eBook - ePub

Childbirth without Fear

The Principles and Practice of Natural Childbirth

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

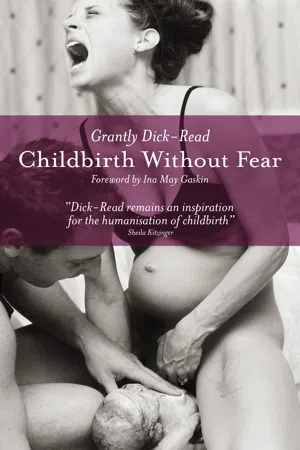

In an age when normal birth can still be overtaken by obstetrics, Grantly Dick-Read's philosophy is still as fresh and relevant as it was when he originally wrote this book. He unpicks the root causes of women's fears and anxiety about pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding with overwhelming heart and empathy. As one of the most influential birthing books of all time, Childbirth Without Fear is essential reading for all parents-to-be, childbirth educators, midwives and obstetricians! This definitive reissue includes the full text of the fourth edition, the last completed by Grantly Dick-Read before his death in 1959, and The Autobiography of Grantly Dick-Read, compiled from his writings.

With a foreword by Ina May Gaskin.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Childbirth without Fear by Grantly Dick-Read in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Gynecology, Obstetrics & Midwifery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Medicine1

The Science of Obstetrics

Before we embark upon this rather hazardous voyage – the description of a new approach to obstetrics – it may be well to outline briefly certain facts relating to childbirth during the later stages of civilisation.

There is a tendency in these days, when publication in the Press familiarises the man in the street with the most dramatic exploits in the laboratory, to accept each new discovery as ‘the last word’. So wonderful do the revelations of science appear that the idea of introducing simplicity as a means of unearthing the even greater revelations of nature is not well received. But let us consider the position today compared with a hundred years ago, and with a thousand years ago. It will then become obvious that there is no reason to suppose that we have done any more in our time than add to our knowledge of childbirth. There is certainly no cause to consider that knowledge perfect.

Humanity has existed for a vast number of years. It is believed that the Neanderthal race lasted for more than two hundred thousand years. There is further evidence that men have lived and died in Europe for over a hundred thousand years. If we accept the Darwinian theory of evolution, the change from man-like apes to man himself is difficult to assign to any given period; but the essential fact remains that the function of reproduction of these species has not altered so far as the fundamental anatomical and physiological machinery is concerned. We still read that the pain of childbearing always has been the heritage of women because nothing in our modern teaching has enabled us to prevent it. It is believed because it has existed. Science of today can relieve women of their suffering, but only in recent years have the causes of pain in childbirth been explained. This has made it possible to prevent and avoid the unbearable discomfort of parturition. It is not without interest that the more civilised the people, the more the pain of labour appears to become intensified.

Since merciful relief of suffering is one of the greatest duties that physicians can perform, it has been easier to utilise the pain-relieving discoveries of science than to investigate its complicated causes. There can be no more horrible stigma upon civilisation than the history of childbirth. This is not a reference only to the unavoidable pains which accompany pathological states in reproduction, but to the most normal and natural parturition. The higher the civilisation of a country the more generally is pain accepted as a symptom of childbirth.

Efforts, of course, have been made to relieve this pain for many centuries. Old writings suggest that herbs and potions were used to relieve women in labour. Witchcraft was resorted to often very successfully. Three thousand years before Christ, the priests among the Egyptians were called to women in labour. In fact it may be said with some accuracy that amongst the most primitive people of which any record exists, help, according to the customs of the time, was given to women in labour. In the Book of Genesis, third chapter, sixteenth verse, ‘The Lord God said to Eve – “I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children.”’ This translation of the holy book to the effect that a woman, because of her sin, was condemned to a multitude of sorrows and pains, particularly in the conception, bearing and bringing up of her children, has had a very considerable influence among Christian communities.

Even as late as the middle of the nineteenth century this was quoted by clerical and medical authorities as justification for opposition to any active relief of the sufferings of women in labour. In the fifth century before Christ, the great Hippocrates endeavoured to organise and instruct midwives. Their attentions bore little resemblance to those which are expected of midwives today, but according to their ideas of assistance so they practised.

