![]()

INTERLUDE 1

BETTYMANIA

One of my favorite archival finds from the Folger Shakespeare Library is a book of paper dolls published in 1811. Titled “Young Albert, The Roscius, Exhibited in a Series of Characters from Shakespeare and other Authors,” this second edition booklet includes seven pages of colored illustrations depicting such characters as Falstaff, Hamlet, Othello, Young Norval, and Richard III, each with an opening for one of “Young Albert’s” (white or black) heads. On the facing pages, short excerpts offer clues to the dramatic moments the dolls are meant to inhabit. As a uniquely scriptive thing, the booklet invites those who encounter it to quite literally play with Albert’s repertoire, to familiarize themselves with the gestures, costumes, settings, and narratives that defined each role, to imagine crossing borders of gender, age, race, class, and genre, and to delight in the fluidity of performance and the vantage points of the characters’ heroic lives.1

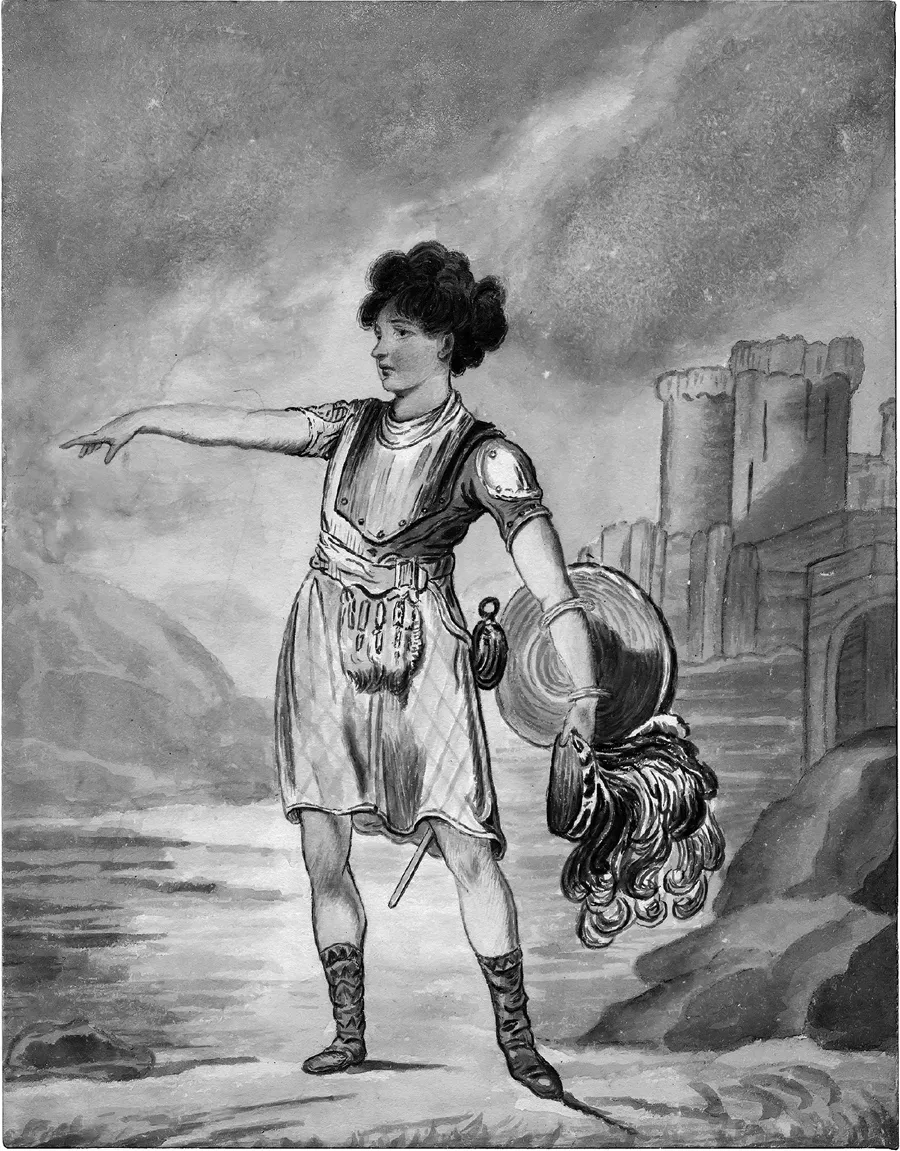

“Young Albert” is almost certainly modeled on the real-life Master William Henry West Betty (Master Betty for short), the twelve-year-old “Infant Roscius” who captivated London audiences in the 1804–1805 season. Betty’s repertoire included Young Norval in Douglas, Romeo in Romeo and Juliet, Achmet in Barbarossa, and the title role in Hamlet. As one of the first child celebrities of the modern era, he circulated within an evolving economy of cuteness wherein he was valued for his size, charm, and vulnerability, especially when he was ill or indisposed. Audiences admired Betty’s physical appearance and collected biographical pamphlets, caricatures, and souvenirs bearing his likeness. Such objects, including the booklet of paper dolls, contributed to the production of a nascent celebrity culture, mediating the relationship between Betty and his audience. The development of Betty’s distinctly masculine repertoire and the mania that surrounded him offstage is the focus of this short interlude.

Born in Shrewsbury in 1791, Betty made his stunning debut in Belfast in August 1803, several weeks shy of his twelfth birthday, playing the role of Osman in Aaron Hill’s Zara, one of the era’s most iconic Romantic heroes. But it was a very different Romantic model that had first drawn Betty to the stage. According to his biographers, Betty fell in love with acting after attending a production of Pizarro (1799), Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s tragedy about the Spanish conquest of Peru starring the celebrated actress Sarah Siddons in the role of Elvira, the title character’s Spanish mistress. Siddons’s performance, which enhanced the character’s “mixed dignity and tenderness” and the “virtuous struggles of repentance and remorse,”2 so entranced young Betty that when he returned home “his conversation ran upon the character of Elvira and the fascinations of the drama.”3 He set about learning all of Elvira’s emotional speeches “in imitation of Mrs. Siddons,” which he then recited to his parents and their friends.4 I linger on the