![]()

P A R T I

STRATEGY STATICS

![]()

C H A P T E R 1

SCALE ECONOMIES

SIZE MATTERS

Netflix Cracks the Code

This chapter begins our journey together to construct the 7 Powers. It and the six that follow will each cover one of the seven Power types. I start with Scale Economies and illustrate this Power with Netflix.

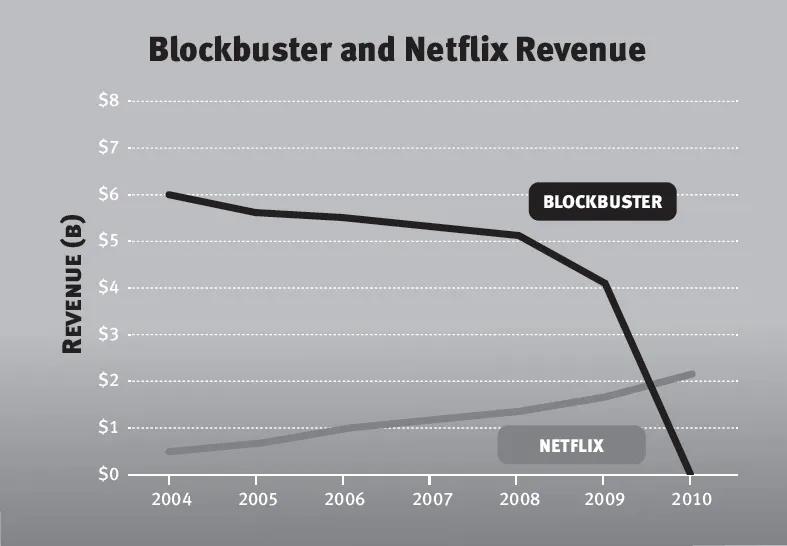

In the spring of 2003 I took a leap by investing in a small early-stage company based in Los Gatos, California. Today you may recognize the name: Netflix. Most of my investments have been in large caps, but I made this bet on Netflix due to their impressive mail-order DVD-rental business which was successfully disintermediating Blockbuster’s brick-and-mortar business model. Blockbuster faced the unpleasant choice of losing market share or eliminating late fees, which accounted for about half of their income. The investment hypothesis was grounded in this dilemma: Blockbuster would drag their feet facing up to the painful existential imperatives that confronted them and Netflix would continue to cannibalize their customers.14

This hypothesis was borne out by Blockbuster’s subsequent behavior and their eventual demise.

Figure 1.1: Blockbuster and Netflix Revenue15

As discussed in my Introduction, a strategy must meet the high hurdle of “A route to continuing Power in a significant market.” Netflix’s DVD-by-mail business made the grade, and it was their Power over Blockbuster that sealed the deal.

But there was a long-term time fuse to this mail distribution business. Why? The physical DVD business would eventually be supplanted by digital streaming distribution. The timing was uncertain, but Moore’s Law, coupled with the meteoric advances in Internet bandwidth and capability, guaranteed this outcome. The digital future was rising over the horizon, and Netflix could see it. There’s a reason, after all, they hadn’t dubbed their company Warehouse-Flix.

Streaming is a strategically separate business from DVDs by mail. By that I mean that the drivers of Power in each are largely orthogonal: different industry economics and different potential competitors. And streaming’s Power prospects were not that encouraging: plummeting IT costs and rapid advances of cloud services suggested diminishing barriers. Anyone, it seemed, could set up a streaming business.

Netflix understood this but remained undaunted. First of all, they realized they had no choice but to embrace streaming; as astute strategists, they knew that if they didn’t obsolete themselves, someone else would do it to them. And they were tactically smart. Given the uncertainty inherent in this emerging field, they took their time, demurring on high-testosterone bet-the-company antics. Instead, they modestly eased into streaming in 2007, hoping to test the waters and gain the needed experience. They accompanied this with much painstaking legwork, partnering with a dizzying array of electronic hardware streaming platform makers.

But deploying smart tactics, though complex and demanding, is not itself a strategy, and indeed any potential for Power remained opaque in those early days. For the time, Netflix could only stay alert and hope that Pasteur’s dictum would eventually bear fruit and chance would favor their prepared minds.

