![]()

1 Introduction

Catharine Patrick

Before the mid-1990s, archaeology in Birmingham did not have a high profile. Historical research (Holt 1985) had suggested that Birmingham was an important example of an industrially based medieval town but there was little in the way of excavated evidence to support this. Archaeology can provide an important and contrasting source to the traditional documentary record, even for the 18th and 19th centuries – both in terms of the evidence provided by standing buildings and in terms of the buried evidence of the lives of the urban residents. This evidence becomes progressively more important the further back in time one goes, particularly in Birmingham, where relatively few medieval documents have survived for the town.

The historic memory of the Bull Ring is not represented by buildings – these were replaced by the Bull Ring development of the ’60s and ’70s – nor is it represented by documents. The historic memory is instead represented by buried remains – yards, pits, wells, postholes, ovens, ditches and gullies – all of which can yield dating evidence and clues to the profession and status of the town’s inhabitants, and provide a glimpse of what it must have been like to live in the Bull Ring in the medieval period.

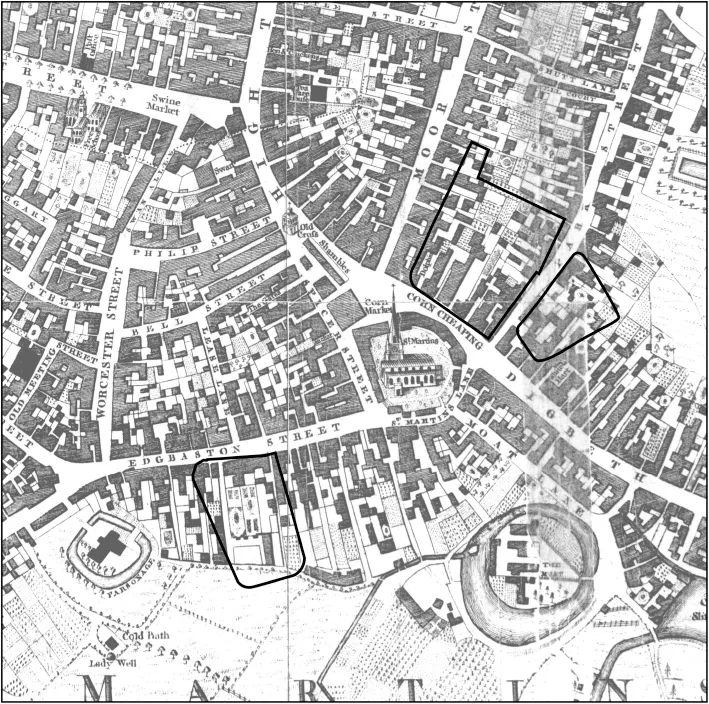

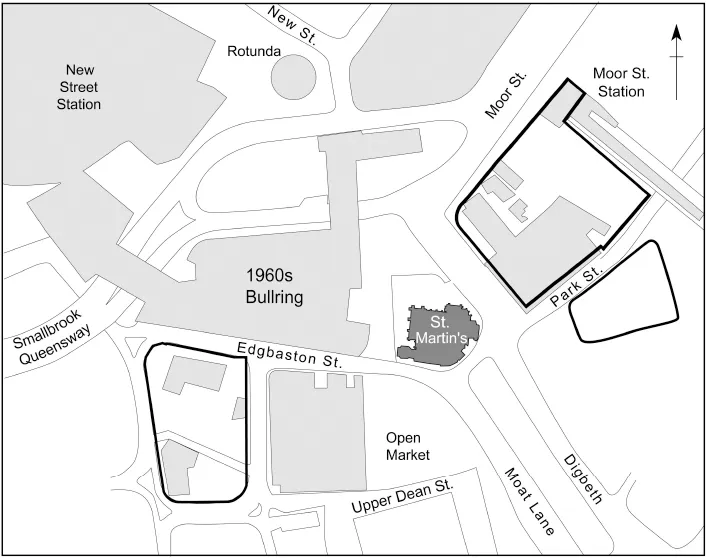

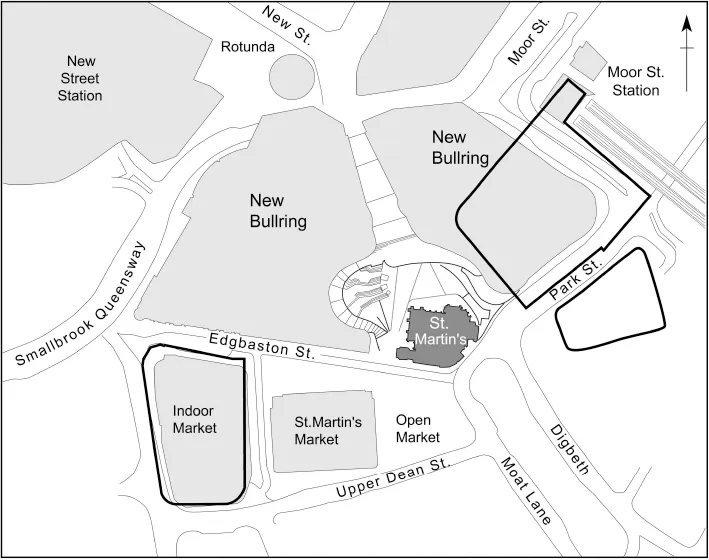

This publication focuses on archaeological sites at Edgbaston Street, Moor Street, Park Street and The Row, which are all located within the historic Bull Ring market area of Birmingham, close to the focal point of St Martin’s Church (Figs 1.1–1.4).