events of Betty’s first theatre outing to emphasize how his passion for acting arose through cross-gender identification, his fascination with both Siddons and the character of Elvira. Ultimately, Betty’s parents gave in to their son’s pleas and hired Mr. Hough, the Belfast Theatre’s “ingenious and experienced prompter,”5 to train Betty for the stage. In a critical, if unsurprising, development, Hough steered his young charge away from Siddons and Elvira, thereby forestalling any risk of the boy overidentifying with the actress and her repertoire. Instead, Hough prepared Betty to embody a range of tragic warrior heroes, including Osman, Young Norval in Douglas, Rolla in Pizarro, and Achmet (Selim) in Barbarossa, John Brown’s tragedy about the Algerian ruler. Such roles indulged theatregoers’ orientalist and imperialist fantasies,6 while inviting them to compare the boy with the leading male actors of the day. In this way, Hough aligned Betty with the ideals of Romantic masculinity and the demands of empire, creating a template that later child actors would follow.

Following his Belfast debut,7 Betty embarked upon a series of provincial tours, performing in Dublin, Cork, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Birmingham, Sheffield, and Liverpool, where large audiences greeted him with excitement bordering on hysteria.8 It was during this period that Betty (presumably under Hough’s guidance) first introduced Richard III into his repertoire. A review from an August 1804 appearance in Birmingham noted that “the variety of conflicting passions which the crook-backed tyrant at all times was a prey to, were depicted by the young Roscius in the most able manner.”9 Here, the critic compares Betty to the first-century Roman actor Quintus Roscius Gallus, who was so widely lauded in his time that his name became an “honorary epithet” for subsequent generations of actors.10 Another newspaper described how audiences responded in astonishment to his death scene, wherein Betty as Richard “gnash[ed] his teeth in such a manner, as to give the highest promise of future excellence!”11 Tellingly, the critic acknowledges Betty’s potential, while hinting that the boy is not yet ready for such a challenging role.12

FIGURE 2. Master William Henry West Betty. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

After a year spent touring the provinces, Betty made his London debut at Covent Garden in December 1804. London audiences swarmed the theatre, primed by the glowing tributes and word-of-mouth accounts that had preceded his arrival. They were not disappointed. Critics praised Betty’s technical skill, his “bold, correct and grace[ful]” attitudes, his “striking and elegant” posture, and his convincing portrayal of strong emotion. His admirers included the Prince of Wales, the Duchess of York, and other members of the royal household, as well as the Prime Minister and members of Parliament.13 Thanks to a loophole in his contract with Covent Garden, Betty also played at Drury Lane during his London engagement, doubling the public’s opportunities to see him.14

