- 310 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Leber's thumbnail portraits bring to life and record the heroism of sixty-four members of the Resistance from every walk of life. Their stories are sometimes spectacular, often quiet and almost commonplace accounts of men and women striving to maintain dignity and decency in the face of the ruthless, total power of the Nazis

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conscience In Revolt by Annedore Leber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

2

LEARNING

DOI: 10.4324/9780429039027-10

THE National Socialists were not content with political mastery. They demanded also that their doctrines and ideologies should be accepted by each and every individual and that the state should order the Weltanschauung—the whole attitude—of all the people; to this end they embarked on a ruthless course of suppression and annihilation.

Many of their methods are well-known: the police state, the censorship, the control of education and the propaganda machine. When Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda and a central Ministry of Education (education was normally the concern of each Land) were set up, the intention was all too clear. Among the earliest measures taken by the new government were the ‘cleansing’ of the universities and schools, the banning of dissident newspapers and periodicals, the suppression of writers whose opinions did not conform and the barbaric public burning of books. The inquisition of the mind reached a climax on 10 May 1933, ten weeks after the Reichstag fire and while the atmosphere of political terror still reigned, when huge bonfires raged in the Gendarmmarkt in Berlin and in many other public squares. Many famous books by living authors who had added to Germany’s fame as a literary and scientific nation, and practically all European literature since Voltaire which might possibly stimulate the German reader to reflect on the spirit of the new régime, belonged to the Schmutz-und-Schundliteratur which was sent up in flames by order of Goebbels.

Hundreds of writers and scientists had to leave the country of their birth. Many lost their lives. Others were frustrated by the ban on speech and publication, or driven to other and unaccustomed occupations; if, that is, they were spared the concentration camp, or death. Emigration, actual or spiritual, became the only alternative to subservience. The National Socialist state had in its hands all the weapons it needed to enforce compliance.

Anti-Semitism was one of them; it was in fact a corner stone of Nazi policy. Economic, social and racial prejudices were systematically fostered, built up into a philosophy of envy and hate. The amateurish racial theories of Hans F. K. Günther and Alfred Rosenberg purported to give to the despotism a pseudo-scientific basis and to provide in the primitive cult of the ‘master race’ an intellectual justification for its policy: the policy whose practical results were the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

The propaganda for the ‘master race’ theory was carried into the smallest villages; the notice ‘The Jews are our misfortune’ appeared everywhere in shop windows; Der Stürmer carried endless perverted scandal stories. The Nazis were at some pains to give a legal veneer to their annihilation campaign, and one inhuman law succeeded another. First came the dismissal of all Jewish officials, then their exclusion from all professions; followed by deprivation of citizenship, imposition of higher taxes, compulsory labour and finally discrimination in private as well as public life: they were branded with yellow stars, not allowed to have pets, cars, telephones or wireless; to buy books or newspapers, nor even to use automatic ticket machines or public telephones. On the notorious Kristallnacht, in November 1938, a mob; organised by the authorities, demolished their shops and burned down their Synagogues, without opposition from the police, in every German town.

Those people who retained their independence in face of such doctrines came up against the full power of the machine, and found that they too incurred, first, defamation, then persecution and finally death. But there were scientists, teachers, journalists and men of learning who stood up to the Nazi disciples of ‘Culture’ and ‘Race’ against the bogus racial theories, the abuse of medicine to allow euthanasia, forced sterilisation, experimental murders and finally against legal mockery and the national policy of war. They were ready to give up their lives in defence of the freedom of the mind, and by doing so they challenged the arrogant belief of the tyrants in power that the mind is something that can be bought, conditioned, degraded and enslaved.

CARL von OSSIETZKY

3 October 1889—3 May 1938

DOI: 10.4324/9780429039027-11

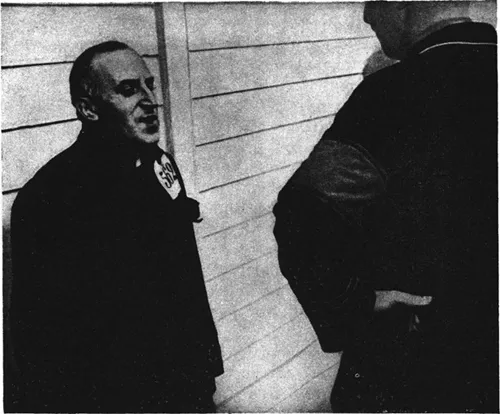

CARL VON OSSIETZKY came from a lower-middle class Catholic family in Hamburg. He won an international reputation as a journalist and died on 3 May 1938, as a prisoner of the Gestapo in Berlin.

He was one of the first victims to be arrested on the morning after the Reichstag fire, and his martyrdom in concentration camps lasted for more than three years. But when the Berlin Propaganda Ministry learned that he was being seriously considered in Oslo for the award of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Gestapo were obviously much embarrassed and ordered that he should be taken to a prison hospital in Berlin.

Four months later, a few days before the final decision of the Norwegian Nobel Prize Committee, Hermann Göring had the powerless ‘deadly enemy’ brought into his office, so that he could talk to him; and there, now with threats and now with flattery, he tried to extract from Ossietzky a promise to the effect that, should the Nobel Prize decision fall in his favour, he would reject it with some sort of personal declaration as to his unworthiness; if he would do this he would be allowed to go free and to enjoy material security, and be left in peace. Ossietzky said ‘No’, and went back to his prison.

