- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

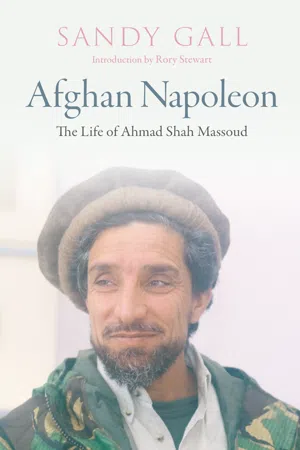

The first biography in a decade of Afghan resistance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud.

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the forces of resistance were disparate. Many groups were caught up in fighting each other and competing for Western arms. The exception were those commanded by Ahmad Shah Massoud, the military strategist and political operator who solidified the resistance and undermined the Russian occupation, leading resistance members to a series of defensive victories.

Sandy Gall followed Massoud during Soviet incursions and reported on the war in Afghanistan, and he draws on this first-hand experience in his biography of this charismatic guerrilla commander. Afghan Napoleon includes excerpts from the surviving volumes of Massoud's prolific diaries—many translated into English for the first time—which detail crucial moments in his personal life and during his time in the resistance. Born into a liberalizing Afghanistan in the 1960s, Massoud ardently opposed communism, and he rose to prominence by coordinating the defense of the Panjsher Valley against Soviet offensives. Despite being under-equipped and outnumbered, he orchestrated a series of victories over the Russians. Massoud's assassination in 2001, just two days before the attack on the Twin Towers, is believed to have been ordered by Osama bin Laden. Despite the ultimate frustration of Massoud's attempts to build political consensus, he is recognized today as a national hero.

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the forces of resistance were disparate. Many groups were caught up in fighting each other and competing for Western arms. The exception were those commanded by Ahmad Shah Massoud, the military strategist and political operator who solidified the resistance and undermined the Russian occupation, leading resistance members to a series of defensive victories.

Sandy Gall followed Massoud during Soviet incursions and reported on the war in Afghanistan, and he draws on this first-hand experience in his biography of this charismatic guerrilla commander. Afghan Napoleon includes excerpts from the surviving volumes of Massoud's prolific diaries—many translated into English for the first time—which detail crucial moments in his personal life and during his time in the resistance. Born into a liberalizing Afghanistan in the 1960s, Massoud ardently opposed communism, and he rose to prominence by coordinating the defense of the Panjsher Valley against Soviet offensives. Despite being under-equipped and outnumbered, he orchestrated a series of victories over the Russians. Massoud's assassination in 2001, just two days before the attack on the Twin Towers, is believed to have been ordered by Osama bin Laden. Despite the ultimate frustration of Massoud's attempts to build political consensus, he is recognized today as a national hero.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Afghan Napoleon by Sandy Gall in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781913368234Subtopic

Historical Biographies1

The British ‘Find’ Massoud

Christmas 1979 was memorable for all the wrong sorts of reasons, at least for the leaders of the United States and Great Britain in particular. While Margaret Thatcher, the British prime minister, her United States counterpart, President Jimmy Carter, and their respective families were preparing to celebrate a convivial Christmas – one at Chequers, near London, and the other at Camp David in the Appalachian Mountains near Washington – the Politburo in Moscow was putting the finishing touches to its top-secret plans to invade Afghanistan and remove from power the brutal and erratic communist prime minister, Hafizullah Amin. Moscow had been debating whether and how to get rid of the increasingly unpopular Amin for several weeks, and any doubts it may have had were dispelled by news from Kabul that he had just had the president, Nur Mohammad Taraki, murdered – suffocated by his own guards.1

The Soviet president, Leonid Brezhnev, was especially angry, having promised to protect Taraki. ‘What a bastard, that Amin, to murder the man with whom he made the revolution,’ he told his colleagues in the Kremlin.2 KGB head Yuri Andropov, ‘mortified’ by his department’s failure to keep control of events, was equally determined to get rid of Amin and install a more manageable leader. With its influence in Kabul now almost zero, and popular unrest in Afghanistan growing, the Soviet leadership turned increasingly to the idea of using force. In fact, Amin had appealed repeatedly to the Kremlin to send troops to Afghanistan to help him keep control of the country. Brezhnev had always refused. Now he saw the request as a perfect opportunity.

