![]()

1 Erotic Images, Pornography,

Shunga and their Use

The encounter of foreign countries with Japanese erotica began a surprisingly long time ago. In 1615, shock was registered in London when the first imported Japanese ‘lasciuious bookes and pictures’ were briefly seen before being summarily burned.1 At about the same time, moralists of the Ming dynasty in China were counselling against the ‘extremely detestable custom’ of importing Japanese ‘spring pictures’, which led to lewdness.2 Korean ambassadors were regular visitors to Japan, and thought the deplorable condition of sexual ethics, which they believed they saw there, must surely have been the result of unfettered circulation of the wrong sort of picture.3

Few works are left from these early periods, and accordingly this book will address primarily those of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. But there are good reasons apart from the fortuity of survival for doing this. The growth of printing vastly expanded the output of all kinds of picture and text from the 1680s, and massive urbanization concentrated and expanded readership for many works. But cities were demographically artificial, and none more so than the shogunal capital of Edo (modern Tokyo), also the centre of printing, which may have been two-thirds male. This had clear implications for auto-eroticism and hence erotica. Many men lived in the large garrisons serving the Edo palaces of the 280 or so regional princes (daimyo) who governed the Japanese states, and their barrack quarters deprived them of access to females. The late seventeenth-century fictionalist Ihara Saikaku referred to Edo as the ‘city of bachelors’.4 Even those of non-military caste were often living without family roots and traditional networks of socialization and fraternization.

With roughly one million inhabitants, few of whom had been born there, Edo became a centre for the generation of disenfranchised urban modes. But it was not a place of laxity and freedom, sexual or other. The city was disciplined and under tight control. Pictures showed the city as it was not, or rather, they showed its illusory spaces of pleasure and momentary enjoyment, adrift from normalcy: that is, they showed the ‘Floating World’ (ukiyo). The shogun’s chief minister at the turn of the eighteenth century expressed horror that future generations might look back at these vain and eroticized images and conclude that such was how Edo had really been. He did not seek to ban all libidinous pictures, but, as we shall see in chapter Two, he did relegate them back to their proper spheres; some artists were punished. All art contests the real, but, with erotica, we are dealing with a sort that sets out, as its objective, to misrepresent. Unlike all other genres, erotica – shunga, pornography or whatever – triggers a viewer into willing deceptions which the body’s physiology, aided most often by hands and fingers, takes further in summoning up fantasies of pleasure.

THE LIBIDINOUS IMAGE

Although I wish to erode the too-easy division made between erotica as such and ‘normal’ pictures of the Floating World, it is nevertheless important to establish some terms. The usual designations for the former were the descriptive ‘pillow pictures’ (makura-e) and the euphemistic ‘laughing pictures’ (warai-e); the second sounds less coy when we realize that ‘laughter’ also meant masturbation. Another term was ‘sexual book’ (kōshokubon), which tends to figure in official pronouncements, and a vernacular term with the same meaning (ehon). Also known was the blunt ‘dangerous pictures’ (abunae). Here is the crux: these items were for a purpose that people found hard to talk about, and this naturally clouds the issue. I use these terms where necessary but have preferred to harmonize them under the label ‘shunga’. Although already known in the nineteenth century, shunga is the word deployed today to create a distance from the subject. It is neither antiquarian, nor does it condone a readership seeking to rekindle the original purposes of publication in their own bedrooms today. Since I am seeking to delineate a field for erotic images beyond the overtly sexual, I find shunga the best term to use. The English ‘pornography’ will do as well, although it may carry baggage that is not entirely helpful.

Until recently, it was illegal under Japanese law to publish images of human genitals, pubic hair or anuses (interestingly, though, semen could be shown). The law applied to modern and historic works, which in a way was heartening since it at least showed the authorities were taking the subject-matter at face value and were not ready to consign pictures to the meaningless void of ‘art’ just because they were old. An absolute continuum was assumed between what a modern reader would end up doing with historical and with modern pornography. It was fraudulent, however, that this policy was pursued while promoting non-overt equivalents as if they had no connection with the libido and with auto-eroticism. The male and female prostitutes and blatant sex symbols that feature in so many ‘normal’ pictures of the Floating World were deemed to count for nothing. The great divide between the two was thoroughly artificial.

Cut off from their larger sustaining pool, and reproduce-able only with such egregious bowdlerizations as to make them worthless for art-historical as well as onanistic purposes, shunga retained a wraithlike existence as supports to sexo-logical writings on the Edo period, much of which was fine, but little of which regarded pictures as important in their own right, much less as having any claim to being a discrete semiotic system. On the other hand, the few people outside Japan who investigated the matter beat the censorship laws obtaining there with the stick of overstatements about the acceptability of shunga in their original context. We may be sure that Edo parents, spouses and officials were worried about the availability of shunga and (a crucial point) about the pull of the whole panoply of Floating World culture.