In the second century after Christ, Soranus of Ephesus practised midwifery; it is recorded that he not only denied the power of spirits and superstitions, but that he actually considered the feelings of the woman herself (Howard Haggard, Devils, Drugs and Doctors, Heinemann, 1929).

In the Middle Ages, however, women appear to have been deserted once more. In many countries it was a crime for men to attend women in labour until the sixteenth century. Less than three hundred years ago, physicians commenced the practice of midwifery in Europe. It was not until the nineteenth century that the foundations of our present knowledge were laid. We must, therefore, realise how young and how immature is the science of obstetrics. Until the middle of the nineteenth century there was no anaesthesia; it had not been discovered. Until 1866 there was no knowledge of asepsis. It is difficult for people to visualise the state of affairs when limbs were amputated, abdomens opened, and caesarean sections performed without any anaesthesia and with an almost sure supervention of sepsis which gave rise to a high percentage of mortality in the simplest of operations.

In 1847, Simpson first used anaesthesia. On April 7th, 1853, John Snow anaesthetised Queen Victoria when Prince Leopold was born. For the use of anaesthetics for this purpose, Simpson was harshly criticised by the church. To prevent pain during childbirth, he was told, was contrary to religion and the express command of the scriptures; he had no right ‘to rob God of the deep, earnest cries’ of women in childbirth! But anaesthesia had come to stay. A year later, in 1854, Florence Nightingale was the first woman to make widely known that cleanliness and fresh air were fundamental necessities of nursing. It was largely because of her work during the Crimean War that the standard of both the training and the practice of nursing was raised. The gin-drinking reprobates who were found in great numbers both in hospitals and among midwives began to disappear. With their exodus, childbed fever less frequently occurred in midwives’ cases. In the Maternity Hospital in Vienna, medical students’ cases showed an average over a period of six years of ninety-nine deaths per thousand from puerperal fever. Semmelweis, who was physician at the hospital at the time (1858), believed the cause to be due to something arising within the hospital, and made his students wash their hands in a solution of chloride of lime. In one year the death rate in his wards tumbled from 18 per cent to 3 per cent, and soon after to 1 per cent. This success necessitated his facing opposition and hostility from those around him. But his work was done; he had laid a great foundation stone of safer childbirth. Although he did not fully understand the significance of the infection he realised that it was the physicians themselves who caused the deaths of their patients by transmitting it.

Probably all of us pause to think sometimes of how much harm we do in our efforts to do good; how much trouble we cause when conscientiously endeavouring to prevent it.

In 1866, Lister brought us the knowledge of antiseptics, which he continued to employ in spite of the opposition and ridicule of his colleagues.

So, gradually, truth has been discovered; the safety of women has been the object of investigation with results that would have been unbelievable when the mothers and grandmothers of many of us were born. But how short a time we have had – less than a hundred years, and man has been reproducing his kind for several thousands of years. Now that many of the troubles and dangers have been overcome we must move on, not only to save more lives, but actually bring happiness to replace the agony of fear. We must bring a fuller life to women who are called upon to reproduce our species. The joy of new life must be the vision of motherhood, instead of the fear of death that has clouded it since civilisation developed.

It will be easier, therefore, in reading the succeeding chapters, to realise that they represent an effort to improve, an effort to construct new ways and means, not simply to destroy those which have done good service in the course of progress. Therefore, where there is obvious truth in this teaching, let it be augmented; and if any obvious fallacy is unmasked, assist in its burial.

When I wrote these words in 1940, my wildest and most ambitious hopes would not have allowed me to visualise what has actually happened in twelve years. No fallacies have been unmasked and no burial of a single tenet has taken place. This theory has not been found wanting and no criticism has been justified by experience. Vast numbers of women have found comfort and safety in this approach to childbirth. The sordid melancholy of prospective motherhood has been replaced by fearless and impatient longing for the moment of life’s most satisfying achievement. No longer do the trembling hands of women stretch out to seek deliverance from the sorrows of death that compassed them. The science of obstetrics is on a new and higher plane. Motherhood offers all women who have the will and the courage to accept the holiest and happiest estate that can be attained by human beings. That we, as obstetricians, can help and guide them, is our greatest privilege, for with each succeeding generation we may establish the foundations of a new race of men with a clear vision of the future, that holds a practical philosophy and a purpose worthy of fulfilment.