The crucial meeting of the Politburo took place on 12 December. Andropov claimed that Amin was increasingly in contact with the CIA – he had studied in America – and warned that if he were to shift his foreign policy towards the West, it could have serious implications for the Soviet Union. Finally, the meeting decided unanimously to send in the troops.3 Amin seemed to be oblivious to what was coming.

The Russians invaded on 25 December, Christmas Day, stormed Amin’s palace, and killed him. The invasion came as a shock to the leaders of the West, particularly to President Carter, who, despite having seen satellite images of the Soviet military build-up, which the CIA provided in abundance, apparently did not believe the Russians would actually take the plunge. On 28 December, he rang Thatcher. ‘We discussed at length what the Soviets were doing in Afghanistan,’ she wrote in her memoirs, ‘and what our reaction should be. What had happened was a bitter blow to him.’4 She was less surprised than Carter, being more sceptical of Russian intentions. ‘From now on,’ she added, ‘the whole tone of international affairs began to change, and for the better. Hard-headed realism and strong defence became the order of the day. The Soviets had made a fatal miscalculation: they had prepared the way for the renaissance of America under Ronald Reagan.’

Soon after the invasion, Gerry Warner,5 the newly appointed Far East controller of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, better known as MI6), was briefing one of his brightest young officers about a mission which was a direct result of the Soviet invasion, and about the long conversation between Thatcher and Carter. During that conversation, they had jointly agreed they would give the Afghans all the help they could against the Russians – short of going to war. Warner’s briefing concluded with what has become a famously worded assignment: ‘I want you to go and find Napoleon when he is still an artillery officer.’6

‘Why Napoleon?’ I asked Warner later.

‘Because he was a colonel of artillery who became Emperor of France,’ he replied. ‘That was the sort of person we were looking for.’7

And they found him, as we shall see.

So, the ‘very, very able and intelligent chap’, as Warner described his emissary, an ex-soldier in receipt of what might have been considered a very tall order, packed his bags and set out soon afterwards for Islamabad, the garden-city capital of Pakistan, designed by Greek architects, where MI6 had an office in the British High Commission (as the embassy is known, since Pakistan is part of the British Commonwealth). After listening to the advice of his colleagues there, he drove up the Grand Trunk Road – a relic of the days of the Raj – to Peshawar, the capital of what was still known as the North-West Frontier Province (and is now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province), the stepping stone to the Khyber Pass and Afghanistan.

Peshawar was the sort of place where, not very far from the old- fashioned, down-at-heel, very British Dean’s Hotel, he might have seen – as I did one day – Afghan horsemen in turbans trotting across a bridge into the main bazaar. They made me think of Kipling, his love affair with the tribal culture of the frontier, and that great epic poem, ‘The Ballad of East and West’.

Peshawar was also the centre of the fledgling Afghan resistance movement. This was the place to put your ear to the ground. This ‘our chap’ did, ending up with a name which would become world famous: Ahmad Shah Massoud, a dynamic young Afghan mujahideen8 commander who was already making a name for himself fighting the Russians. The word ‘massoud’ – also spelled ‘masood’ or ‘masud’ – means ‘lucky’ in Persian; Commander Massoud, as he became, was to be almost unbelievably lucky until one day, in September 2001, his luck ran out. But that was still a long way away in the future.

The MI6 officer from London returned in due course and reported back to his superiors. ‘We realised three things,’ Warner said. ‘First of all, the Americans and the Pakistanis were in complete control of all the people in the south of Afghanistan, who on the whole were more extreme Muslims – Islamists.’9 He was referring to the warlike Pashtun clans, such as the Haqqanis, who lived mainly in the south of Afghanistan, made up about 40 per cent of the population, and were also a substantial minority in Pakistan. There are about five million Pashtuns in Afghanistan and ten million in Pakistan, a consequence of the redrawing in 1893 of the Afghan–Indian (now Afghan–Pakistani) border, known as the Durand Line, by the British civil servant Henry Durand and the Afghan ruler Amir Abdur Rahman.

