![]()

PART ONE

People made into patients

![]()

1

To screen or not to screen: first do no harm

Is it possible to be in perfect health? Not any more. The only normal person is one that that hasn’t had modern medicine unleashed on them. Take a perfectly well person and run blood tests, scans, X-rays or bowel tests – and there may be a blood level that’s above average, a possible hint of a shadow on a scan. Still feeling well, still in perfect health? Alas, our collective love-in with too many medical tests has run away with our common sense and produced a big problem. The screening of people for disease causes enormous problems which don’t often get acknowledged – not even to the people having the tests.

This is medical screening in action. Screening tests don’t involve people who are ill or have symptoms. First off, if you are ill, you need to be checked out. This is not screening. If you have a lump that worries you, a tendency to collapse without warning, an itch that won’t go away or any other complaint about your health, you are symptomatic. Symptoms need sorting. Generally, that means seeing a doctor who will take ‘a history’, giving you time to describe and explain what is happening. So: ‘For the past three months I’ve had this itching under my skin so bad that I scratch myself until I bleed. I can’t think why, but it’s worse after a shower.’ The doctor asks you questions designed to hone in. Have you been abroad? Anyone else itchy? Anything new you’re putting on your skin?

He is then meant to examine you, looking for a rash or evidence of infestation with lice or scabies, or other lovely creatures. The diagnosis may not be definite and tests may be needed to increase the certainty – a skin scraping or maybe a blood sample. Finally, diagnosis is followed by treatment, with follow-up to ensure that all is going to plan and that the side-effects of treatment are not disabling or worse than the condition.

Screening is not about sorting out ill people. Many politicians and, sadly, some people who work in healthcare don’t understand this. So, for example, breast screening is offered to women who have no complaints of breast lumps. Depression screening is offered to people who are not complaining of mental ill health. Screening is not about working out what is going on when, for example, a woman complains of chest pain or a man confides that he has suicidal impulses.

The difference is important. I’ve had angry emails from people telling me that if they hadn’t got ‘screened’ they’d be dead. Often, though, those people had not been screened – they had been diagnosed on the basis of symptoms. It’s very different.

So, if you are a man with no complaints about your ability to urinate or copulate, are feeling hearty but decide you’d like a prostate check-up anyway, you are embarking on the process of being screened.

The ethical practice of medicine means being honest about the limitations and potential harms of interventions as well as the benefits. And as for what Hippocrates said...

‘First do no harm’

Screening throws Hippocrates out of the window. We have no screening test without side-effects. Harm is inevitable. With any screening programme, the gamble is taken that ultimately, it will cause more good than harm. This is the essence of why screening is difficult and can be summed up in a beautiful and counterintuitive puzzle. Try this:

A disease affects 1% of the population. It is fatal. There is no treatment. The test for this condition is 90% accurate. So if you test positive for the disease, how likely are you to have it?

Most people read this question and say that you are 90% likely to have the dreaded disease, and agree that your priority is now writing your will and working out what your last wishes are. It seems logical: the test is 90% accurate, so that’s how likely you are to have the disease.

It’s also wrong. The ‘90% accurate’ bit refers to how likely you are both to have the disease and test positive for it. So if you have 100 people with the disease, only 90 of them – 90% – will test positive for it.

This is the crunch. If you are being screened for the disease, which only affects 1% of the population, then you only have a risk of 1% of having it.

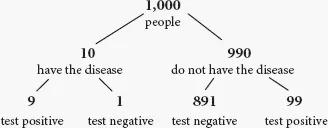

Let’s make the numbers easy. Say we have 1,000 people, and ten of them – 1% – have the disease. If the test is 90% accurate, it will pick up nine of them. One person will test negative even though he has the disease.

But that test is also 90% accurate for the people who do not have the disease. This means, that out of the 990 people who don’t have it, 99 will end up testing positive for a disease they don’t have.

The accuracy of screening results

The accuracy of screening results in 1,000 people, where the test is 90% accurate and the disease affects 1% of the population.

So in total, out of that 1,000 people, 99+9 people test positive, 108 in total.

But only nine of those people really do have the disease.

So if you test positive for this disease, your chance is only nine out of 108 that you really do have the disease – about a 10% chance.

The first time I learned about this I remember being very shocked. How could a pretty good test – 90% accurate! – be so rubbish?

It’s mainly because the risk of having the disease is still pretty low. If you run a test in someone who has a high risk of having the disease – for example, if you are running the same test in a population where 50 of 100 people have the disease, not one in 100 – the odds of the same test being more accurate will increase. But when we are screening for disease, we are usually looking for things that are relatively rare. Thus starts the difficulty in making sure that testing positive for a disease is a reliable sign that you actually have it.

Certainly there are rare screening tests that are useful, for example the Guthrie test, which is done in newborn babies to detect metabolic problems that can be treated before brain damage is done. It’s one of the best screening tests on offer, but even then, a positive test result is only verified in a minority of cases.

Remarkably, and sadly for most medical check-ups, a positive test often means a problem with the test, not the patient. This causes harm because in order to know who truly has a disease and who does not, further tests are required. These can be anxiety provoking, and can cause harm within themselves.

The problems with screening

Why do we not screen, for example, for brain tumours? Brain tumours are serious, and can cause death and disability. Why do we not want to ‘catch them early’?

Criteria for what makes a good screening test were established by the World Health Organization in 1968.1 For example, there is no point screening for a disease for which you don’t have a great solution. If you screen for and then find 1,000 cases of an incurable disease, as some brain tumours sadly are, then you haven’t helped very much – all you have done is identified some tumours earlier. You could argue that this is a bad thing. It’s certainly not useful.

