![]()

ARCHITECTURES OF IRONIC COMPUTATION

HOW VIDEOGAMES OFFER NEW PROTOCOLS FOR ARCHITECTURAL EXPERIMENTATION

LUKE PEARSON

When we speak of computation in architecture today, we tend to think of it aligned to certain camps sparring for the future of the profession. This might be the promise of digital fabrication practices collapsing relationships between the design and manufacture of architecture. Or it might be the use of particle simulation and ‘deep learning’ techniques to advance ‘ultra-high resolution’ architectural materials and produce unprecedented forms. Yet much day-to-day use of computation does not engage with this ‘cutting edge’ at every turn. Social media, targeted advertising metrics and search algorithms have completely changed our everyday culture, and not always for the better. So what if we considered drawing computational approaches from other industries? The modern examples of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s maligned culture industries, perhaps?1

Videogames now surpass even the colossal commercial weight of Hollywood. But there are remarkably few architects interrogating their potential impact on architectural design and practice. This seems strange when we consider that, with the development of 3D game engines alongside the home computers, smartphones and tablets that have the power to render their scenes, creating and disseminating virtual architectural spaces has never been more prevalent. Lev Manovich once framed virtual ‘navigable spaces’ as a key innovation of ‘new media,’ yet games – which push such media forward both artistically and technologically – still seem rather under-examined.2

Minecraft (2011) is currently the go-to reference when discussing videogames and architectural creation, and understandably so given how its ‘sandbox’ system affords players considerable agency to create structures. Yet there are other examples.

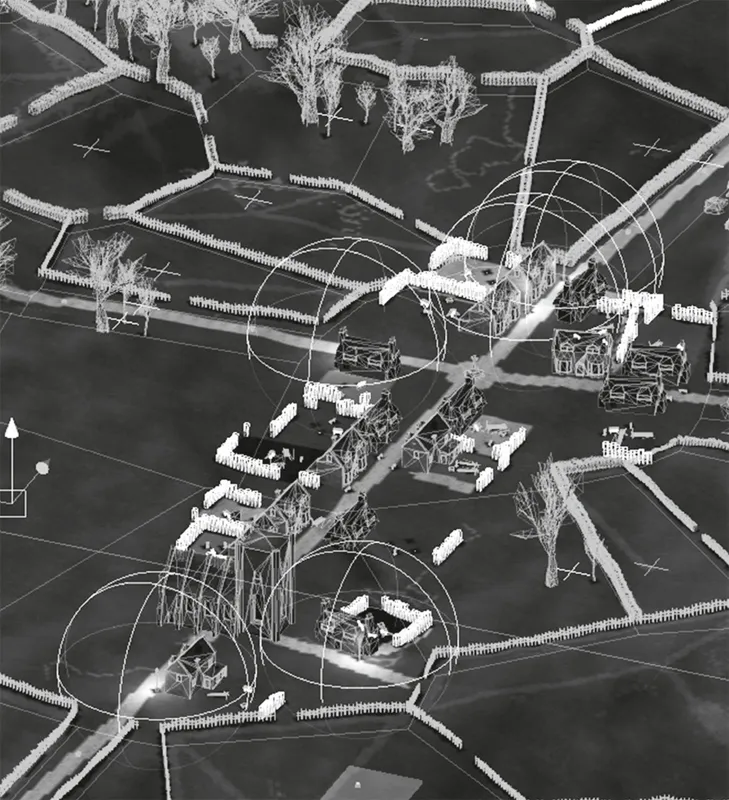

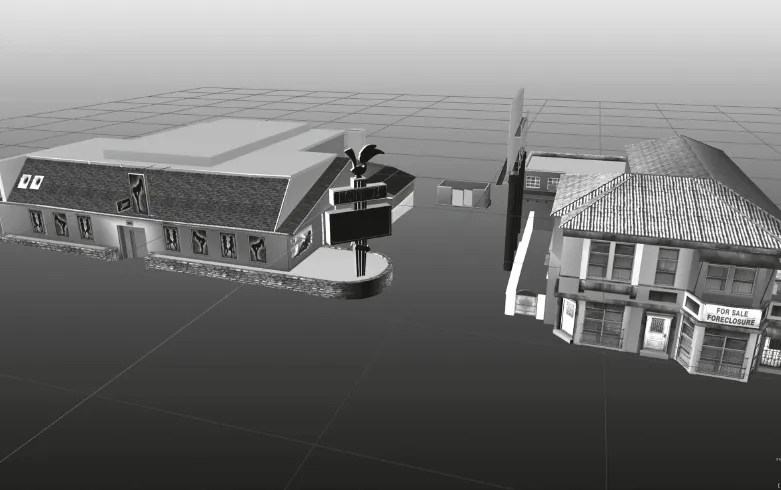

When Rockstar Games recreated Los Angeles into the metropolis of Los Santos for Grand Theft Auto V (GTA V, 2013), it was surely one of the largest projects to archive the architectural landscape of a city as part of an (estimated) US$137 million development cost. We might cite the legal relationship between the French copyright of historic structures and the facsimile of the Notre Dame in Assassin’s Creed: Unity (2014): virtual modulations of a real building required by both law of the land and ‘law of the game.’ Or we might discuss the increasingly blurred lines between game interfaces used in entertainment and those utilized in military robotics and UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles), exploiting the dexterity today’s young soldiers possess in navigating virtual spaces using a gamepad in order to regulate and control physical space.

