![]()

1

The history of medicine in the light of the history of plastic

It happened on Tuesday November 1, 1949. In the morning of the very first day of my medical studies, I was introduced in the surgical unit of Hôpital Cochin, in Paris. Younger doctors might find it strange that French students my generation were abruptly in touch with the real world before learning from textbooks of anatomy, physiology and pathology. One of the effects of starting a medical career that way is a clear memory of what a huge hospital common bedroom looked like in the middle of the twentieth century. I can remember in particular that during the six months I spent in that surgical unit I never saw a patient whose arm was connected to a bottle.

I became familiar with drips during the first months of 1952, in a medical unit specialising in the treatment of lung tuberculosis. Then two recently discovered effective drugs were routinely associated: streptomycin and PAS (p-aminosalicylic acid). PAS was administered intravenously from a glass bottle via a rubber tube connected to a steel reusable needle. After that, during the winter 1953–1954, I never saw a labouring woman receiving an intravenous treatment during the six months I spent as an externe (medical student with limited clinical responsibilities) in the maternity unit of Hôpital Boucicaut. The first obvious reason was that synthetic oxytocin was not available: it was precisely in 1953 that Vincent du Vigneaud established its chemical formula and made its synthesis possible. Another reason was that childbirth was not yet highly medicalised: a maternity unit, even in an avant-garde Paris hospital, was not the right place to detect the first signs of the plastic revolution, although it was the very time when polymer chemists were finding new compounds almost weekly, engineers were constantly improving medical equipment, and ethylene oxide (ETO) sterilization was proven effective and non-harmful to plastics. It is only during the second half of the 1950s, when trained as a surgeon, that I started to realise the importance of plastic in modern medicine.

I participated in a new phase of the plastic revolution when in the French army, during the War of Independence in Algeria, in 1958–1959. The history of emergency surgery always went through spectacular new steps during wars. At that time all the tubes were in plastic. Polyethylene tubes were widely used. I became familiar with the technique of ‘venous cutdown’, as an emergency procedure making possible massive fast blood transfusions: through a one-centimetre incision at the level of the ankle, the great saphenous vein was exposed surgically and then a polyethylene tube was inserted into the vein under direct vision.

The history of medicine during the past fifty years cannot be dissociated from the history of the use of plastic material. Disposable medical devices developed gradually after 1960. Around 1970 plastic bags were introduced, thus reducing the risk of air embolism. New plastics, less and less traumatic to veins, replaced polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Around 1970, there was the Teflon revolution, followed in the 1980s by the polyurethane revolution. The use of intravenous drips became so widespread in modern hospitals that the procedure of intravenous cannulation became gradually the business of nurses and midwives, while it was originally the business of doctors. Advances in the medical use of plastics have induced a new phase in the relationship between doctors, nurses, and midwives. Today there is a new realm for specialised doctors. It is to introduce plastic tubes in any vessel, in any organ, and in parts of the body that until recently were accessible only through direct surgical routes.

Plastics have transformed most medical disciplines. For example, anaesthesiologists were traditionally experts in the administration of inhaled drugs. After the turning point in the history of medicine they became experts in the use of intravenous and epidural routes: what a mutation! We might establish a catalogue of the numerous medical specialties that were radically transformed by the evolution of plastics.

The development of plastics has not only transformed most medical disciplines; it has also made possible the emergence of new specialties, such as neonatology. In the middle of the twentieth century, paediatricians were occasionally asked to take care of newborn babies. Today neonatologists share the activities of departments of obstetrics and there are intensive care units for newborn babies. In such units most babies are in a plastic incubator, with plastic catheters introduced in big veins and in natural orifices. In general the very concept of intensive care is a consequence of the medical use of plastic material.

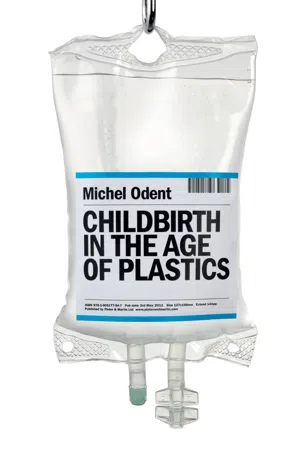

The plastic revolution has had spectacular effects in maternity units. It was the prerequisite for the current standardised medicalisation of childbirth. Today it is commonplace to visualise a typical labouring woman as a woman whose arm is connected to an IV plastic bag via a plastic tube, while a catheter has been introduced in her epidural space. People my generation can easily realise that this is an absolutely new situation. When we are in an unprecedented situation, the priority is to phrase appropriate new questions.

![]()

2

Unasked questions about the most common medical intervention in childbirth

A labouring woman was inquisitive and even anxious when she received a drip of synthetic oxytocin. The midwife immediately reassured her that oxytocin is not like a drug: it is “natural”. Perhaps this is why there are many unasked questions regarding what is undoubtedly the most common medical intervention in childbirth on all five continents. Let us recall that oxytocin is considered the main birth hormone, first because it is necessary to induce and maintain effective uterine contractions for the birth of the baby and for the delivery of the placenta, and also because it may be presented as the main love hormone. Today, all over the world, most women giving birth vaginally get such a drip (called Syntocinon or Pitocin) including those with an eventual operative delivery by forceps or ventouse. Most women who undergo a caesarean section during labour have had such a drip before the decision to operate, and this drip is usually continued for some hours after the surgery. Even during and after a pre-labour c-section, synthetic oxytocin is included in many hospital protocols to facilitate uterine retraction. Furthermore, the rates of labour inductions are currently high, and induction almost always involves the use of synthetic oxytocin.

