![]()

The William Booth Memorial Home

Melbourne

20 December 1965

1.30 pm. John Buckle, a boarder at the William Booth, was furious. He was going to teach them a lesson. He smashed the radio, then the alarm clock. The remnants were strewn across his second floor room.

He was not going to let the men of the William Booth make fun of him anymore and he knew how to get their attention. A fire was a suitable punishment — that would make them think twice, for sure.

Buckle fetched a newspaper and ripped it to pieces, carefully placing the shreds on the floor next to his bed. Next, he pulled the bed sheets and blankets off the bed and placed these onto the pile. With sufficient fuel, he lit the paper and stood back.

The paper caught fire quickly, the blanket more slowly. However, within 30 seconds, the fire was established and his work was done. Buckle left the room but stayed on the second floor just to make sure someone noticed. Once the fire was discovered, Buckle left the building.

The fire grew to include the adjacent flooring, mattress and wardrobe to which it caused extensive damage but early detection enabled the fire to be extinguished quickly. The only damage was to Buckle’s rented cubicle and reputation; he would spend six months in jail.13

This was not the first fire at the William Booth. There had been at least ten earlier fires: several in the men’s private rooms, one in the kitchen, another in a lift and ironically one next to a fire hydrant.14 There had never been any casualties and there was no reason to expect one, the building met all the fire codes.

Fatefully however, with this latest fire, the staff of the men’s home had learned a questionable lesson. They believed they were able to control a fire without contacting the fire brigade.

13 August 1966

Some say it was a typical Melbourne August day, cold and wet. For Kelvin Fitness, the nightwatchman at the William Booth Memorial Home, the expectation was for a typical working day. Officially starting at 9.30 pm, his role was to survey the building every hour to make sure everything was in order. During his time there, the nights had been remarkably free of incident but this night was to become a night to remember.

Brought up in a Salvo family (with his father a Brigadier) it was almost inevitable he would land such a role. He had come from New Zealand to Melbourne for a short visit, which had now stretched to a year. Fitness enjoyed the work and as a bonus, he had somewhere to stay. He slept on the third floor, on the opposite side to where the trouble would begin. Fitness loved playing the cornet with the South Melbourne Army Corps and was not a bad singer either, sometimes accompanying one of the residents on the ground floor piano.

Kelvin Fitness and Wife

Kelvin Fitness

Also present was Major Reiger, the Assistant Manager of the William Booth. Very likeable, he and his wife went out of their way to help the appreciative nightwatchman. Major Reiger was strict, an essential attribute in dealing with the alcoholism but he was fair and had a good rapport with both clients and staff. Things had to be right: follow his rules and you were given a chance, play up and you were out.15 One of the residents he had a close eye on was a brandy drinker on the third floor, Vincent Gregory Fox.

Vincent Fox was born in 1903 in Hobart. A qualified pharmacist he enlisted for military service in 1942. He was initially attached to the 111 Australian General Hospital (AGH) in Tasmania and then the 107 AGH in Darwin. He is believed to have still been working as a chemist at the time of the fire. In March 1942, Fox was given a severe reprimand with ‘conduct prejudice of good order’ but further details of his behaviour are not specified.16 Of average height, 5 feet 6 inches, he had ginger hair and prominent gold teeth. He was severely overweight in 1966, carrying 14 stone and had significant heart disease.

Fox was a creature of habit, a drinking habit. At 5.00 pm on most days, but always on this day, a Saturday, he opened his cubicle door on the third floor to make his brandy pilgrimage from the William Booth, his residence of the last few years.