Why then, are we not speaking about games more and welcoming them into the expanded field of architecture? Might it be that as games, they challenge a longstanding positivist relationship between architecture and technology? Or is it because of their often questionable subject matter? Or because their formal compositions privilege paradox, irony and ‘disunity’ which seem like architectural themes from another time?3 The fact that multiple discussions on the subject have identified videogames as allegorical structures (Alexander Galloway, Graeme Kirkpatrick, McKenzie Wark, and others) means that we might need to see them as media using computation for different aims and motives than those many technological evangelists of architecture promote.

Forms of Failure

In a 2015 piece for The Atlantic, videogame theorist Ian Bogost bemoaned the quasi-theocratic framing of the algorithm in contemporary culture. Bogost was concerned by how Google, Facebook or Apple ‘invite’ us into their idea of society smoothed and solved by data and the algorithm. For Bogost, such rhetoric ignores both necessary relationships to the muddle of physical reality and the fact that algorithms are representations of more complex source systems designed by people. He calls them ‘caricatures.’4 Videogames, he posits, are the only form of algorithm that publicly embraces this caricature nature. For Bogost, videogames admit what they are: rule-based representations.5 Most videogames do not have the pretension to change or save the world, but instead to uphold a temporary set of rules for one to engage with and succeed (or fail) against.

Compared to advanced manufacturing, smart cities or environmental parametrics, games might appear as folly. As Graeme Kirkpatrick states, “all video games are a kind of opening up of the machine and begin the process of prising it away from the dominant historical narrative of ‘technological progress.’”6 Of course games often do utilise cutting edge technologies in their production. Yet at the same time as big releases, smaller experimental ‘indie’ games are pulling the medium in different directions. These games all share a particular ‘videogame aesthetic.’ For Jesper Juul, the videogame is the sole artform that specifically deals with failure. As we explore the rules and limits of games, and try to succeed against them, we fail multiple times. Space within videogames becomes the location for experiments in failure: “video games are the art of failure, the singular art form that sets us up for failure and allows us to experience and experiment with failure.”7 Games provide situations and spaces within which to fail, and architectures represented within flit between supporting and mitigating failure.

Never mind the near-photorealistic ledges and precipices of an Assassin’s Creed game, Mario, the fictional character from the late 80s, would jump between platforms – two ‘built’ elements sandwiching a gap. The platforms require the gap – the zone of failure order to quantify success. These represented landscapes were first drawn on graph by designer Shigeru Miyamoto, closely resembling an architectural section.8 In Super Mario Maker (2015) such elements can now be arranged by users into novel combinations, producing levels that push at the edge of the logics of the game.

The dispersal of symbolic components creates the architectural logic of the game world. Of course, the fragmentation of symbols is not new to architectural theory. Robert Venturi, for instance, has discussed the notion of inflected elements in architecture – fragments that hint at an overall whole without explicitly disclosing it.9 As Emmanuel Petit argues, “instead of providing the literal continuity of a work’s meaning, inflection implied a formal continuity, which unfolded through time.”10 In a Mario game, architectural fragments work towards the ‘whole’ of the videogame form by supporting this relationship between progression and failure. These fragments define Mario’s landscape through inflection, emerging over the course of the game.

The architecture we experience in games is usually the facilitator of a very specific type of action enmeshed into the architectural design – whether it is trying to evoke 15th century Venice or near-future New York.

Videogames are computational media that utilise algorithms to regulate rules. But as Wark and Galloway point out – they are also allegorical. However, experiencing the ‘unique disunity’ of videogame space is not the same as reading a book about architecture or watching a film containing buildings.11 Galloway and Wark have attempted to outline the effect of games through the portmanteau allegorithm.12

This layered experience, the intuitive surface layer of the game and the underlying coded structure, work together to produce affect. As Wark states, “what is distinctive about games is that they produce for the gamer an intuitive relation to the algorithm. The intuitive experience and the organising algorithm together are an allegorithm for a future that in gamespace is forever promised but never comes to pass.”13 In this context Wark refers to ‘reality’ as gamespace.

If the allegorithm might be harnessed as a formal structure unique to games, could architects use it? Game spaces combine both contemporary coding systems and tools of architectural, photographic and cinematic representation. Architects would surely use videogames as a medium differently to commercial game designers, much as architectural flythroughs are different to feature films or soap operas.

I believe that looking towards the videogame form reveals formal techniques that I would call ironic computation. They are ironic because they deliberately and strategically sever and reassemble symbolic links through the logics of the game code, the screen, the controller and so forth. The enmeshing of ludic rules into spatial representations means videogames and their encapsulated universes might become a computational medium for thinking about architecture rather than generating it, prototyping it or manufacturing it. As Wark says, “while other media present the world as if it were for you to look at, the game engine presents worlds as if they were not just for you to look at but for you to act upon in a way that is given.”14

Enshrined in the lowbrow satirical environment of GTA V, we might find Martino Stierli’s definition of Venturi and Scott-Brown’s ‘vulgar gaze’ – an architectural elevation of unrefined culture.15 Or the infinite procedural planetary systems of No Man’s Sky (2016) might evoke Giovanni Battista Piranesi: “I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe, I would be mad enough to undertake it.”16

Towards Ironic Computation

Videogames might open new paths into digitality and its relationships to architecture. Through computation they present symbolic paradoxes to the player. The first irony of videogame structure is that good code should disappear – feats of algorithmic dexterity by developers are created in order to maintain an experience that ‘flows’ for the player. Or as Juul discusses, success against game rules might not mean narrative success.17 As Kirkpatrick suggests, gamers do not suspend disbelief of the formal contradictions of the videogame,...