- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

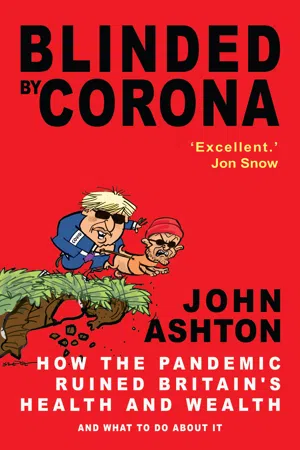

About this book

A gripping view of our fight against corona

Professor Ashton has deep practical understanding of the science of public health - a discipline invented in Britain - as a former Director of Public Health. In this jargon-free fly-on-the-wall tale he sets the UK government's measures to deal with COVID-19 from January against two centuries of home-grown knowledge. How do the government's experts and the UK's reliance on web-based solutions such as Test&Trace measure up against the past, for example the 2008 Swine 'Flu epidemic?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Blinded by Corona by John Ashton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Epidemiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Plagues in History

The idea of epidemics as ‘plagues’ has a provenance dating back to the book of Exodus in the Old Testament of the Bible. There the term was used generically to apply to catastrophic events, including a population being overwhelmed by frogs, lice, boils and locusts among the ten disasters inflicted on Egypt by the God of Israel to force the Pharaoh into allowing the Israelites to escape from slavery.

It was not until the sixth century, with the first recorded pandemic of infectious disease, that the term acquired a connotation that is understandable in terms of modern biological knowledge. That Justinian plague from 541-549 AD, caused by the bacterium Yersinia Pestis was carried by rat fleas and spread on board ships throughout the Mediterranean and Near East. With the centre of the epidemic in Constantinople, the disease affected the Roman Emperor, Justinian, who recovered from it, but it killed an estimated fifth of the capital’s population. However, probably the two best known outbreaks of the plague in the western world are the Black Death of the fourteenth century and the Great Plague of London of 1665-66, immortalised in Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year published in 1722.

The Black Death, or Bubonic Plague, also carried by infected fleas, is claimed to have been the most fatal pandemic in human history. Deaths are estimated at between 75-200 million worldwide including over one third of the European population, having arrived in Europe via the trade routes from Asia. The pattern of the clinical infection was unremitting, causing inflamed lymph glands or ‘buboes’ especially in the groin, swollen tongues, spitting headaches, severe vomiting and blackening of the skin, generally leading to an agonising death.

200 years later, when the Great Plague of London decimated the population, the epidemic spread from overcrowded parish to overcrowded parish in the rapidly growing city, with escalating death rates, especially among the poor. The wealthy fled to their country properties where they could, taking the infection with them to smaller towns and rural areas. The most notorious rural outbreak was in the village of Eyam, in Derbyshire, where 80% of the villagers died having stayed put and self- quarantined to avoid spreading the plague to other settlements.

In Defoe’s retrospective account there was speculation among Londoners that the causes of the plague went beyond the overcrowding of the slums to more mystical, religious and magical explanations as foretold by the appearance of comets and stars. Other aspects of Defoe’s observations that have resonance with recent experience with COVID-19 include efforts to certify people as free from disease to allow them to travel; measures put in place to achieve social distancing by pedestrians walking down the centre of highways to avoid affected households; the challenges of mass burial, and arguments about the validity of death statistics. Defoe noted that the numbers of ordinary burials in which plague was not mentioned as a cause of death, increased substantially during the period of the epidemic in those parishes most affected, drawing attention in effect to the greater validity of measuring all-cause mortality in assessing its impact.

However in terms of plague literature it is Albert Camus’ novel The Plague that provides the most enigmatic account. Set in Oran, a coastal town in Algeria, where the writer had lived, the novel explores many themes of an epidemic in a closed community in lockdown which have become familiar during the COVID emergency. These include vacillation over calling the epidemic, conflicts over quarantine and the lockdown itself, the vulnerability of the poor and disadvantaged, the pain of separation, complacency and hubris, the role of religious assembly in disease transmission, censorship of the press and news management, arguments over the science, the handling of mass funerals and rows about calling an end to the epidemic.

Although it is these well-known and devastating, large scale epidemics that have captured popular imagination, other infectious diseases have periodically demanded concerted action by governments and later by international agencies. Historically outbreaks have often been associated with population movements and mixing relating to trade, colonial exploitation, war, and travel for leisure, especially when travellers have introduced previously unexposed populations to new infectious agents.

Whilst it is true to say that in most wars disease accounts for more deaths than the actual fighting, it is especially the case that venereal infection is strongly associated with military mobilisation. Syphilis seems to have been brought back to Europe by Columbus’s 1492 expedition to the New World leading to an outbreak in the French army during the battle of Naples of 1495 and was second only to the Spanish ’flu as a cause of sickness absence among American troops in World War I. Such were the levels of venereal infection among British troops returning from the trenches in 1919 that a network of special clinics was established by local authorities to treat the long term complications.