For Netflix, the crucial insight didn’t snap into focus until 2011, fully four years after they started streaming. Up till then, Netflix had negotiated with content owners (film studios being the chief example) for streaming rights. But these content owners were very savvy about monetizing their properties—they sliced and diced these rights by geographical region, release date, duration of the agreement, and so on. Ted Sarandos, Netflix’s Chief Content Officer, came to believe that it was vital the company secure exclusive streaming rights to certain properties. Here now Netflix finally made a radical move: a major resource commitment to originals, starting with House of Cards in 2012.

On the face of it, Netflix’s moves looked risky, overly ambitious. Creating originals, and thus tying up all the rights to that content, was more expensive. Further, Netflix had previously been down the road of original content with its Red Envelope Entertainment, and the results weren’t pretty. So too did it seem now that such forward integration might prove “a bridge too far.”

But these bold, counter-intuitive moves proved game-changing. Exclusive rights and originals made content, a major component of Netflix’s cost structure, a fixed-cost item. Any potential streamer would now have to ante up the same number of dollars, regardless of how many subscribers they had. If, say, Netflix paid $100M for House of Cards and their streaming business had 30M customers, then the cost per customer was three dollars and change. In this scenario, a competitor with only one million subscribers would have to ante up $100 per subscriber. This was a radical change in industry economics, and it put to rest the specter of a value-destroying commodity rat race.16

Scale Economies—the First of the 7 Powers

The quality of declining unit costs with increased business size is referred to as Scale Economies. It is the first of the 7 Powers I will examine, and its conceptual lineage begins with Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and indeed the beginnings of Economics itself.

Why do Scale Economies result in Power? Let’s recall the conditions for Power laid out in the Introduction. Power is a configuration that creates the potential for persistent significant differential returns, even in the face of fully committed and competent competition. To fulfill this, two components must be simultaneously present:

- A Benefit: some condition which yields material improvement in the cash flow of the Power wielder via reduced cost, enhanced pricing and/or decreased investment requirements.

- A Barrier: some obstacle which engenders in competitors an inability and/or unwillingness to engage in behaviors that might, over time, arbitrage out this benefit.

For Scale Economies, the Benefit is straightforward: lowered costs. In the case of Netflix, their lead in subscribers translated directly in lower content costs per subscriber for originals and exclusives.

The Barrier, however, is subtler. What prevents other firms from competing this away? The answer lies in the likely interplay of well-managed competitors. Suppose a company has a significant scale advantage in a Scale Economies business. Smaller firms would spot this advantage, and their first impulse might be to pick up market share, thus improving their relative cost position and erasing some of this disadvantage while improving their bottom line. To get there, however, they would have to offer up better value to customers, such as lower prices.

In an established market, such tactics are visible to the leader, who would realize the threat of reducing their relative scale advantage; they would retaliate by using their superior cost position as a defensive redoubt (matching price cuts for example). After several bouts of this, a follower will come to expect such retaliation and build it into their financial models for the impact of gain-share moves. For them, such moves would inevitably destroy value, rather than create it.

Intel’s microprocessor business that I discussed in the Introduction is a good example of how this plays out. Intel developed Scale Economies in the microprocessor business. Over a very long period, they were doggedly challenged by Advanced Micro Devices in this space. The outcome: a continuingly great business for Intel and persistent pain for AMD—at every turn Intel could fight off AMD relying on the economics rooted in its Scale Economies.

This unattractive cost/benefit is itself the Barrier for Scale Economies. Of course, it goes without saying: the Barrier must be thoughtfully maintained by the incumbent leader, but to bet on anything else would be foolish. So we see that Scale Economies satisfy the sufficient and necessary conditions for Power.

Scale Economies: Benefit: Reduced Cost

Barrier: Prohibitive Costs of Share Gains

This situation creates a very difficult position for Netflix’s smaller-scale streaming competitors. If they offer the same deliverable as Netflix, similar amounts of content for the same price, their P&L will suffer. If they try to remediate this by offering less content or raising prices, customers will abandon their service and they will lose market share. Such a competitive cul-de-sa...