Useful screening means finding an unsuspected disease at a stage where you can treat and, ideally, cure it. A perfect screening test would be one that was always right, neither invasive nor unpleasant, with a cure that was always successful and with no side-effects. Welcome to la-la land.

WHO definition of screening tests

1. The condition sought should be an important health problem.

2. There should be an accepted treatment for patients with recognized disease.

3. Facilities for diagnosis and treatment should be available.

4. There should be a recognizable latent or early symptomatic stage.

5. There should be a suitable test or examination.

6. The test should be acceptable to the population.

7. The natural history of the condition, including development from latent to declared disease, should be adequately understood.

8. There should be an agreed policy on whom to treat as patients.

9. The cost of case-finding (including diagnosis and treatment of patients diagnosed) should be economically balanced in relation to possible expenditure on medical care as a whole.

10. Case-finding should be a continuing process and not a ‘once and for all’ project.

Wilson JMG and Jungner G, World Health Organization, Geneva, 1968

There is no such thing as a perfect screening test – not that you’d know from the sexed-up inducements, incitements and fervour attached to screening in the UK.

The myth of the body MOT

One of the great Harley Street sells is the medical ‘check-up’. Even smart people equate our bodies to cars requiring MOTs at least once a year. Competing clinics, many operating in chains, offer testing packages that are described in terms that may seem better suited to first-class airline travel or gym memberships: ‘premium’, ‘ultimate’ and, bafflingly, ‘ultimate plus’. These check-ups will cost you from hundreds to thousands of pounds and are designed for people who want to ‘take control’ of their health and won’t mind spending a few hundred or thousand pounds for the treat. Prescan, a company working out of Harley Street, says that ‘a preventative examination will enable you to find out in time or just to get some certainty regarding your health’.2 Lifescan has worked ‘in partnership’ with Tesco Clubcard to offer you a ‘check for the very early signs of heart disease, lung cancer, colon cancer, aneurysms and osteoporosis as well as other illnesses’.3

Well, we are all at risk of dying. These companies want you to believe that the check-up will heroically save you from death. Either you will be reassured that everything is fine and this knowledge, despite its effect on your bank balance, will cheer and sustain you. Or you will have your cancer or heart disease diagnosed. You have it spotted early. You are still a winner. It may seem as though this is a bet that wins each way. If the test is ‘all-clear’, then you can feel pleasure and relief. If the test shows a problem, you can feel virtuous in knowing that your proactivity has saved you from your early fate.

Sadly it’s not true. We are not cars. The clinics are offering screening tests, which do not obey superficially logical assumptions. Instead, screening tests are complex and their outcomes are often counter-intuitive.

Still, it’s hard to emphasise the absence of evidence when you get tales of salvation through the whole body MOT, such as this, from the front page of the Prescan website:

‘Prescan’s MRI revealed a two inch kidney tumour – if it had been left unchecked my story would have a very different ending!’

Or, from the celebrity-packed Preventicum testimonial webpage:

‘My check-up was far more thorough than I had anticipated and the doctors detected a brain aneurysm as a result of my MRI scan. This came as a complete shock to say the least. Luckily, thanks to Preventicum, it was detected early enough to be successfully treated and I was back at work less than three months after the surgery. I wholeheartedly recommend having this check-up, whether you have a specific concern or just want to find out how healthy you really are. Preventicum certainly saved my life.’

Magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, and high-resolution CT (computerised tomography) are the best in modern medical imaging. What was a blurry snowstorm 50 years ago is now rendered in three-dimensional digital clarity, shining pictures of kidneys, livers, lungs and brains onto monitors seconds after scanning. Modern equipment is smaller, quieter, and less intimidating. The private check-up sector – and they accept most credit cards – has erupted as these scanners have become cheaper and better in quality.

Scams and scans

The fact that there is so much choice about what kind of deluxe health check to have is a pointer to the problem at the heart of the scanning-on-payment industry. You can have any number of permutations of imaging: a lung check, a colon check, a heart scan, a bone mineral scan, a brain scan or womb or prostate scan. Most companies are keen to stress that they’ll make adjustments to pricing structures according to your desire. Hey, it’s a customer thing.

These clinics are often owned by medically qualified doctors. Some are not and just have doctors working there. Doctors are required because of the regulation controlling ionising (X-ray) radiation. With doctors on board, the clinics appear more legitimate, honourable and regulated, offering a responsible way to execute your responsibilities to your health, pleasing to the ‘self-care’ mantra, and, overall, a good way to spend your time and cash.

It would be reasonable, therefore, to expect some evidence supporting this kind of screening. Proof of usefulness that might mean there is a chance that the scans would be better for your health than, say, running away from these clinics at top speed with your cash still in your pocket.

Here’s the story of Brian Mulroney, the former Canadian Prime Minister, as told to me by H Gilbert Welch, public heath doctor and author of Should I be tested for cancer? Maybe not and here’s why.4

‘In 2005, he went to the doctors for a routine check-up. As part of the check-up, he had a spiral CT scan. It showed two small, but worrisome nodules. He had surgery to have them removed. Postoperatively, he developed pancreatitis – a complication of surgery.’

The nodules, which were on the lung, had been removed, but Mulroney had to be moved into the intensive care unit of the hospital.

‘After a month and a half in the hospital, he was discharged to convalesce at home. Then he had to be readmitted a month later to have an operation on a cyst that had developed around his pancreas – a complication of pancreatitis. He was in the hospital another month. Oh, and he didn’t even have lung ca...