Geology and topography

This part of Birmingham developed on a prominent sandstone ridge about 1.2km wide. The ridge is part of the Birmingham Plateau, a geographical zone consisting of mainly Triassic rocks covered with glacial clays and gravels. The Bull Ring lies on this ridge (between 110m– 120m AOD) to the east of the conjectured Birmingham fault, overlooking a steep slope leading down via Digbeth to the lower lying and wet, marl-lined valley of the River Rea (VCH Warwickshire VII 1964).

The geology and natural topography of Birmingham are important for an understanding of the early development of the town. A good supply of water is essential to a medieval market town – it is needed for human consumption, for the watering of animals, and to drive mills, and is an essential ingredient, often in quantity, for many early crafts and industries. For early Birmingham, an important source of water was provided by springs that rose at the junction of the water-bearing Bromsgrove Sandstone Formation (formerly known as Keuper Sandstone) of the Birmingham ridge with the impervious Mercia Mudstone along the line of the Birmingham fault. These springs were the source of a number of rivulets that flowed generally southeastwards down the slope from the ridge and into the River Rea. Suitably modified and canalised, these springs and watercourses supplied the two medieval moats, Parsonage Moat and the Lord of the Manor’s (or Birmingham) Moat, which were amongst the earliest features of Birmingham’s topography. The watercourses also strongly influenced the layout of the early town. For example, the watercourse that connected Parsonage Moat with the Lord of the Manor’s Moat formed the southern boundary of the built-up area until the early 19th century (see Fig. 1.2).

Another major topographic influence on the development of the town was the rural road system which existed before the town developed. On the high ground where St Martin’s Church and the Bull Ring now stand, and where a market place was established in the 12th century, a number of local and long distance roads converged and then crossed the Rea floodplain via a single corridor, the Digbeth–Deritend–Bordesley route.

Together, the natural topography, watercourses and rural road network were important factors in shaping the development of the town. The town grew through the successive development of land parcels along the old roads and the insertion of new streets, generally roughly at right angles to the old roads, which created new land parcels for development. This street pattern then became fossilised and survived in recognisable form into the 19th century. Only with the coming of the railway, in the 19th century, and then the extraordinary road schemes and redevelopment of the 20th century, did this pattern become substantially obscured (see Figs 1.2–1.4).

Fig. 1.1 Location of Birmingham.

Moor Street and Park Street – both the focus of excavations described in this report – represent ‘insertions’ into the pre-existing road network. Edgbaston Street – the third major site described in the report – is likely to have earlier origins.

In Birmingham, as elsewhere, the typical medieval urban property plot, known as a burgage (‘town person’s’) plot, is long and thin, laid out at right angles to the street frontage. The rationale for this is simple: space on the street frontage was at a premium. The main building, perhaps a residence and/or shop, would be situated on the frontage, while the strip of land behind, the backplot, could be used for a variety of purposes – market gardening, keeping animals, industrial activities of various kinds, and waste disposal. Much of the archaeological evidence uncovered in the Bull Ring excavations relates to this sort of ‘backplot’ activity.

While the front of the plot would be defined by the road, the back end of the plot might be defined by a ditch or watercourse. Plots with a ready source of water to hand were particularly valuable. It has been noted that ‘the provision of watered plots is a recurrant feature of nascent urban settlements and, in particular, early markets’ (Baker 1995). Livestock could be grazed and watered close to the market – there would be a particular demand for such plots from the town’s butchers – while related industries such as the tanning of hides would demand a good supply of water.

Fig. 1.2 Location map showing excavated areas overlaid on 18th century map (Bradford 1750).

