- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Globalization has an ever-increasing effect on our lives. It has made the world smaller and brought us closer together yet it can also make us more vulnerable and divided. The deregulation of finance and banking and the crisis they led to is a devastating example of the knock-on effects of globalization.

This fully revised fourth edition reviews the history and complexities of globalization, examining the forces in play and whose interests they serve. And while the global exchange of people, products, plants, animals, technologies, and ideas intensifies the key question that Wayne Ellwood asks 'how can globalization be a positive force for change?'

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Globalization by Wayne Ellwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Globalisation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Globalization then and now

Globalization is a relatively new word which describes an old process: the integration of the global economy that began in earnest with the launch of the European colonial era five centuries ago. But the process has accelerated over the past 30 years with the explosion of computer technology, the dismantling of barriers to the movement of goods and capital, and the expanding political and economic power of transnational corporations.

More than five centuries ago, in a world without electricity, cellphones, antibiotics, refrigeration, wifi, automobiles, jet aircraft or nuclear weapons, one man had a foolish dream. Or so it seemed at the time. Cristóbal Colón, an ambitious young Genoese sailor and adventurer, was obsessed with Asia – a region about which he knew nothing, apart from unsubstantiated rumors of its colossal wealth. Such was the strength of his obsession (some say his greed) that he was able to convince the King and Queen of Spain to bankroll a voyage into the unknown across a dark, seemingly limitless expanse of water then known as the Ocean Sea. His goal: to find the Grand Khan of China and the gold that was rumored to be there in profusion.

Centuries later, Colón would become familiar to millions of schoolchildren as Christopher Columbus, the famous ‘discoverer’ of the Americas. In fact, the ‘discovery’ was more of an accident. The intrepid Columbus never did reach Asia – not even close. Instead, after five weeks at sea, he found himself sailing under a tropical sun into the turquoise waters of the Caribbean, making his landfall somewhere in the Bahamas, which he promptly named San Salvador (the Savior). The place clearly delighted Columbus’ weary crew. They loaded up with fresh water and unusual foodstuffs. And they were befriended by the island’s indigenous population, the Taíno.

‘They are the best people in the world and above all the gentlest,’ Columbus wrote in his journal. ‘They very willingly showed my people where the water was, and they themselves carried the full barrels to the boat, and took great delight in pleasing us. They became so much our friends that it was a marvel.’1

Twenty years and several voyages later, most of the Taíno were dead and the other indigenous peoples of the Caribbean were either enslaved or under attack. Globalization, even then, had moved quickly from an innocent process of cross-cultural exchange to a nasty scramble for wealth and power. As local populations died off from European diseases or were literally worked to death by their captors, thousands of European colonizers followed. Their desperate quest was for gold and silver. But the conversion of heathen souls to the Christian faith gave an added fillip to their plunder. Eventually European settlers colonized most of the new lands to the north and south of the Caribbean.

Columbus’ adventure in the Americas was notable for many things, not least his focus on extracting as much wealth as possible from the land and the people. But, more importantly, his voyages opened the door to 450 years of European colonialism. And it was this centuries-long imperial era that laid the groundwork for today’s global economy.

Colonial roots

Although globalization is now a commonplace term, many people would be hard-pressed to define what it actually means. The lens of history provides a useful beginning. Globalization is an age-old process and one firmly rooted in the experience of colonialism. One of Britain’s most famous imperial spokespeople, Cecil Rhodes, put the case for colonialism succinctly and brazenly in the 1890s. ‘We must find new lands,’ he said, ‘from which we can easily obtain raw materials and at the same time exploit the cheap slave labor that is available from the natives of the colonies. The colonies [will] also provide a dumping ground for the surplus goods produced in our factories.’2

During the colonial era European nations spread their rule across the globe. The British, French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Belgians, Germans, and later the Americans, took possession of most of what was later called the Third World. And of course they also expanded into Australia, New Zealand/Aotearoa and North America. In some places (the Americas, Australia, New Zealand and southern Africa) they did so with the intent of establishing new lands for European settlement. Elsewhere (Africa and Asia) their interest was more in the spirit of Rhodes’ vision: markets and plunder. From 1600 to 1800 incalculable riches were siphoned out of Latin America to become the chief source of finance for Europe’s industrial revolution.