Theatre historians have long wondered at the underlying factors that fueled Bettymania. Some scholars echo Kristina Straub in attributing the boy’s popularity to his physical attractiveness and charisma, noting the hype that surrounded each performance, the number of male and female theatregoers who purchased goods bearing his image, and the crush of fans that gathered outside his home and followed him on his travels.15 Commenting on claims that Betty’s Richard III “gratified the female part of the audience,” Jim Davis opines that women (and men) may have been aroused watching “the implicit sexual ‘otherness’ of Richard embodied and mediated through the ‘innocent’ child performer.”16 Childhood in this context is read through the body of a (pre)pubescent boy whose attractiveness arises from the startling juxtaposition of his onstage character with his real-world self, a self that is seemingly innocent, both morally and sexually. However, an emphasis on Betty’s appearance alone does not account for the range of responses he elicited. While some audiences expressed combinations of maternal and sexual desire for the boy, others viewed him as a refreshing escape from the anxieties of war and the threat of a Napoleonic invasion.17 George Taylor reads Bettymania “as a sign that people do indeed turn to the theatre in times of crisis, not necessarily to see their concerns enacted, debated or rehearsed, but to escape from anxiety.”18 Jeffrey Kahan concurs, observing that London newspapers devoted more column inches to covering Betty’s December 1804 debut than to Napoleon’s coronation as emperor of France the same week.19 This was no accident. Betty’s widespread popularity with Londoners and the surging crowds that greeted his performances at Drury Lane and Covent Garden gestured toward the public’s brewing dissatisfaction with contemporary politics and a surge in pro-revolutionary critiques of royalty and the aging aristocracy. As a “symbol of juvenescence,” Betty offered an appealing alternative to the decadence, disease, and corruption that characterized the nation’s rulers.20 Through his portrayal of Romantic heroes, men willing to sacrifice themselves for family and nation, he invited theatregoers to imagine their own “man of destiny.”

Public hunger for youth and vitality, fueled by the production and circulation of goods bearing his name and his own frequent theatrical appearances, transformed Betty from a charming boy into a celebrity.21 Betty’s audience avidly consumed his image22 and indulged in gossipy tidbits about his private life. “The attraction of the young Roscius is not limited to the stage,” claimed one report, “for he cannot walk along the streets without drawing crowds, who naturally press after him.”23 Here the desire to see the boy stretched beyond love and admiration to include stalking and other threatening behavior. Those unable to get tickets to see Betty perform would wait in the street outside his Southampton row house, hoping to catch “a peep before his drawing-room curtain!”24 Pushing beyond public into private space, the crowds pursued Betty with a hunger tinged with violence. The harder it became to access Betty’s physical person, the more desirable he became.

The hysteria surrounding Betty suggests that the boy possessed the requisite balance of “contradictory qualities” that Joseph Roach identifies as critical to the full flowering of the “It-Effect”: onstage he appeared as a strong, valiant warrior; offstage he was a cute child in need of support.25 This aspect of Betty’s celebrity became dramatically apparent when the boy fell ill and had to cancel several scheduled performances. Audiences were so overcome with worry that the Drury Lane management published a notice with letters from Betty’s father and doctor verifying the young boy’s illness, complete with vivid details of “bilious vomiting” and “cold and hoarseness” that rendered his voice barely “audible in his room.”26 London papers followed suit, publishing regular updates on Betty’s progress, with graphic accounts of the specific treatments administered (e.g., enemas, bloodletting), while Betty’s family posted notices outside their door to address the “numerous and incessant enquiries of the Nobility and Gentry.”27 This intense interest in Betty—the public’s demand to know everything that was happening to his body behind closed doors—hints at the ugly underbelly of celebrity culture. Such extreme reactions to Betty’s ill health also highlight the role of vulnerability, weakness, and distance in the accentuation of cuteness, an “aesthetic category” associated with smallness, delicacy, pliancy, and defenselessness.28 Although, as cultural historian Lori Merish asserts, “what the cute stages is, in part, a need for adult care,”29 the cute can also arouse feelings of possession and domination. When Betty became sick, his already attractive boy body became the focus of public scrutiny and heightened desire, a desire further stoked by his sudden inaccessibility. Hidden in the inner sanctum of his bedroom, Betty was literally untouchable, even by members of th...