the sun go down at sunset? Does snow ever blanket Mount Baektu’s peak?” Sergeant Go answered, raising one eyebrow. “You have a gift for these new ways, and more tricks than a shaman, still there are things you have to learn, and I, cousin, am here to suggest them. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. We’re both plowing new furrows in uneasy times.”

“I wouldn’t doubt there was a shaman somewhere in your bloodline,” Go added almost resentfully.

Yi knew the readiness question was wrong the moment he’d asked it, though he was anxious to move the evolution along. Who in his position wouldn’t be?

Sergeant Go, a distant relation, gave his stocky captain hints how to be a good officer when no one was looking. Sergeant Go was steady, reliable, and circumspect. Yi was mugwa, the military officer caste of Korean of the yangban aristocracy. He had passed the exams required to take his commission.

Go’s family had once been yangban, too, but three successive generations of his family had failed to pass the civil or military examinations. This failure relegated his family by law to the next lower class, the jungin. He had served with great merit to achieve his present position. He galled at the slightest suggestion of incompetency in his current role. Whatever Go’s issue, Yi knew it wasn’t with him personally.

Then too, Yi had overheard a discussion between Go and one of the men. Evidently Go was not happy with shamans, healers, or fortune-tellers this week.

Go was as lean and tough as whipcord, nevertheless Yi wondered if his health, or the health of some other member of his family, was failing. Yi was struck by the thought Go had seen a shaman recently.

Yi wanted to ask, to assure him that he was an excellent soldier.

He wanted to tell Go that three generations of scholarly failure meant nothing in the real world. Yet, Yi couldn’t cross the line, it would only make things worse. “Always the ancestors,” Yi sighed feeling obliged to reveal his personal demons and trying to end the exchange. “Oh, a mythical bear who became a woman and mother of the Korean nation is in the Yi bloodline surely. But no shamans we admit to. Can’t a man ever be alone and free of the ancestors? ”

Go having made his point, smiled avuncularly, and returned to the oxen.

Points of transition were particularly vulnerable to ambush, he knew, and needed to be addressed smartly. The time constraints on unloading added to the general tension.

After a rough crossing, Go imagined the oxen would be relieved to place their hooves on a stable surface. Below, they had been chained and bolted into position. Oxen were inclined to bunch up, and stampede, even in a confined space. Their combined weight, if they were allowed unrestrained movement, was capable of capsizing the junk. That was a risk, even tied to the pier.

Right away he saw a problem. The lead ox baulked at descending the ramp.

Sergeant Go strode quickly to the first ox and adjusted its blindfold downward. Oxen could only be led across a ramp like this one blindfolded.

The mess created by the bowel-vacating oxen below had coated feet and hooves with ordure. The first drover, a new man, had concentrated on his beast’s footing, not the position of its blindfold.

Yi caught Go’s attention and made a hand gesture signaling “well-done.” Let all our problems be so easily resolved, thought Yi, skimming his drover’s switch along the junk’s rail.

Moments later, his men were leading the remaining seven oxen from the heavy-timbered junk to a small staging area.

As the last blindfolded ox was led down the ramp, Yi was reminded that male oxen were invariably castrated. It made them steady and reliable. All their oxen were, in fact, males; male oxen were larger and could carry larger loads.

Debarkation had required concentration on the ramp. Now in the gloom, Yi could dog-trot to the eight oxen and pack-frames ashore and focus his efforts there.

“Strong and docile,” one of his men observed reading Yi’s mind. “Thankfully, we’ve been allowed to remain strong and decidedly un-docile.”

The lead drover, Corporal Mun, was organizing the staging area and gave Yi a crisp, almost imperceptible, nod of the head.

“Oxen at the back, ox packframes, left; ordnance sacks center; the two ‘ceramics’ jiges, right. Don’t even think of dropping those ‘ceramics,’ brothers. Keep them well clear of those heavy-hooved beasts back there” the corporal susurrated as each detail member deposited a portion of the cargo.

He looked directly at Yi, accompanying that last caution with a brief flare of his eyes.

Each ox packframe resembled the picturesque Camel Back Bridge in Peking. The pack-frames were designed to straddle an ox at its midsection. Beside the frames, sacks of iron ore tailings stacked in groups of five concealed the silver tael. Yi’s men, experienced drovers, quickly cinched on the arched pack-frames and loaded the sacks.

Ordnance included extra carbines and ammo, and curved, single-bladed swords, in straw-stuffed sacks.

These jiges were A-frame man-packs designed to carry an innovative item Yi had recently introduced to the detail’s organizational gear.

The ox-train floated soundlessly through the alleys and along the footpaths, hastening down a series of narrow alleys and footpaths that would have proved impassable by ox cart. The ox-train moved along the bank gradually angling northward. These oxen didn’t respond to voice commands. Instead they responded to a code of whacks on their haunches by way of a switch. The occasional lowing attracted no attention.

Oxen transport was a mode that traced both sides of the Yellow Sea with ubiquity. The courier detail set course to a prearranged livestock pen with sheds and a walled paddock on the outskirts of Tientsin.

They arrived at the paddock a few hours later. The stonewalled enclosure looked tired and its mortar had degenerated to light grit. Its first course had been built finger-tip-to-shoulder high using mortar and stone. Later, another course, the same height, had fortified the paddock with the same materials, plus timber posts and shoring.

Once there, the men bivouacked behind the shed, upwind of the aromatic manur...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- PART I - YI’S STORY

- PART II - THE LANDING PARTY

- PART III - THE BOARDING PARTY

- PART IV - THE LAGANING DETAIL

- PART V - DUNGAREE LIBERTY

- Historical Notes

- Glossary (read first)

- Naval Officer Ranks/Enlisted Grades

- Character List