The law has recently changed, provoking a surge of reissuings of and commentaries on shunga, some of it undertaken by prominent art historians. Much material has come to light, most of it, notably, by artists already respected for their achievements in ‘normal’ Floating World imagery. The choicer pieces of shunga have acceded to the embrace of ‘Japanese art’. This has brought a rather different problem. While we do now have a better idea of how high shunga can climb aesthetically, and how oeuvres fit together and developments occur, the art historians have ousted the sexologists, and with a few laudable exceptions the issue of use has fallen further into the abyss. Most art historians are unwilling to make statements about the history of sexuality, and in any case they seldom concern themselves with use at all, and when that use is masturbation, they wish to proffer nothing. Shunga have become ‘art’ and their context has contracted to that which academe allows for artistic genres, namely position in the oeuvre, biography of the maker, developmental position in the type, etc. I have benefited from recent work but insist that shunga belong within a configuration of libidinous images that ripple outwards with no clear demarcation line. Shunga are bound to a context that subsumes the histories of pictures and of sexual behaviour. Only by treating them in this way can we see them for what they are: libidinous representation. It is now commonplace to call the fantasies fostered by erotica ‘pornotopia’.5 No one has so far attempted to identify a ‘shungatopia’, or the false salaciousness of images that substituted for experience in the Edo world.

SHUNGA AND ‘PICTURES OF BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE’

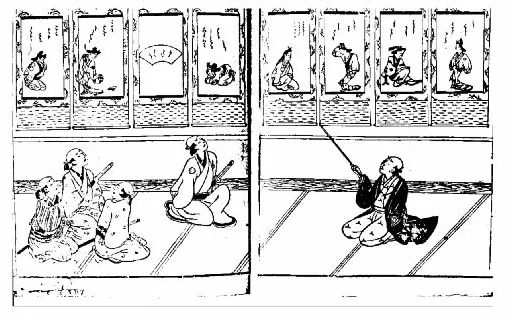

At the forefront of themes depicted by ‘normal’ artists of the Floating World was a genre with no parallel in Western art: ‘pictures of beautiful people’ (bijin-ga). There were numerous subdivisions. In the Edo language, both genders were covered, although with the characteristic twist of the compulsory heterosexuality that emerged in Japan in the late nineteenth century, the label is now used to refer only to pictures of beautiful women. Worse, it seems, than masturbation over pictures of females is that over pictures of males (the gender of the masturbator is a question that will be addressed below). ‘Pictures of beautiful people’ do not show the sexual act, which has enabled them to be cleansed and displayed unproblematically. But in most cases the sitters were people whose sexual persona defined them, and so sex defines the picture too. Ihara Saikaku included a story in his Great Mirror of Sexual Matters (Shoen ōkagami) of 1684 of a court minister forced to relocate in the desolate provinces, who took such pictures, referred to as ‘likenesses of courtesans’ (taiyū no sugata-e), to appease himself. As Saikaku’s book was illustrated, the reader is given a rendition of the man, pictures hanging up (seven portraits and one piece of calligraphy on a fan), with four admirers who have befriended him and come to view them (illus. 1).

2 Anon., Monk Worshipping a Painting, monochrome woodblock illustration for Kōshoku tabi nikki (1687).

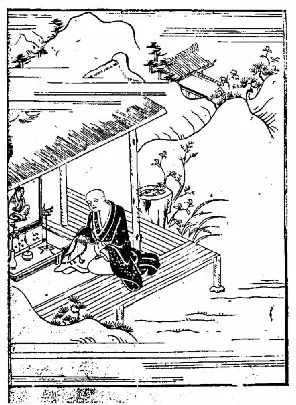

1 Anon., The Minister Relocated to the Northern Provinces, monochrome woodblock illustration for Ihara Saikaku, Shoen ōkagami (Kōshoku nidai otoko) (1684).

On seeing the set of eight scrolls, their emotions overflowed and their words, they found, were unequal. The minister and his four companions each approached close, worshipping the images. They could not get enough of recitations of poetry and extollings of the wondrous delineations of the women’s likenesses. The friends begged to be told, for their delight, how the minister had done the ‘fine thing’ with these women long ago, and asked to hear more and more about what they had been like, since just looking could never suffice.6

The term ‘worship’ (ogamu) is used to describe their activity before the paintings. There are other anecdotes of ‘worshipping’ ‘beautiful-people’ pictures. The anonymous Sexual Travel Diary (Kōshoku tabi nikki) of 1687, for example, tells of a sybarite who travelled in search of erotic encounters before ultimately retiring to a life of solitude as a monk. He left the company of beautiful men and women (both of which he had enjoyed) but could not forego sex altogether, and so took a picture of his favourite partner, treating it as a devotional icon (honzon) and ‘worshipping it, trusting in its efficacy’ (illus. 2).7 A third, similar story is of a man who commissions ‘Hishikawa’ (that is, the great commoner artist Moronobu) to do the image of youths for him to ‘worship’, and this he is said to do all through the night.8 These sound like covert references to a quite different activity. Since the anonymously authored book is entitled Male and Female Prostitutes Play the Shamisen Together (Yakei tomo-jamisen), the shamisen being an instrument associated with the pleasure quarters, the kind of liaison the man hopes for with the boys is transparent. In the centre he hangs his favourite, with the two others flanking, in the manner of a sacred triad, where lower divinities stand beside a Buddha. The man had these ‘always suspended in the place where he slept’, and...