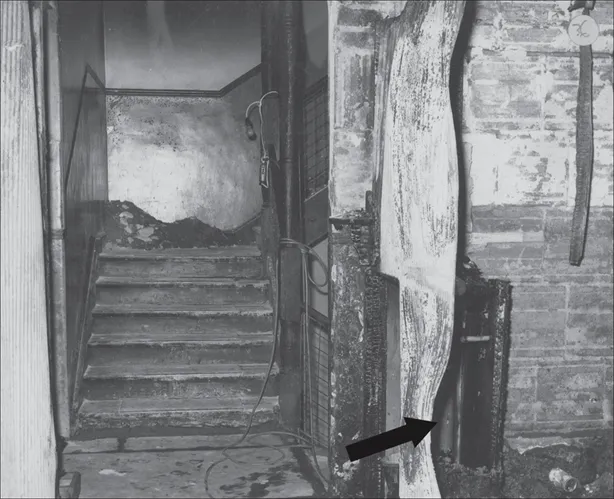

As Fox stepped out of the room, he could almost touch the floor’s firefighting equipment. A few feet to his right and abutting his room was a recess housing both a 2.5 inch canvas fire hose and an extinguisher. They looked modern and well-maintained and in fact, they were checked every six months by the Melbourne Fire Brigade.

The hose was connected to a ‘wet riser’ — a pipe filled with water from the street water main. It was capable of delivering a powerful torrent of 48 pounds17 of pressure in an instant, with a simple turn of the tap, enough to quell an incipient fire.

Next to the fire hydrant (known as a millcock) was the fire escape. Adjacent to Fox’s room was the southern stairwell, which led directly to the ground floor three flights below. The hydrants were located next to the front and rear staircases for a good reason — to be within easy reach of the fire brigade. There was another advantage with this arrangement, if a floor was inaccessible due to fire, the brigade could run a hose from the level below.

Wet Riser in the Fire Fighting Recess Next to Fox’s Room

Coroner’s Report

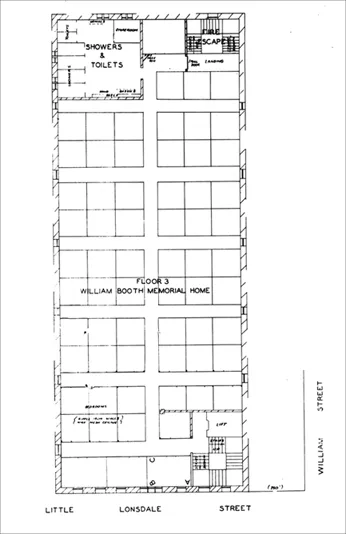

In the event of a blaze Fox would be in the safest location in the building, he had direct access to both the fire escape and firefighting equipment. This was important, as 64 private rooms were jammed into the third floor, a pattern replicated on the first, second and fourth stories.18 The rooms, although private, were tiny, measuring 7 feet 6 inches square, enough to fit a bed and few clothes but little else. The cubicles were grouped into lots of six on both sides of a north to south passage. They were accessed by narrow dead end passages running west to east. They were in fact rooms within a room. The cubicles were temporary structures within the cavernous space of each floor. With a height of 7 feet 6 inches, there was an 11 foot gap between the top of each cubicle and the floor ceiling. A rabbit warren would be a valid description of this set-up, but under the lodging standards of the day it was completely legal and more than the government could offer. The men did not complain, they were grateful to have a space they could call home.

3rd Floor Layout. Fox’s Room is Labelled ABC

Coroner’s Report

Fox paid no attention to the fire suppression equipment; his focus was on his next drink and the lift across the passage from the fire equipment. Fox entered the lift exiting on the bottom floor and then the home, passing under a large portrait of William Booth and into the frigid street.

Fox was not one for conversation but would say hello to the residents. He was unremarkable in this regard. Many residents kept to themselves, there were troubled pasts that they preferred to forget.

Fox made his way to his watering hole, the Metropolitan Hotel on the corner of William and Little Lonsdale Streets, only a few minutes’ walk away. It was the Booth residents’ pub of choice and for many their second home.

David Ferguson, an employee of the British Phosphate Commission, had also lived at the Salvos home for several years and lived directly above Fox on the fourth floor.19 He had returned to the William Booth from a football game at 2.00 pm and slept in the afternoon. When he awoke, he also made his way to the Metropolitan Hotel for a b...