2

Motherhood from Many Points of View

Let us digress for one moment from the science of pure obstetrics and consider the woman herself. Biologically motherhood is her desire and her ordained accomplishment but this apparently physical function goes far deeper and has greater importance than the purely mechanistic production of a child. A mother is a member of society with an intrinsic worth and she occupies a certain status in both the home and the community. If there is one characteristic more desirable to be maintained in communal life, it is the dignity of motherhood. Those of us who have known it from personal experience in our own homes, or from professional associations, visualise it in those calm, competent, and companionable women who live to a great age, acutely sensitive to, but unshakeable by either the cruelties or the rewards of having lived. Motherhood unfortunately does not receive the consideration that it deserves and is justified in expecting. It may be in the modern world that such thoughts are altruistic, but in the outpatient departments of hospitals and in clinics, mothers of families and young girls who are pregnant for the first time, are too often subjected to a surprisingly rigid discipline and impersonal regimentation. How sore or how submissive many of these responsive women become. They do not desire preference among their sisters who are not pregnant but they hope and many yearn for the companionship and comfort of a word of encouragement and confidence from those who in authority examine and dispose of them.

There is war between man and woman for the possession of motherhood. It is a prize of incalculable value for the church, politicians and the doctors.

The leaders of all manner of religious organisations, sects, and denominations recognise the holiness of motherhood and the basic value of the newborn child. We do not forget the significance of Christmas or the manger in the stable of the wayside inn.

Religious teaching calls for obedience to its codes, homage to the Creator, and loyalty to its spiritual and material purposes in the mother-child relationship. One factor knits in a common bond all the people of the world and that is motherhood. Apart from religion 90 per cent of all civilised countries profess to some form of religious persuasion. I am not persuaded that the communist ideology can destroy in so short a time the inborn devotion of a vast people to generations of motherliness and love of babies.

Five hundred million Roman Catholics revere the Madonna and Child and all that its divinity and dignity infers and implies to congregations and individuals alike. The millions of the followers of free churches in the USA all turn to the spiritual associations of childbirth and motherhood. In England, Germany, and western European Protestant communities the helpless, demanding individuality of a baby is accepted as natural social acquisition.

Politicians have long recognised the power of women in the home, particularly in this country since they obtained the vote. In their constituencies the children and especially the babies are centres of attraction at election times. The infants of wavering constituents are photographed in public being kissed by the prospective candidate. The big cry goes up ‘Women and children first’ in hopes that the boat will not sink after all. Childbirth and its agonies swept a bill through the British Parliament and carried the House, pregnant with (political) ambition to a painless delivery from party embarrassment. Men declared it to be an effective vote catcher that no woman should be conscious of the appalling experience of childbirth. The cry was ‘anaesthesia for all’ – women, however, knew better and so did experienced midwives who deliver more than 75 per cent of women in the British Isles and soon the reports from the provinces supplied the answer. Women preferred to do without it and so did the best of midwives.

Similar uses of childbirth have been observed in other countries. It has become a focus of political propaganda which gains easy and sympathetic entrance to the homes of the people. But with what result? Vast sums of money are expended on constructions and productions for economic prestige and sometimes profit. An increasing amount is voted by a political party for general education and repairs of the nation’s stock which has not yet acquired the stamina to weather the storms of modern strains and stresses of living. But in this country a small and entirely inadequate amount of money represents the practical appreciation of the improvement of the stock of the nation. The equipment for childbirth is a disgrace to our ancient institution. When I was conducted proudly around the new Hospital Centre in Washington, DC, I did not envy but felt ashamed. Eight hundred beds cost 24 million dollars. Could not our Treasury be persuaded of the potential value of a turnout of 650,000 new lives into this small country each year? Given better equipment and teaching organisations of mothers, nurses and doctors, its quality could be improved and made competent to lead a new world to its yet undreamt-of possibilities. The standard of mind and body can be raised even before birth with our present-day knowledge. Where do politicians and industrialists look for the success of their major undertakings, in the production plants or in the repair depots? Where human beings are concerned repair depots of broken-down stock command enormous sentimental and financial support, but the production plants, which are the mothers of our nation, receive a small share only of the national purse, which must be interpreted as unpardonable ignorance and lack of foresight by those who invest for the future standard of progress of our own peoples.

