![]()

Chapter 1

A model of team performance

Big Teams are an essential feature of modern working life. The tasks and challenges faced by people in organizations require the collective skills and knowledge of different people assembled into effective units. Humans have been adept at working cooperatively in groups for thousands of years, but are also equally capable of finding reasons to disagree and disconnect from each other. In the last 50 years or so, leaders and academics have tried to understand the factors that influence a team to achieve results beyond expectations or to fall in to dysfunction. For those interested in teamwork and team development, there is plenty of material to explore. Most of the published research focuses on the dynamics occurring within a small team, usually containing five to ten people. The research also tends to concentrate on static teams working in permanent organizations where a team is regarded as a unit of the organization’s structure.

There is relatively little information on another significant segment of the working population world, which operates in the world of projects. Project teams have a different set of internal dynamics, which can both positively and negatively affect how they function. Projects come in many shapes and sizes, some requiring the attention of perhaps a dozen or so people, whilst others may require the skills of thousands. As we move through the change and upheaval of the 21st century, projects are growing in scale, being driven by governments upgrading a country’s infrastructure or commercial businesses seeking to take advantage of new opportunities that may have global reach.

Large projects require many people from different professional, technical and social backgrounds to come together and work as a cohesive entity, which can be called a Big Team. The book is written for those who must lead, manage and deliver large projects in which people are assembled in a continually shifting organization structure. The content is therefore focused on how a project or programme is organized and influenced when the number of people involved grows beyond the scale and control of an individual leader. Should you decide to invest some time in learning, you will find there is both an art and a science to the development and maintenance of a Big Team. We will be exploring some of the technical structures and processes that are a part of the organization of a major project but the primary focus is on leadership, and the factors that shape and influence successful Big Teams.

Projects vs business-as-usual

The following chapters are primarily focused on the distinct challenges of working on major projects. The content is less concerned with teams working on day-to-day operations often referred to as business-as-usual. Many enterprises employ large numbers of people to carry out the different functions that the organization needs to deliver its intended purpose. Business-as-usual teams are generally set up as a collection of distinct functions designed to produce specified outputs on a repetitive basis. Over time these functions develop their own distinct subcultures, which tend to limit communication and collaboration with other departments. Whilst the leaders of large permanent organizations might aspire to their staff working as a unified entity, the reality of day-to-day life means that they default to siloed entities, each with their own goals and agendas that rarely translate into a cohesive whole. As we will see, large project teams can also struggle with siloed behaviours, but every new project has the opportunity to establish the right behavioural norms without having to undergo a major transformational change initiative.

It is a frequent observation in the project management literature that projects create temporary organizations, which have a number of characteristics that separate them from permanent organizations. Ana Tyssen and her colleagues Andreas Wald and Patrick Speith (2013) set out a number of factors that illustrate this difference:

1. Projects usually have a limited and predefined duration, which compresses the time available to develop the strong cultural norms that are needed to build trust.

2. Large projects invariably have a unique outcome and must rely on creativity and technical knowledge within a set of participants who have only a limited time to get to know each other.

3. Project teams will often have missing hierarchies so that there are gaps or overlaps in authority.

4. Finally, major projects have a high level of uncertainty, creating greater risks, which in turn can reduce commitment when events do not work to plan.

This distinction between permanent and temporary organizations is important. As discussed above, the whole concept of leadership is recognized as a critical success factor to any enterprise that seeks to coordinate the activities of large groups of people. Each of these factors creates distinct challenges for those tasked with leading a project. As complexity within the project environment increases, the limitations imposed by the temporary organizational structure become more critical to the project’s performance. Most very large projects are actually made up of a programme of works but, for the sake of brevity, I have used the term project to cover both terms.

This does not mean that the contents of this book are irrelevant to business-as-usual teams in permanent organizations. Whilst the challenges of introducing a cohesive culture within a permanent existing organization are quite distinct from those of the project, humans working in groups present the same managerial problems whatever the focus. The concepts and ideas set out in this book therefore apply to many of the situations found in permanent organizations, although obviously the context will differ.

There are a number of core themes that inform the observations, ideas and suggestions contained in the subsequent chapters:

1. a Big Team as a team of teams;

2. the three primary elements of a project;

3. the impact of complexity and uncertainty on major projects; and

4. the behaviours of humans working in groups.

I will now look at each of these in turn.

A Big Team as a team of teams

Before we continue, it is worth exploring what I mean by a ‘Big Team’. It is not easy to find a definition of what constitutes a ‘big’ or a ‘large’ team. The word team tends to be used in the world of projects to include every person engaged on that project and often crosses organizational boundaries. In this context, it is simply a noun used to delineate anyone who may have an active interest in the undertaking. It is often intended to show a degree of inclusivity but the reality is that, as the numbers of people engaged in a project increase, there is not a single big project team, but rather a collection of small teams.