In 1778 measles was believed to be introduced into the Pacific islands by Captain Cook’s voyages and has been blamed for the crash of Tahiti’s population from 135,000 in 1820 to around 60,000 a hundred years later. However it was the regular pandemics of cholera that emanated from Asia and spread by maritime trade to the burgeoning slums of industrialising Western countries that provided the impetus for the development of the Victorian public-health movement, leaving an international legacy of institutional arrangements, not least in the UK which was in the vanguard.

The Great Influenza of 1919, ‘The Spanish ’flu’

While accounts such as those by Defoe and Camus provide insights into the social, political and cultural impacts of a pandemic caused by a bacterium, it is the so-called Spanish ’flu of 1918-1920 that provides the first chronicled example of a virus wreaking havoc at a global scale. The most likely origin of what has been called ‘The Great Influenza’ was in the rural and poverty stricken county of Haskell, in Texas, in 1918.

In his comprehensive description of the lead up to the outbreak and subsequent course of the pandemic as it went global, John Barry recounts how a handful of cases of a most virulent strain of influenza were first brought to the attention of Loring Miner, an unusual rural doctor with a taste for the classics.

A man rather in the tradition of the celebrated Wensleydale general practitioner, Will Pickles, who charted the spread of childhood infections such as measles through his country practice in the Yorkshire Dales in the 1930’s, Miner was a medical scientist before such a breed had barely taken root in the US. In January and early February of 1918, he saw a succession of patients who were brought down with violent headaches and body aches, a high fever and a non-productive cough, killing many of them. Dr Miner, who was ahead of his time in having created his own, small laboratory in the practice, explored the blood, urine and sputum of his patients in a desperate effort to identify the causes of the illness, searched the literature, discussed with colleagues, and reported his experience to the US Public Health Service. The latter, according to Barry, offered him neither assistance nor advice. And then the disease seemingly disappeared.

The influenza soon reappeared in a large military camp 300 miles away where thousands of young recruits were being mobilised to join the allied forces in Europe for the final phases of World War I. In a bitterly cold winter and in overcrowded, underheated conditions, where they were huddled together for warmth, these and hundreds of thousands of brother squaddies in many similar camps across the country, had been cooped up waiting for mobilisation.

At the beginning of March, the same clinical picture that Dr Miner had seen in Haskell began to emerge here, and later other camps, and ravaged through the troops. Before long it seems to have travelled with them into the battlefields of France and Belgium and soon impacted on the German troops, if anything with greater ferocity (possibly contributing to their failure to secure victory).

The virus subsequently returned to the US, as it did to all corners of the world, becoming known as the ‘Spanish ’flu’ only because censorship in the field of war had failed to report its Texan antecedents.

The tendency to blame other countries for epidemic diseases is a well-established one, not least when they carry a social stigma as in the case of venereal infection, syphilis most notoriously having been known as French pox in England and the English Disease in France. The habit of attributing geographical labels with political connotations to epidemics of viral pneumonia would be something that would arouse great emotion with COVID-19. By the time of the last Spanish ’flu victim in December 1920, the pandemic had accounted for between 50 and 100 million lives worldwide. A distinguishing feature of the pandemic was that its victims tended to be much younger than those normally affected by influenza viruses.

Barry’s account reminds us that a century ago virology was in its infancy, as indeed was scientific medicine, and that the American medical schools had only recently emerged from domination by quackery and religion with the establishment of Johns Hopkins University in 1876. The Great Influenza provides rich insights into the personalities, characters, competitiveness, strengths and weaknesses, foibles and peccadilloes of many of the giants of American medicine of the times as they struggled to throw light on the nature of the new virus. For much of the time they were thrown off track by the unusual clinical presentation of atypical pneumonia that also affected a range of other organs and systems beside the lungs; something that resonates with the experience of COVID-19, perhaps even now raising questions as to the diagnostic accuracy at that time.

The virus involved in the 1919 pandemic has long been held to have belonged to the influenza group of viruses and therefore different from the coronavirus, COVID-19, but in many ways, in addition to its multi-organ clinical presentations it bears an uncanny resemblance. Not only did the 1918-19 pandemic creep up silently on an unprepared world but its social, political and economic impact provided a foretaste of what the world is grappling with in 2020.

Hesitancy and resistance in the face of a growing emergency, a weak public-health system and a political leader, President Woodrow Wilson, preoccupied by his sense of mission towards Europe, albeit a desire to join the war to defeat Germany rather than a battle for Brexit, distracted attention from the enemy virus within the USA that was biding its time, ready to wreak havoc on an unknowing world.

Wilson’s single-minded focus on the war effort enabled mass gatherings to take place that undoubtedly seeded the initial epidemic around the country, together with a succession of unmonitored marine sea movements of troops and merchant vessels plying between the ports and army camps of the eastern seaboard.

One day we may know whether among the main SAGE advisers to the UK government there was a public-health historian. It doesn’t seem likely.

2 Straws in the Wind

‘Problems worthy of attack, prove their worth by hitting back.’

Piet Hein, Danish polymath

It is crucial to understand the evolution of human urbanisation in order to understand modern epidemics in general and COVID-19 in particular. The history of patterns of health and disease in human populations is intimately bound up with it.