The prestige of a satellite in orbit about the earth is infinitely greater than the prestige of a revolutionary approach to the breeding of better human stock, or the founding of homes and family units of happy and contented people. The uninhibited development of simple philosophy and sound physique which enables men and women to adjust themselves to an ever-changing world is allowed to occur where it may, if it will. Rockets and satellites, spaceships and hydrogen bombs absorb thousands of millions of the wealth of nations. The development of the human race to a higher standard of mental and physical efficiency is granted a niggardly and disgraceful pittance. We do not demand greater numbers – the objective must be the quality of the child. As the quality of the mother so the nature of the offspring will vary; the mother herself has been moulded by the manner of her birth and the environment in which she was influenced by her parents as a small child. The bondage or the freedom of her puberty claims the urges of her teenage years, which guide her to accept the father of her own children and so the cycle starts again in the birth of a baby. But no provision is made for this branch of education. The teenager is not taught the elementary rules of womanhood. Examinations of schools, colleges, and universities do not include in their curriculum the supremely important subject of motherhood.

Political influence cannot afford to take a long-term view. The survival of a party or a ruling combination is urgent and it must seize the vote power of today upon the promise of the immediate present. It must offer tangible rewards for loyalty to a hope and wield the power of words to support the fantasy of its invulnerability. But the potential might of man’s mind takes time to liberate, its rewards are not immediate, mutations are results of causes not the causes of results. So politically childbirth appeals to those who seek party interests. They seem to be blind to the obvious that childbirth is the entry into this society of new life, yet this incomparable responsibility is not accepted by the politicians, but handed over with grossly inadequate financial support to a branch of an uncertain and immature science to lay the foundation of our future.

Now let us see how the doctors who accept this responsibility for the standard of our stock undertake the task.

Doctors are divided into many groups and subgroups, the largest and most important of which has least influence upon the ethical trend of its organisation. These may be termed Hippocratic doctors; there are far more of them than is generally known. They work silently amongst the people, in their homes and in their hearts. They are called General Practitioners and specialise in humanity, its troubles and its weariness, its joys and successes, its well-being and its illnesses. But when the strains and stresses of survival bring rare and unusual disease, the academic specialist in that field takes charge and employs his greater knowledge and experience of the single system or function upon which he concentrates his attentions. He does not treat the person but the person’s illness or disease. There is a trend in modern medical science towards academic specialisation. It has advantages – for here lies fame and fortune and sometimes these urges militate against the Hippocratic standards of service and sacrifice; more often, however, the technical skill can restore to health and efficiency the individual and enable her to resume life at its allotted level. And there are the ‘backroom boys’ of the medical profession, working in laboratories or offices. They do not see the human being as such, but as a specimen provider for the examination that may unravel the mystery of health or disease. Finally, there are the organisers – those who have attained seats in high places. Here we may find the truly great men and women of the medical world, but in the era of pasteurisation and emulsification it is not easy to discover the cream when suspended in a medium that of itself would b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface to the First Edition

- Preface to the Fourth Edition

- Introduction

- 1 The Science of Obstetrics

- 2 Motherhood from Many Points of View

- 3 A Philosophy of Childbirth

- 4 Anatomy and Physiology

- 5 The Pain of Labour

- 6 Factors Predisposing to Low Threshold of Pain Interpretation

- 7 Fear

- 8 Imagery and the Conditioning of the Mind

- 9 The Fear of Childbirth

- 10 The Retreat of Fear

- 11 Diet in Pregnancy

- 12 The Phenomena of Labour

- 13 The Relief of Pain in Labour

- 14 Hypnosis in Childbirth as a Means of Pain Relief

- 15 The Conduct of Labour

- 16 Childbirth in Emergency

- 17 Breast-feeding and Rooming-in

- 18 The Husband and Childbirth

- 19 Antenatal Education

- 20 Preparation for Labour

- 21 Antenatal Schools of Instruction and their Organisation

- 22 In Conclusion: Thoughts Addressed to the Rising Generation of Doctors

- Appendix

- Index