There is an important distinction to be made between big and small teams. These simple words explain a much deeper concept. Terms such as small and big are part of our basic language. They can therefore be seen to be generic, having such a wide range of application. In the context of teams, however, these two words have a precise technical role that helps establish some key differences. To emphasize the distinct nature of a Big Team, I will continue to capitalize the term throughout the book.

The small team is the unit of production within any large enterprise. Emperors and generals have historically organized their armies and administrators into manageable groups. This is not, however, a top-down management strategy to create neatly arranged grouping on an ‘org chart’. It is actually a reflection of how humans prefer to work with each other. Groups of people naturally fall into sub-groups as the numbers involved start to increase. This is partly because we can typically engage on a regular basis with up to ten people, but beyond that number, communication starts to become more sporadic and building close working relationships is more difficult. In terms of size, Michael West (2012) confirms a commonly held view that effective teams contain fewer than 15 people, and ideally 6–8. It is not possible to define at what point a ‘normal’ team becomes a Big Team, as the distinction will be specific to the context of the situation. However, as projects scale up in terms of scope, budget and programme length, more people become involved, and will quickly reorganize themselves organize into sub-teams that might be based around function, specialization or just personal preference.

Large projects evolve over time. They typically begin with a core group that takes the project through its preliminary stages, but then the numbers expand rapidly when the programme moves into detailed planning, design and delivery. Some teams come from one organization but major projects also usually draw in many small specialist teams. Some of these small teams are collections of individuals who have worked together before, but others will be newly formed. Whilst every major project has a distinct culture, which affects how it works, each small team will develop its own subculture. This is driven by the team’s leaders, by the circumstances of the project and by the other social or commercial elements that tie them together.

The point is that Big Teams do not exist as a single homogeneous whole, shaped by a unitary corporate culture. Instead, a Big Team is an organic collection of individuals and small groups whose roles and activities shift and change as the project they are engaged on progresses. Project success therefore depends upon the extent to which the leadership can enable this assembly of small teams to work effectively together as sub-units that make up a single Big Team.

The danger in writing about projects as a generic term is that the text can lose the nuances and practical observations that are specific to an industry sector, or particular type of project. When exploring the challenges of a software team, the technical processes used will typically be different to those used on an engineering project. When it comes to understanding the behaviours within project teams, however, the primary challenges are very similar. Humans are wired to operate using patterns of behaviour that are, to a certain extent, quite predictable depending upon various factors that shape how they operate as a group.

The three primary elements of a project

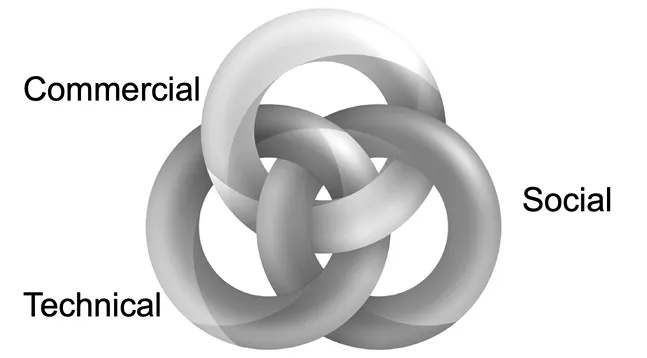

Having spent much of the last seven years studying team working on large projects, I have found there are three primary elements to every project, each requiring a distinct area of competence:

• Technical competence – the knowledge and awareness of how components of the project are to be designed and assembled.

• Commercial competence – the knowledge and awareness of issues around money, contracts and the identification and management of risk.

• Social competence – the knowledge and awareness of how humans behave in groups and teams.

Technical competence comes from the years of investment in education and training in a particular profession that an individual chooses as the basis for their future career. This knowledge stays with us as we move from project to project, building as we add new experiences that improve our practical application. Large project teams typically comprise a wide range of specialist professionals each providing a distinct contribution to the design and delivery of the project. Not surprisingly, this is where much of the focus on team selection takes place.

Figure 1.1 The three elements of project competence

Technical skills alone are not sufficient as someone must take care of the money. Whether the project is sponsored by a public or private body, the team must pay attention to commercial matters. Budgets must be created and costs monitored. The risks to the project must be identified and mitigated, and processes must be put in place to ensure the governance of the project follows best practice. Project sponsors usually apply considerable resources in the form of lawyers and accountants to ensure that sufficient commercial intelligence is in place.

The third, but least articulated, element is social competence. This capability is critical ...