Preliminary questions

This new situation raises important questions. We must first wonder why modern women need substitutes for the hormone that is naturally released by the posterior pituitary gland. Is it because their oxytocin system is disturbed? Is the capacity to effectively release oxytocin depleted from generation to generation, as a result of several aspects of modern life, particularly medicalised birth? This is a vital question for the future of civilisation, since the oxytocin system is involved in sociability, capacity to love, and potential for aggression. Is it mostly cultural conditioning in a context of industrialised childbirth? In this latter case the current situation might be reversible. If it is simply a matter of environment at birth, we need to improve our understanding of the birth process. In fact, we must explore the possible contribution of multiple factors.

Other questions address the substances that might cross the placenta and reach the unborn baby. For example, the kind of fluid used to transport synthetic oxytocin. In earlier times, glucose drips were routine during labour. These infusions were not benign because simple sugar molecules rapidly cross the placenta while the mother’s insulin – released in response – fails to reach the fetal bloodstream. There is thus a risk of excessive insulin production generated by the baby’s pancreas in response to these circulating high blood sugar levels. Extensive research has confirmed the risks of neonatal hypoglycemia.1–7 These studies led to the replacement of glucose drips during labour by other liquids, such as Ringer’s solution. The results of such studies also apply to labouring women without a drip of synthetic oxytocin if they are encouraged to consume sugar or soft drinks. This is not always understood by the natural childbirth groups. Furthermore, if labour progresses spontaneously, adrenaline-type hormone levels are low, voluntary muscles are at rest, and these women do not need added energy.8

Can synthetic oxytocin cross the placenta?

When we finally acknowledge that all over the world most women receive synthetic oxytocin while giving birth, we can no longer deny problems arising from the possible transfer of oxytocin via the placenta. One can wonder why it remains an unexplored issue. The main reason, as we have suggested, might be that oxytocin is not considered a “real” medication because chemically the synthetic form is no different from the natural hormone: it is a simple molecule (a nonapeptide). However, the problem is not simple because the amount of oxytocin reaching the maternal bloodstream via an intravenous drip is enormous compared with the amount of natural oxytocin the posterior pituitary gland can release. Furthermore, natural oxytocin is released through pulsations, while synthetic oxytocin is delivered continuously. Another reason for ignoring this issue might be the discovery of enzymes that metabolize oxytocin (oxytocinases) in the placenta. This finding might have led to a hasty, tacit conclusion that synthetic oxytocin does not reach the baby.

Until now, there has been only one serious article published on this subject.9 A team from Arkansas concluded that oxytocin crosses the placenta in both directions – after measuring concentrations of oxytocin in maternal blood, in the blood of the umbilical vein and umbilical arteries, and also after perfusions of placental cotyledons. More precisely, the permeability is higher in the maternal-to-fetal direction than in the reverse. Eighty percent of the blood reaching the fetus via the umbilical vein goes directly to the inferior vena cava via the ductus venosus, bypassing the liver, and therefore reaching the fetal brain immediately: it is all the more direct since the shunts (foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus) are not yet closed.

Since there is a high probability that a significant amount of synthetic oxytocin can reach the fetal brain, we must investigate the permeability of the so-called blood-brain barrier at this phase of human development. This “barrier” implies a separation of circulating blood from cerebrospinal fluid in the central nervous system. It restricts the diffusion of microscopic particles, including bacteria, and molecules such as oxytocin. However, Australian researchers presented evidence that the developing brain is more permeable to small lipid-insoluble molecules and that specific mechanisms, such as those involved in the transfer of amino acids, develop gradually as the brain grows.10 In general, there is an accumulation of data suggesting that the blood-brain barrier works in a specific way during fetal life.11–14 Furthermore, it appears that the permeability of the blood-brain barrier can increase under the influence of oxidative stress,15–17 that commonly results when a synthetic oxytocin drip is administered during labour.18 Therefore, we have serious reasons to be concerned if we consider the widely-documented concept of “oxytocin-induced desensitization of oxytocin receptors”.19–22 It is probable that, at a quasi-global level, we routinely interfere with the development of the oxytocin system of human beings at a critical phase for gene-environment interaction. Within the framework of accepted scientific knowledge, we must acknowledge the important role of oxytocin, particularly in sociability, the capacity to love (of others and love of oneself), as well as the potential for aggression (aggression towards oneself and towards others).23 Interfering in normal reproductive physiology raises critical issues. For example: “Is there a link between the increased incidence of disorders associated with documented alterations of the oxytocin system (such as autism24, 25 and anorexia nervosa26,27) and the widespread use of intravenous drips during labour?” “What will be the impact on the evolution of our civilizations?” We may even wonder if the widespread use of synthetic oxytocin can induce an unprecedented cultural revolution.

Such questions should inspire a new generation of research.

Let us add that twenty-first century technical advances might oblige us to rephrase many questions. For example, it is possible that in the future a drug such as misoprostol (a synthetic prostaglandin analogue given orally) might compete with intravenous synthetic oxytocin.28

![]()

3

Unsuited birth statistics

Imagine a woman whose labour has been induced. After induction she spent hours attached to a drip of synthetic oxytocin with or without epidural anaesthesia. If there was no use of forceps or ventouse, this birth will be classified as “spontaneous” or “normal” in public health reports and studies published in the medical literature. The drips of oxytocin are obviously considered minor details which are not worth mentioning in statistics. The traditional contents of bi...