eBook - ePub

Mary Seacole

About this book

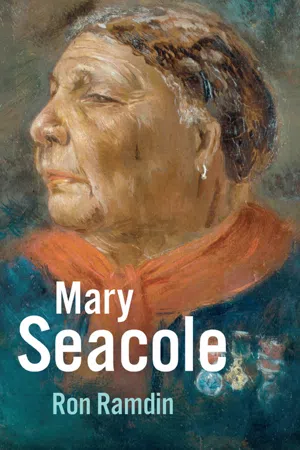

Biography of Mary Seacole, a pioneering nineteenth-century British-Jamaican nurse.

Mary Seacole's remarkable life began in Jamaica, where she was born a free person, the daughter of a black mother and white Scottish army officer. Ron Ramdin—who, like Seacole, was born in the Caribbean and emigrated to the United Kingdom—tells the remarkable story of this woman, celebrated today as a pioneering nurse.

Refused permission to serve as an army nurse, Seacole took the remarkable step of funding her own journey to the Crimean battlefront, and there, in the face of sometimes harsh opposition, she established a hotel for wounded British soldiers. Unlike Florence Nightingale—whose exploits saw her venerated as the "lady with the lamp" for generations afterward—Seacole cared for soldiers perilously close to the fighting. As Ramdin shows in this biography, Seacole's time in Crimea, for which she is best known, was only the pinnacle of a life of adventure and travel.

Mary Seacole's remarkable life began in Jamaica, where she was born a free person, the daughter of a black mother and white Scottish army officer. Ron Ramdin—who, like Seacole, was born in the Caribbean and emigrated to the United Kingdom—tells the remarkable story of this woman, celebrated today as a pioneering nurse.

Refused permission to serve as an army nurse, Seacole took the remarkable step of funding her own journey to the Crimean battlefront, and there, in the face of sometimes harsh opposition, she established a hotel for wounded British soldiers. Unlike Florence Nightingale—whose exploits saw her venerated as the "lady with the lamp" for generations afterward—Seacole cared for soldiers perilously close to the fighting. As Ramdin shows in this biography, Seacole's time in Crimea, for which she is best known, was only the pinnacle of a life of adventure and travel.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9781913368340Subtopic

World HistoryI

Early Life

Mary Seacole was born in Kingston, capital of the British island of Jamaica, in 1805. She did not give us this year herself, nor the precise day or month of her birth. She was shy of divulging such details and, in response to the question in later life, she wrote that ‘as a female and a widow, I may be well excused giving the precise date of this important event. But I do not mind confessing that the century and myself were both young together and […] we have grown side by side into age and consequence.’1

In the early 19th century, race was a major issue in Jamaica. Early researchers have commented that in order to fully understand Mary Seacole’s achievements, her work must be measured against the time in which she lived and the restrictions under which she had to operate. In 1807, two years after her birth, Britain had abolished the slave trade, but the institution of slavery persisted. When it came to civil rights in Jamaican society at this time, skin colour was all important, and throughout her childhood and for the rest of her life, Mary would have been aware of its relevance. According to Rex Nettleford, for those aspiring to become citizens, ‘the most difficult obligation of all in the scheme of preparation would have been the dilution of colour. It took three generations to become a Jamaican white by law.’2 Those wishing to gain social ascendancy were careful to choose partners ‘to ensure that offsprings would enjoy in the next generation, what Free Coloured or black mothers could not in their own.’3

Mary Seacole was the child of that class in Jamaica known as the ‘Free Coloureds’ who ‘helped to perpetuate the very basis on which the majority of the population [who were black] were denied that freedom.’4 Indeed, the free people of colour of Jamaica were placed in a paradoxical situation at this time, unlike the enslaved black people who had to fight for freedom of expression and allied rights. Although the free people of colour could express themselves through the process of free exchange – for example, petitioning – they did so on limited terms. But, importantly, they were free people in a slave society, and as such the ‘distinction had to be made between the slave and free men, despite the fact that one set of free men (Whites) made little or no distinction between another set of free men (Free Coloureds) and slaves.’5 Many free people of colour were, like white people, owners of property, including enslaved people. They believed implicitly in slaveholding and were against abolition. While many petitions were governed by law, some were embodied in customs and conventions; thus, the hierarchy of colour found expression in both, ‘giving legitimacy to carefully measured drops of white blood that flowed in the veins of Free Coloureds. The acquisition of privileges would ipso facto mean the elevation to whiteness which was in any case necessary to determine eligibility for rights and privileges – a vicious circle.’6 Whites used the ‘Free Coloured’ class as a buffer between themselves and the potentially rebellious enslaved black people. Nonetheless, this gave most free people of colour a sense of purpose despite their dis-advantages. It was through this system of special privileges that many free people of colour were able to gain access to some of society’s channels of advancement. And by reason of growing wealth, many free people of colour could travel to England and establish connections with articulate and fairly influential persons, including politicians. The trouble was that, in their fight for freedom of expression and other civil rights, free people of colour in early 19th-century Creole Jamaica failed to commit themselves to a belief in the prudence or necessity of universal privileges. As a group, at this time of slavery, the Free Coloureds seemed to have lacked anything approaching an independent ideology for freedom. They made the unpardonable error of insisting that they were eligible for freedom because they too were of white blood. Their stand was even more outrageous because the white people in their midst did not regard them as white and did all they could to ensure that any elevation to that much-coveted ethnic status would take no fewer than three generations. ‘The Creolization process was itself further distorted by the integration into the very process of the dependency syndrome, the imitative ideal,’ as Nettleford put it, ‘and the notion that what was white was right and what came from black thought much less so.’7 Thus free people of colour committed an error of judgement by adapting their quest for freedom, a game in which the rules were set by white people.