A week after this discussion, while German newspapers and broadcasting stations were spreading the provoking news—and describing it as ‘an impudent challenge to the “Third Reich” ‘—the prize-winner had been moved, on Göring’s orders to a municipal hospital, where he lay under strict arrest and special supervision. In Oslo however, the President of the Nobel Prize Committee received the following telegram: ‘Grateful for the unexpected honour—Carl von Ossietzky.’ The sender had to pay for it by life-imprisonment, but no one had dared hold up his message. This courageous decision, in spite of all the pressure which was put upon him was in fact the measure of Ossietzky’s character, for such decisions determined the part he played in public life in Germany.

In his youth, in Hamburg, Ossietzky’s fight—a journalistic fight—was directed against the influence of the army in the home and foreign affairs of the Reich. When he was thirty he came back from the western front, where he had fought as a private soldier, deeply shaken and embittered by the war experiences of his generation, and brought back with him the firm resolve to devote his energy and talents to opposing all and any forces which might bring about another war; and to work no less energetically to build and to protect a free, democratic Republic, ruled by citizens who were glad and proud of their responsibilities.

Photo from Tagesspiegel files

Carl von Ossietzky in Papenburg-Esterwegen concentration camp, where he received the following information:

THE NOBEL COMMITTEE of the NORWEGIAN STORTHING has in accordance with the provisions laid down by

ALFRED NOBEL

in his Will of November 27 1895 awarded the

NOBEL PEACE PRIZE for 1935 to

CARL VON OSSIETZKY

Oslo, December 10, 1936.

To those ends, he first went to Berlin as Secretary of the German Peace Society, then became editor of liberal newspapers and periodicals and found, in 1927, as editor of the Weltbühne, a platform which satisfied his insistence on complete freedom of speech and which was well suited to an intellectual guerrilla who lacked only the sharp elbows of the successful politician.

Ossietzky wrote in a brilliant, versatile, aggressive and often bitingly witty style. As German politics degenerated into a latent civil war between the left-wing radicals and the right-wing and conservative groups, Ossietzky emerged as a bulwark against the National Socialist threat; and as a critic of the parties of the right which were friendly disposed towards Hitler and of the military and legal forces which were prepared to compromise with Nazism.

Ossietzky brought to light in his periodical the work of many pro-Soviet writers, but he himself complained that ‘the word “freedom” is given no place in the vocabulary of Red Russia’, and that Moscow wanted to pack the European affiliations of the Communist Party with their ‘weak-willed satellites and half-witted slaves’; meanwhile the men charged with the protection of the Republic and of freedom in Germany were clearly told where they had gone wrong, by commission or by default as the case might be: so it was not surprising that he had to meet attacks, as he himself put it, ‘from the Right, accusing me of betrayal of national interests, and from the Left, charging me with irresponsible carping aestheticism’.

The first great test came with the famous Leipzig trial before the Reich Court, which took place in secret in 1931. Ossietzky was sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment on a charge of ‘treason and betrayal of military secrets’; the result of violent attacks in the Weltbühne in which he had stated that camouflaged funds, withdrawn from parliamentary control, had been put at the disposal of certain military departments, and that they were being used on Soviet territory, with the co-operation of the Soviet government, for the secret but intensive production of air armaments for Germany. Ossietzky could easily have avoided his prison sentence by going abroad, for the guilt-ridden authorities would have been in no position to interfere. But he maintained that the Weltbühne could remain true to its reputation only if its editor identified himself with its policy and if, when things became difficult, he chose ‘not the convenient solution, but the necessary one’. Ossietzky remained in Germany and went to prison.

Seven months later, after he had been released under the Christmas Amnesty of the Chancellor, von Schleicher, he again refused, in February 1933, to choose a ‘convenient’solution. After Hitler had become Chancellor, his friends implored him to save himself in time by going abroad. ‘After my final election article,’ he replied. He did not want to leave until he had made this last attempt to avert evil. On the same night that Ossietzky’s last warning cry was printed, the Reichstag was set on fire, and at 5 o’clock in the morning they came to fetch him.

In the concentration camp, whenever Ossietzky bled from the blows of his tormentors or collapsed with a heart attack during hard labour, they would allow him a few days rest on his wooden bunk, and then a high Nazi official would appear and suggest that he should sign a release petition saying that he had ‘revised’ his opinions. To this compromise with dictatorship Ossietzky said ‘No’, and for his ‘No’ he was silenced by slow, murderous ‘special treatment’ until, ill beyond hope, his life quietly slipped away in the darkness of isolation.

FRITZ SOLMITZ

22 October 1893—19 September 1933

DOI: 10.4324/9780429039027-12

FRITZ SOLMITZ was born in Berlin, the only son of well-to-do parents. He studied national economy at Freiburg University for one term and in August 1914 volunteered for military service, but owing to an accident his call-up was postponed until 1915.

Fritz Solmitz’s experience of war on the western front mad...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Resistance and Conscience: An Introduction

- Introduction

- Preface

- Youth

- Learning

- Friendship

- The State and the Law

- Tradition

- Christianity

- Freedom and Order

- Bibliography