This pattern certainly seems to be true of early Birmingham. The plots fronting onto Edgbaston Street terminated in the watercourse connecting Parsonage Moat and the Lord of the Manor’s Moat; extensive evidence of tanning was uncovered in the archaeological excavations there. At Moor Street and Park Street, a large ditch marked the far end of the backplots fronting onto the market place and the upper end of Digbeth respectively. The ditch not only defined the original town boundary but also the edge of a deer park – Little Park or Over Park – that lay to the north and east of the early town. From the environmental evidence, a watercourse may have run along this ditch or it may simply have collected pools of standing water. Likewise, the environmental remains from a second ditch at Park Street, running at right angles to the above and defining the back end of the burgage plots running down from Park Street, indicate that it was also waterlogged. However, at Moor Street and Park Street the ditches were backfilled in the 13th century, which would seem to indicate that whatever the quantity of water they may have supplied to the burgage plots it was not considered of sufficient importance to keep them open. Park Street does seem to have had a number of water-filled ponds and tanks, which presumably provided some or all of the necessary water requirements. This is in stark contrast to Edgbaston Street, where the water-course was kept open until the late 18th or early 19th centuries. However, both the Moor Street and Park Street ditches produced plant and insect remains that provide important insights into the environment and the uses to which the ditches and adjacent land were put.

Fig. 1.3 Location map showing excavated areas in relation to the 1960s Bullring.

Background to the excavations

Edgbaston Street, Moor Street, Park Street and The Row represent part of the historic centre of Birmingham around St Martin’s Church. Research (Holt 1985; Baker 1995) suggested that evidence for the growth of Birmingham from the Middle Ages onwards was likely to be found in the immediate vicinity of the Bull Ring. The Lord of the Manor’s Moat, the smaller Parsonage Moat and their associated watercourses lie close by, and Edgbaston Street was one of the earliest streets to be laid out in the town. The notable persistence of property boundaries within the Bull Ring area suggested a high potential for the survival of archaeological deposits. It was predicted that there would be intense structural activity along the street frontages and a build-up of occupation deposits and rubbish pits within the yards and backplots to the rear. Excavation bore these suggestions out and extensive, well-preserved medieval deposits were located, generally at a depth of 1.60–3m below the present-day ground level.

The position of Moor Street and Park Street – close to the medieval and post-medieval market place – meant that archaeological deposits found there would be likely to reflect the area’s trading status. It was hoped that the archaeological evidence would help to date more precisely the insertion of the two streets into the town plan, and characterise the complexity and type of later developments.

The deposits and features identified by the archaeological investigations on all of the sites have revealed a sequence of development probably commencing soon after the granting of a market charter in the 12th century. In addition, information was gained pertaining to the economic activities which were crucial to the development of this part of Birmingham, beginning in the medieval period and continuing through the important transitional phases of the early post-medieval and later periods. The significance of industry to Birmingham in the medieval and early post-medieval periods cannot be emphasised too strongly.

The below-ground archaeology of the city centre has furthered our understanding of the chronology and form of Birmingham’s growth and has provided evidence to help to resolve vitally important questions concerning Birmingham’s early development. It has shed light on the historical development of this area from the Middle Ages up to the present day. The value of the archaeological resource in this area should not be underestimated, as Holt notes: ‘archaeology alone has the potential to offer a truly comprehensive early history of this part of Birmingham’ (Holt 1995).

Fig. 1.4 Location map showing excavated areas overlaid on modern Bullring.

Historical background

In 1086, at the time of the Domesday Book, Birmingham was only one of several small agricultural settlements within the area of the present-day city. Over the ensuing centuries this settlement evolved into a thriving trading, manufacturing and industrial town. The principal early stimulus to this development occurred in 1166 when the lord of the manor purchased a charter from the Crown allowing him to hold a weekly market and charge tolls. The charter probably legalised a pre-existing market and, as elsewhere, was no doubt obtained in an effort by the lord to create a new town around the market and enhance the value of his property through the generation of rents. Plots of building land, exclusion from tolls and privileged access to the market were offered to those who settled in the town (Holt 1985), and in the case of Birmingham this proved to be a very successful venture, signalling the rapid urbanisation of the settlement. By 1300, Birmingham and the wider region of Warwickshire had experienced a period of massive population growth and Birmingham had grown to become one of a network of market centres manufacturing and distributing goods. Lay Subsidies dating to the 1320s and 1330s show that Birmingham was the third largest town in Warwickshire after Warwick and Coventry (Holt 1985). However, Birmingham’s significance lay not in the presence of a castle (like Tamworth), nor as an administrative or religious centre (like Coventry, Shrewsbury or Stafford), but instead in its development as a trading and industrial centre for its evolving hinterland. The location of the triangular market place to the north of the manor house was probably part of this deliberate enhancement of Birmingham’s trading facilities.

The origins of Birmingham’s two moats – the Lord of the Manor’s Moat and Parsonage Moat – and their original relationship to each other are not clear but they are likely to have been important foci of rural development, and it has been suggested that they originally represented the manorial site and its ‘home farm’ (Baker 1995).

The 1166 charter refers to the market being held in the castrum and this may be the earliest surviving reference to the Lord of the Manor’s Moat. Stonework recovered during excavation of the moat (Watts 1980) has been dated to the 12th century, with parallels at Sandwell Priory, Wenlock Priory and Buildwas Abbey (pers. comm. Richard Morris). The market may have had a rival in Deritend c.1200 which, albeit temporarily, tried to capture some of Birmin...