Mary’s father was a soldier and a Scotsman. While in Kingston, he stayed in a boarding house run by her mother, a free local woman of mixed black and white parents. She was, according to Jane Robinson, ‘probably a mulatto which would make Mary technically a quadroon’.8

Mary was always proud of her complexion – and the fairer one was, the greater the advantages, as we shall see later. Mary’s mother, Mrs Grant, was an admirable traditional healer of high repute amongst the officers and soldiers of both the army and navy who were stationed at Kingston and their wives. In the 1780s, the islands in the West Indies enjoyed an economic boom, during which vast fortunes were made. The chief source of this wealth was sugar, but there were other smaller valuable crops like coffee and indigo. No wonder, then, that in 1789 one-fifth of Britain’s foreign trade was with the British West Indies, and by the 1790s it had increased to one-third. By the late 1790s, the region was responsible for four-fifths of British overseas capital investments and provided over one-eighth of the government’s £31.5 million total net revenue through direct taxes and duties. Not surprisingly, to protect British vested interests, large naval and military forces were deployed to the Caribbean. With so much at stake, Britain took no chances with rivals; with a superior force at its command, Britain also colonised new territories. In such operations, Britain was more successful with the smaller islands than the larger ones. Nonetheless, the sheer scale of Britain’s presence and power was impressive. Dozens of regiments served in the West Indies. Between 1793 and 1801, ‘some 69 line infantry regiments were sent there. Another 24 followed between 1803 and 1815.’9

It was to her father that Mary attributed her ‘affection for a camp life’ and her sympathy for ‘the pomp, pride and circumstances of glorious war’.10 She seemed fascinated by war from an early age. It is clear that she was close to her father, a man of the times, a man of action and principle. She was inclined to believe that the Scottish blood in her veins was responsible for her incredibly high levels of energy and activity, which she said were not always to be found in Creoles. It was this that had impelled her towards a life characterised by variety. To her, the thought of doing one thing for too long was a dismal prospect. The term ‘lazy Creole’ was a well-known negative reference to Jamaicans (and black people generally) at the time. But this was a stereotype from which she distanced herself. She was different, very much so, and determined to prove her worth. She was unwilling to be tainted by the accusation of indolence. It is significant that early in her life she was aware of a restless energy within, an impulse that kept her on the move and never idle. It was almost second nature for her to be active. ‘I have never wanted inclination to rove,’ she wrote, ‘nor will powerful enough to find a way to carry out my wishes,’ – qualities that led her to many countries and brought her ‘into some strange and amusing adventures’.11

Mrs Grant ran a hotel called Blundell Hall, where British sailors and soldiers who were stationed in the nearby camp, Up-Park, or the military station at New-castle, met, socialised and convalesced. Soon, through keen interest and hard work, Mary’s mother gained a well-deserved reputation. Notable among her successes as a competent ‘doctress’ was the use of herbal remedies to help the victims of tropical maladies and general sick- ness.12 The death rate among British troops due to tropical disease was very high. According to one account:

[From 1793 to 1802] an estimated 45,000 British soldiers died in the West Indies, including about 1,500 officers, nearly all from fevers. In 1796 alone some 41 per cent of the white soldiers died, most of them having arrived within the past year. In the following years, efforts were made to keep white troops out of unhealthy garrisons. As a result, the mortality rate dropped to 15 per cent in 1800 and remained at about 14 per cent from 1803 to 1815. Nevertheless, about 20,000 men died from fevers, including 500 officers.13

Mrs Grant’s herbal remedies proved to be effective treatments. About the time that she was a practitioner of the herbal medical art, Thomas Dancer was convinced of the value of Jamaican local medicine and wrote in his book The Medical Assistant that ‘many of the Simples of [this] Country are endued with considerable efficacy and may be substituted for the Official ones’.14 Mary’s mother was therefore an important person in Kingston who attended to the European officers and men at her lodging house. Much earlier, in 1780, herbal medicines had been applied to cure Britain’s greatest hero of the time, Lord Nelson, of dysentery.15

Mary was not her parents’ only child. She had a brother, Edward, and a sister, Louisa. Her early life was very interesting and very unusual for a non-white child in colonial Jamaica, especially in the time of slavery. Her mother was very close and attentive to her, and naturally Mary followed, insofar as she could, in her mother’s footsteps. But in spite of this closeness between mother and daughter, there was another woman with whom she spent a good deal of time during her childhood. According to Mary, this person was an old lady who treated her as one of her own grandchildren. Nonetheless, the woman’s concern and kindness were ‘no replacement’ for Mary’s mother. But, even being aware of this, Mary recognised that she was so spoiled by the old lady that, were it not for seeing her mother and her patients as often as she did, Mary thought it very likely that she would have grown up ‘idle and useless’. Clearly she was highly valued, which boosted her self-esteem.