Global trade expanded rapidly during this period as colonial powers sucked in raw materials from their new dominions: furs, timber and fish from Canada; slaves and gold from Africa; sugar, rum and fruits from the Caribbean; coffee, sugar, meat, gold and silver from Latin America; opium, tea and spices from Asia. Ships crisscrossed the oceans. Heading towards the colonies, their holds were filled with settlers, administrators and manufactured goods; returning home, the stout galleons and streamlined clippers bulged with coffee, copra, cotton and cocoa. By the 1860s and the 1870s world trade was booming. It was a ‘golden era’ of international commerce – though the European powers pretty much stacked things in their favor. Wealth from their overseas colonies flooded into France, England, Holland and Spain while some of it also flowed back to the colonies as investment – in railways, roads, ports, dams and cities. Such was the range of global commerce in the 19th century that capital transfers from North to South were actually greater at the end of the 1890s than at the end of the 1990s. By 1913 exports (one of the hallmarks of increasing economic integration) accounted for a larger share of global production than they did in 1999.

Expanding international trade

When people talk about globalization today they’re still talking mostly about economics, about an expanding international trade in goods and services based on the concept of ‘comparative advantage’. This theory was first developed in 1817 by the British economist David Ricardo in his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Ricardo wrote that nations should specialize in producing goods in which they have a natural advantage and thereby find their market niche. He believed this would benefit both buyer and seller but only if certain conditions were maintained, such as: 1) trade between partners must be balanced so that one country doesn’t become indebted and dependent on another; and 2) investment capital must be anchored locally and not allowed to flow from a high-wage country to a low-wage country.

Unfortunately, in today’s high-tech world of instant communications, neither of these key conditions exists. Ricardo’s blend of local self-reliance mixed with balanced exports is nowhere to be seen. Instead, export-led trade dominates the global economic agenda. The only route to increased prosperity, say the ‘experts’, is to expand exports to the rest of the world. The rationale is that all countries and all peoples eventually benefit from more trade.

When the world economic crisis erupted in 2008, international trade slumped for the first time in living memory. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), trade in Europe fell by nearly 16 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2008 while global trade fell by more than 30 per cent in the first quarter of 2009. But this was an anomaly. During the 1990s world trade grew by an average 6.6 per cent yearly and from 2000 on it averaged more than 6-per-cent growth a year. On average, trade after 1950 expanded twice as fast as world GDP. Unfortunately, most of this wealth ended up in the hands of the rich developed nations. They account for the lion’s share of world trade and they mostly trade with each other. According to the WTO, in 2013 Europe and North America together accounted for nearly 50 per cent of global merchandise exports and 61 per cent of commercial service exports.3

