Small Countries, Big Diplomacy

Laos in the UN, ASEAN and MRC

- 142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This book shows how small countries use "big" diplomacy to advance national interests and global agendas – from issues of peace and security (the South China Sea and nuclearization in Korea) and human rights (decolonization) to development (landlocked and least developed countries) and environment (hydropower development). Using the case of Laos, it explores how a small landlocked developing state maneuvered among the big players and championed causes of international concern at three of the world's important global institutions – the United Nations (UN), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Mekong River Commission (MRC).

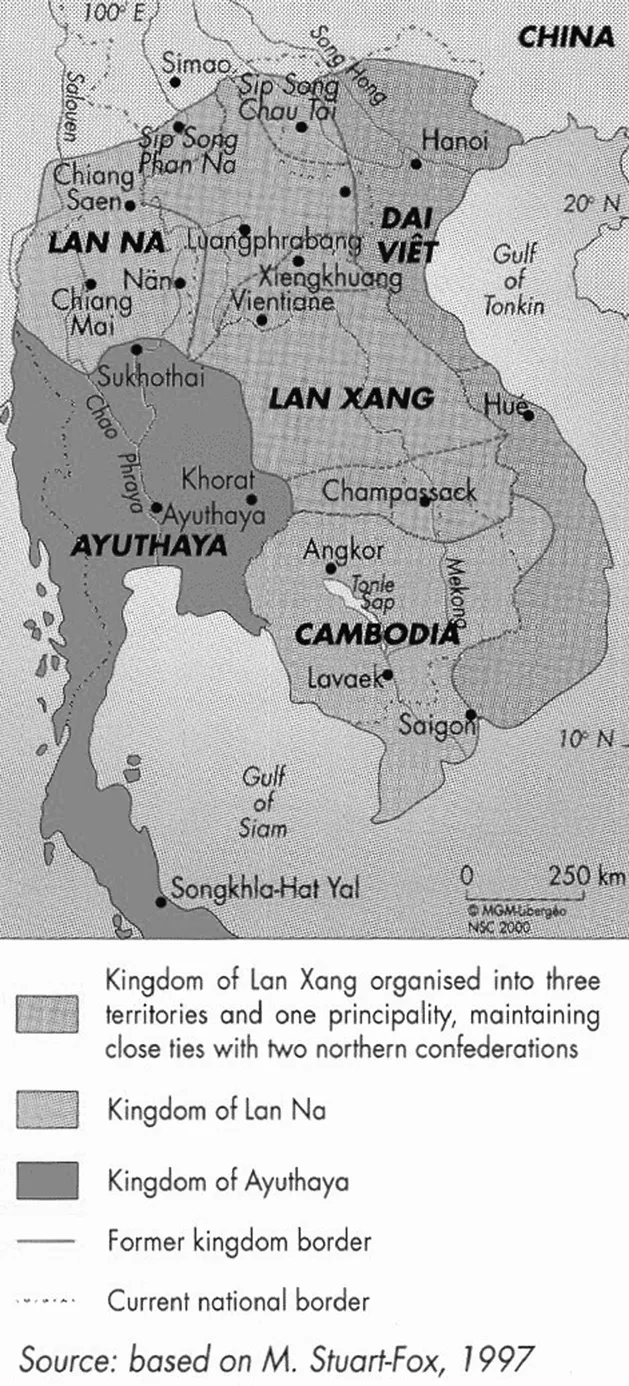

Recounting the geographical and historical origins behind Laos' diplomacy, this book traces the journey of the country, surrounded by its five larger neighbors China, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar and Cambodia, and influenced by superpower rivalries, from the Cold War to the post-Cold War eras. The book is written from an integrated perspective of a French-educated Lao diplomat with over 40 years of experience in various senior roles in the Lao government, leading major groups and committees at the UN and ASEAN; and the theoretical knowledge and experience of an American-trained Lao political scientist and international civil servant who has worked for the Lao government and the international secretariats of the UN and MRC. These different perspectives bridge not only the theory-practice divide but also the government insider-outsider schism.

The book concludes with "seven rules for small state diplomacy" that should prove useful for diplomats, statespersons, policymakers and international civil servants alike. It will also be of interest to scholars and experts in the fields of international relations and foreign policies of Laos, the Mekong and Asia in general.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

1

The origins of Laos’ brand of diplomacy

Geographical, historical and ideational

A small but strategic place

Complicated historical relationships

The structure and symmetry are admirable … truly it is of prodigious size, so large one would take it for a city, both with respect to its situation and the infinite number of people who live there … and that he … could write a whole volume if [he] tried to describe exactly all the other parts of the palace, its riches, apartments, gardens, and all the other similar things.10

Same same but different: the Lao and Siamese

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Information

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- About the authors

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction: Do small states matter in global institutions?

- 1 The origins of Laos’ brand of diplomacy: Geographical, historical and ideational

- 2 Navigating the Cold War1

- 3 Shaping global issues and policies at the United Nations1

- 4 Embracing and leading ASEAN1

- 5 Leveraging the Mekong River Commission to advance national and international agendas1

- Conclusion: Seven rules for small state diplomacy

- Index