Not surprisingly, Mary was imbued with a sense of self, and from about the age of twelve she was spending more time at home with her mother and would assist with household duties. Often, she would confide in her mother ‘the ambition to become a doctress’ which ‘took firm root in my mind’. She admitted to being very young and lacking knowledge, but what little she had was gained by observing her mother. The propensity for children to play-act (and Mary was no exception) led her to relate how readily she imposed her ‘childish griefs and blandishments’ upon a doll. Quick learner that she was, Mary made ‘good use’ of her ‘dumb companion and confidante’. Thus, her doll was susceptible to every disease that affected the local people, and her fertile, growing mind imagined medical triumphs that resulted in saving a few ‘valuable lives’. None of these simulations, however, were as gratifying as fancying the ‘glow of health’ returning to the doll’s face after long and life-threatening illnesses. As ambition got the better of Mary, she was sufficiently in the habit of empathy and sympathy to extend her practice to ‘dogs and cats’ to whom she transferred their owners’ diseases. In turn, she would administer the likely remedies she deemed suitable for the complaints. In time, her ministrations grew more ambitious, and in the absence of human patients she would play out the patient/nurse roles herself.16

The sea was always close by as Mary grew up. Kingston Harbour was crowded with ships of various shapes and sizes. And, having been lively and ambitious from an early age, Mary was smitten by a longing to travel. Her imagination ranged freely as she traced her finger over an old map, moving it along and up from island to island in the Caribbean Sea and then across the Atlantic from Jamaica to England. She was fond of the ‘stately ships’ in Kingston Harbour, many of them bound for England. Soon her improbable, girlish longing was realised, for, as she put it, ‘circumstances, which I need not explain, enabled me to accompany some relatives to England while I was yet a very young woman.’17 How young? A relatively recent biography dates this first visit to England to 1822, when Mary was about nineteen years old.18 Once again, this raises interesting questions. For example, who were her ‘relatives’? Mary wrote that her companion was ‘very dark’, but it is worth speculating whether a white person was also travelling with them. Slavery was the defining factor in colonial life at this time. Yet Mary mentions little or nothing about it in Jamaica, and from the tone of her writing, in retrospect, she seemed little bothered or affected by that ‘peculiar institution’. She was eager, though, to expand on her first impressions of the great metropolis, London. It is significant that she came into contact with street boys who made fun of her colour. In England this was especially interesting to Mary, who was like an island – a conspicu-ous minority surrounded by a sea of white. She became acutely self-conscious. Her skin was different, even though it was ‘only a little brown’, which she regarded as nearly white.19

In the 1820s, there were many black people in and around Central London, although the black population had dwindled to an estimated 10,000 from 15,000 in the 1780s.20 The anti-slavery movement and parliamentary reform were key issues in London. Thus far in her life, references to Mary’s complexion may have mattered much less than they did now that she was surrounded by the white multitudes of London. If it had not happened before, it was here and now that an awareness of her skin colour would burn itself into her consciousness. For now, the street boys reminded her at every turn of this aspect of her presence. But although Mary writes little or nothing about the matter, it would be very surprising if she did not encounter people in London who were much darker in complexion than she was. Generations of black people had lived there, and now the evidence was to be seen in their descendants. Indeed, around this time, the young and soon-to-be-famous black Chartist William Cuffay was playing his part in the Chartist campaign for economic and social justice. Years later, at the time of the delivery of the People’s Charter to Parliament, he was charged, convicted and transported to Tasmania, where he spent the rest of his days in a workhouse.21 So parliamentary reform, Chartism and anti-slavery were issues that all contributed to a raised awareness of the question of race and freedom among people whose skin was of a darker hue. On these issues Mary remained silent, but to the matter of her race she would return again some years later:

I am only a little brown – a few shades duskier than the brunettes whom you all admire so much; but my companion was very dark, and a fair (if I can apply the term to her) subject for their rude wit. She was hottempered, poor thing! And as there were no policemen to awe the boys and turn our servants’ head in those days, our progress through the London streets was sometimes a rather chequered one.22

We do not know where Mary stayed for the year she spent in England before returning to Kingston. But soon she was on her way back, making her second trip to London. This visit was, for the curious young woman, an eye-opener. But why did she return so quickly ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Frontmatter

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- 1. Early Life

- 2. Business and Nursing

- 3. Determined to Serve

- 4. Onward, At Last

- 5. Prelude to War

- 6. The British Hotel

- 7. Amidst the Carnage

- 8. Aftermath

- 9. Last Years: Crimean Heroine

- Notes

- Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mary Seacole by Ron Ramdin in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.