Tyranny and poverty

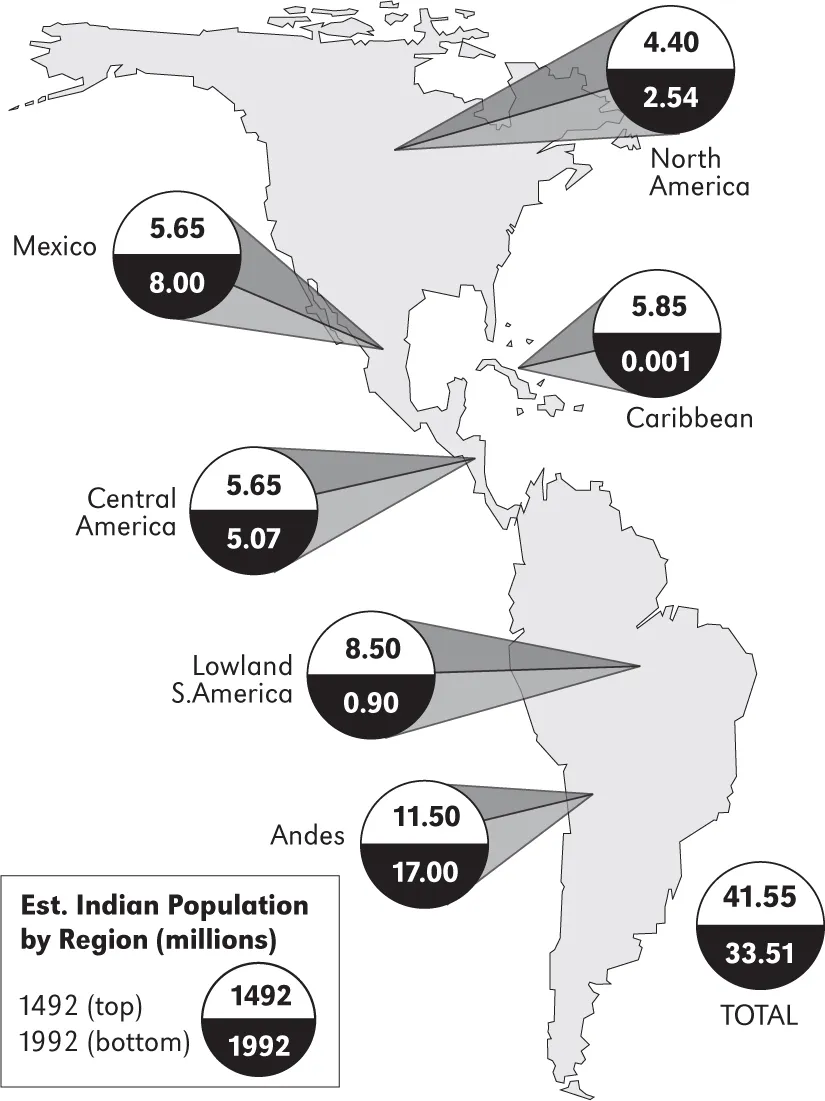

Colonialism in the Americas separated Indians from their land, destroyed traditional economies and left native people among the poorest of the poor.

•The Spanish ran the Bolivian silver mines with a slave labor system known as the mita; nearly eight million Indians had died in the Potosí mines by 1650.

•Suicide and alcoholism are common responses to social dislocation. Suicide rates on Canadian Indian reserves are 10 to 20 times higher than the national average.

•In Guatemala the infant mortality rate among indigenous people is 30% higher than for the non-indigenous population. Maternal mortality is almost 10 times higher among indigenous people. (cesr.org)

Indian Population of the Americas: 1492 and 1992

SEDOS Bulletin, Rome, May, 1990; The Dispossessed, Geoffrey York (Lester & Orpen Dennys, Toronto, 1989); Guatemala: False Hope, False Freedom, James Painter (CIIR, London, 1987); Ecuador Urgent Action Bulletin (Survival International, London, 1990); Native Population of the Americas in 1492, Ed. W. Denevan (University of Wisconsin Press, 1976) and GAIA Atlas of First Peoples, Julian Burger (Doubleday, New York, 1990).

Nonetheless, the world has changed in the last century in ways that have completely altered the character of the global economy and its impact on people and the natural world. Today’s globalization is vastly different from both the colonial era and the immediate post-World War Two period. Even arch-capitalists like currency speculator George Soros have voiced doubts about the values that underlie the direction of the modern global economy.

‘Insofar as there is a dominant belief in our society today,’ he writes, ‘it is a belief in the magic of the marketplace. The doctrine of laissez-faire capitalism holds that the common good is best served by the uninhibited pursuit of self-interest…Unsure of what they stand for, people increasingly rely on money as the criterion of value…The cult of success has replaced a belief in principles. Society has lost its anchor.’

The inefficient magic of the marketplace

The ‘magic of the marketplace’ is not a new concept. It’s been around in one form or another since the father of modern economics, Adam Smith, published his pioneering work The Wealth of Nations in 1776. (Coincidentally, in that same year, Britain’s 13 restless American colonies declared independence from the motherland.) But Smith’s concept of the market was a far cry from the one championed by today’s globalization boosters. Smith was adamant that markets worked most efficiently when there was equality between buyer and seller, and when neither was large enough to influence the market price. This, he said, would ensure that all parties received a fair return and that society as a whole would benefit through optimal use of its natural and human resources. Smith also believed that capital was best invested locally so that owners could see what was happening with their investment and could have hands-on m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Globalization then and now

- 2. The Bretton Woods trio

- 3. Debt and structural adjustment

- 4. The corporate century

- 5. Global casino

- 6. Poverty, the environment and the market

- 7. Redesigning the global economy

- Index