The population of England and Wales in 1086 was of the order of 1.25 million, as estimated in the Domesday Book. For the next 600 years there was slow overall growth, interrupted by dramatic decline caused by the Black Death, and by 1695 the population stood at about 5.5 million. Accurate figures are available from the decennial census that has been conducted since 1801 when the population was nearly 9 million. The population doubled in the first half of the nineteenth century and nearly doubled again in the second half to about 35 million. Over one million British military personnel perished during both world wars. After 1901 the population increase slowed with deferment of the birth of first children, dramatic reductions in family size towards one- or two-child families and a significant proportion of women, perhaps as high as 20%, electing to have no children or being childless at the end of the childbearing years.

What drove the quadrupling? The possible explanations for a change in population size include a positive balance of migration, an increase in the birth-rate or a decline in the death-rate. Historically migration does not appear to have been an important factor until recently, and it is unlikely that the population increase before the middle of the nineteenth century was caused by an increasing birth rate. This was already high and had begun to decline in the latter part of the century; it is more likely that the dramatic increase in population was accounted for by a reduction in death rates, especially among children. Significant immigration of younger workers from Europe and beyond has been the main contributor to increases in the overall population in recent decades.

The overall effect of demographic trends since the World War II, and especially since the 1970’s, has been a dramatic change in the age distribution of the population with many fewer children and young people together with a much greater proportion of people living well beyond the biblical three score years and ten, into their 80’s, 90’s and beyond. These trends have not been distributed equally with corresponding growing gaps opening up in both life expectancy and healthy life expectancy between the most fortunate and the most disadvantaged.

During most of the existence of the human race a large proportion of all children probably died in the first few years of life. The sustained reductions in deaths from the eighteenth century onwards have to a large extent been attributable to reduction in the toll from infectious diseases associated with nutritional and environmental factors. Simply put, healthier nutrition and more hygienic environment shrank the national death-rate from infection for infants. The most important of these have been tuberculosis, chest infections, and the water- and food-borne diarrhoeal diseases.

Paradoxically, it meant that the share of deaths caused by infection grew among the entire population. The predominance of infectious disease as a cause of death probably dates from the rapid urbanisation and creation of urban slums that followed the agricultural and industrial revolutions. In this sense the disturbance of longstanding human habitats with disruption of the relationship between people and their environments, thrown together into overcrowded slums, was critical in creating fertile conditions in which epidemic disease could become established and spread. We see the same in parts of the world that are currently urbanising.

Particularly the underprivileged benefitted from local public-health management. During the nineteenth century, increased food production stemming from changes in agriculture led to significant nutritional benefits and later reduced family size from the widespread adoption of birth control has been a significant factor in improving the prospects of children from poorer households by increasing their share of available resources including food. From the 1840’s onwards the systematic public-health responses of local public-health teams based in the town hall and supported by central government, substantially designed out many of the environmental conditions that undermined healthy living. This was achieved through close working relationships with town planners producing a wide range of initiatives such as slum improvement and the building of council housing, the provision of safe water and sanitation, paving of streets and refuse collection, the creation of urban parks, and wash houses.

Today, all of these are all taken for granted and considered preconditions of a robust economy. But it is good to remember at one point or another, they were controversial public-health initiatives that had to overcome government inertia if not staunch resistance of those who thought they knew better or that the status quo was good enough.

What is remarkable to many is the recognition that, with the exception of vaccination against smallpox, it is unlikely that immunisation or medical treatment had a significant impact on mortality from infectious disease before the twentieth century. In particular, and a most important message when we come to consider COVID-19, most of the reduction in mortality from tuberculosis, bronchitis, pneumonia and influenza, whooping cough and food and water-borne diseases had already occurred before effective immunisation or treatment was available.

To those who think a COVID-vaccine will be the silver bullet this recognition may give some pause for thought. It is only since the advances in scientific medicine and pharmacology after World War II that the contributions from these two fields of endeavour have been able to take their meaningful place alongside those from environmental, political, economic and social measures. Even so, the operative words are ‘take their meaningful place alongside’, not by any stretch of the imagination ‘replace’.

Since World War II the remarkable progress in scientific medicine has delivered huge benefits to population health, not least through the development of an extensive range of vaccinations that have all but eliminated many of the childhood infectious disease...

Table of contents

- Early Praise

- Blinded by Corona

- 1 Plagues in History

- 2 Straws in the Wind

- 3 A Disaster Waiting to Happen

- 4 A Rising Tide in Wuhan, China

- 5 The Virus Arrives in the UK

- 6 News from Bahrain

- 7 A Wasted Month and an Absentee Prime Minister

- 8 A Floating Petri Dish Maggi Morris

- 9 Where There is No Vision, the People Perish

- 10 SAGE

- 11 Left to Die, ‘Herd Immunity’

- 12 Chickens Coming Home to Roost

- 13 The Last Stop

- 14 Politically-Led Science and the Numbers Game

- 15 Lockdown

- 16 The Forgotten

- 17 Dying Matters

- 18 Independent SAGE

- 19 Cummingsgate and After

- Afterword

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary

- Select Bibliography

- Biographies

- Copyright