The second thing, Warner said, was that ‘the CIA were very sensibly banned from going into Afghanistan themselves, because any direct conflict between the superpowers, in the shape of the CIA and the KGB, might well have had serious repercussions. The third thing and the most important, really, was that we had heard of this chap up in the Panjsher’ – Ahmad Shah Massoud. Unlike the CIA, MI6 did not have a blanket ban on entering Afghanistan but, ‘as with all our operations, we sought political clearance on each individual operation. The CIA could not get to Massoud in the Panjsher. We could, and by so doing could make an important and distinctive contribution to the overall support of the mujahideen.’10

But first, the MI6 officer sent to Pakistan to find an ‘Afghan Napoleon’ had to be sure he had the right man. To gauge how the war was going, the British tracked Russian internal communications through their secret listening station, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), presumably picking up accounts of battles. ‘This man stuck out to me as somebody who was prepared to do things and get on with it and so – I suppose you could say – I selected him,’ the MI6 officer said. The aim was ‘to make things as bloody difficult for the Soviets as we could and support what we thought was the right sort of person to do it.’11 The British noted that Massoud had established territorial control of the Panjsher Valley, pushed government troops out of much of the valley, and occasionally sent units to hit Russian forces beyond. Warner agreed with his emissary: ‘Massoud’s quality impressed the first people who met him straightaway,’ and he noted that Massoud, for his part, was ‘quick to realise that this was an opportunity’ and that ‘the sort of help we were prepared to offer was in fact very worthwhile.’

With what seem higher moral principles than were often displayed in the Cold War, Warner decided to cross the border into Afghanistan to satisfy himself that the Afghans ‘knew what they were getting into’. A small jirga, a tribal assembly, was arranged in a school, presumably in the border area – he could not remember where:

Maybe half a hundred Afghans [including] three or four with long white beards, sat in a dusty schoolyard. I said I had come because I wanted to tell them that if they wished [to have] our help we were prepared to give it, but I wanted to be sure they understood that, if we did give them our help, they would be able to fight longer, but that would mean that more of their young men would be killed. And I did not believe they would be able to beat the Soviets, or that the Soviets would leave.

This was early 1980. So, there was a bit of muttering, and the oldest and wisest of the group said: ‘Please tell this gentleman that we will be grateful for his help, but we are not asking for it. If he wishes to give it to us, that is fine, and you may also tell him that the Russkis, the Soviets, will leave Afghanistan within ten years.’

Not that bad, since they left in nine! But I wanted to make quite sure that I was not doing an ‘America in Vietnam’ and encouraging people to fight who didn’t want to fight. So, our consciences, as far as that was concerned, were clear. And then of course it was what our chap would have said to Massoud when he went to the Panjsher.12

Then, having decided Massoud was their man:

[MI6 decided] what we were going to do, and how we were going to sell this to everybody else, and worked out a plan, which was really to go and find out from him what he needed and what help we could give. We put this proposal to the foreign secretary, Lord Carrington, and Mrs Thatcher. They approved, with the caveat that we should not offer to provide arms.13

MI6’s next step, with the Foreign Office’s approval, was to send in a small team to meet Massoud. ‘It went really well, and subsequently we gave Massoud really important help – communications, short-range wireless and some long-range wireless. We never gave him any lethal equipment. We did bring out some of his leading people for training, both in a Gulf country and in Britain.’14 Some of this training took place in country houses with cooperative and discreet owners. In other cases, the trainees were housed in old army camps.

The British realised they could not make the kind of contribution in financial terms the Americans were already making, Warner said, ‘but we could make a difference with somebody who was isolated, out on his own, far away, and whom we thought we could help.’ As the junior partner, MI6 had to coordinate with the CIA, which was already deeply involved in supporting the Afghan mujahideen and had the money. Ironically, while the CIA – which was heavily influenced by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI) – always had reservations about Massoud, the Russians, including some very senior officers like General Valentin Varennikov, a veteran of Stalingrad, saw him as a cult figure. General Ter-Grigoryants, who fought against Massoud, also called him ‘a very worthy opponent and a highly competent organiser of military operations’:

His opportunities for securing weapons and ammunition were extremely limited, and his equipment was distinctly inferior to that of the Soviet and [Afghan] government forces. But he was nevertheless able to organise the defence of the Panjsher in a way which made it very difficult for us to break through and to take control of the valley.15

Despite American reservations about Massoud, however, the MI6 officer who ‘found’ Massoud went to Washington and argued the case for him, he said, with a well-known CIA chief: ‘They eventually said, “OK. We’ll give you what you want, and we’ll support you on this, and you’ll have this as your territory, and we’ll do our own thing.” And, as we know, they went after [Gulbuddin] Hekmatyar, God bless them, etc.’16 He smiled.

2

Were We Nearly Shot?: Meeting Massoud

In the summer of 1982, three television colleagues and I trekked for twelve days with a mujahideen arms convoy over the mountains and across the scorchingly hot plains of Afghanistan in search of the young Massoud, already known for his role in the resistance struggle against the Russians. To reach his stronghold in the Panjsher Valley, north-east of Kabul, we walked about 150 miles from the border through a largely deserted landscape, most of the inhabitants having fled as refugees to neighbouring Pakistan. It was the third year of the bitter war between the mainly conscripted 80,000-strong Russian 40th Army and the Afghan mujahideen – literally ‘holy warriors’ – who were said to be fighting the Russians as bravely and determinedly as their forefathers had fought the British in three wars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

For much of the time, as my small television team and I toiled over mountain passes and waded across fast-running rivers, we were shadowed by Soviet reconnaissance Antonov aircraft buzzing like hornets overhead. Never very far away were rocket-armed Mi-24 ‘Crocodile’ helicopter gun-ships, instantly recognisable by the menacing beat of their rotors, and the latest Soviet jets – Sukhoi Su-27 fighter-bombers, NATO code name ‘Frogfoot’, which came at you faster than the speed of sound to drop their deadly cargo with a devastating roar.

Were they really tracking us in particular, or merely keeping an eye on just another mujahideen convoy moving through the mountains? Probably the latter, although if they had realised the convoy was intended for Massoud, whom they considered public enemy number one, it would probably have become a priority target. Yet we were bombed only once or twice on the way in, rather desultorily, causing little damage. But later – once we were in the valley and the Russian offensive known as Panjsher VI had started – it was a different story: the bombing became frequent, heavy, and, on several occasions, alarmingly close.

We had started out from Peshawar, crossing the border at a village called Terri-Mangal – named after the two tribes who lived there – and walked north through the empty villages of Ningrahar Province, their inhabitants driven out by Soviet bombing and ground attacks. Only a few old men had stayed on to look after their property, mainly livestock and houses. In the two and a half years since the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, between four and five million Afghans – men, women, and children – had fled their homes,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Introduction

- Author’s Note

- Translator’s Note

- Prologue

- 1. The British ‘Find’ Massoud

- 2. Were We Nearly Shot?: Meeting Massoud

- 3. The Boy Who Loved Playing Soldiers

- 4. The Coup that Failed: Exile in Pakistan

- 5. Bombed by the Russians in the Panjsher

- 6. The Russians Propose a Ceasefire

- 7. Massoud Deals with the Russians

- 8. Marriage and War

- 9. Defeat and Failure: ‘Am I Afraid of Death?’

- 10. The Russian Perspective

- 11. A Winter Offensive

- 12. Massoud Takes Farkhar

- 13. Expanding into the North

- 14. The Russians Prepare to Withdraw

- 15. Massoud Captures Kabul

- 16. Under Siege: Massoud in Kabul

- 17. Tea and Rockets with the Taliban

- 18. Mortal Enemies

- 19. Massoud Retreats from Kabul

- 20. A Low Ebb

- 21. ‘My Father was Incorruptible’

- 22. Massoud Visits Europe

- 23. How They Killed Massoud

- 24. The Eve of Assassination

- 25. A Final Encounter

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgements

- Select Bibliography

- Notes

- Index