- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

No-Nonsense Guide to World Health

About this book

Here is a clear, wide-ranging introduction to the worldwide state of human health. Starting with a brief history of modern medical progress, Shereen Usdin then untangles the knot created by poverty and globalization to show that where you live, how wealthy you are, and your gender all have a bearing on the diseases you may encounter in your lifetime—and your prospects for prevention, treatment, and ultimately, survival.

Pulling no punches, Usdin also blows the whistle on the political economy of illness and how keeping people sick means more money for the pharmaceutical, tobacco, and food industries. This No-Nonsense Guide is a must-read for anyone who wants a clear sense of how healthy our global family really is.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No-Nonsense Guide to World Health by Shereen Usdin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Globalisation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

1 No ‘Health for All’ by the 21st century

‘Modern high-tech warfare is designed to remove physical contact: dropping bombs from 50,000 ft ensures that one does not “feel” what one does. Modern economic management is similar: from one’s luxury hotel, one can callously impose policies about which one would think twice if one knew the people whose lives one was destroying.’

Spectacular gains in life expectancy have taken place but the benefits have been unevenly distributed. Today’s world is beset with inequities exacting an enormous toll on health. The causes go way back but they have been deepened by macroeconomic policies imposed over the last few decades on the South. Serving the interests of the North they are in large part why WHO’s clarion call of ‘Health For All by the Year 2000’ remains a lofty dream.

If an alien were to land on earth today it would have a hard time explaining things to the mothership. It would flash back photographs of Citizen X, sipping mineral water in his luxury penthouse, followed by Citizen Y’s mother collecting water from a stagnant stream.i

Today, 1.1 billion people do not have access to adequate amounts of safe water and 2.6 billion lack basic sanitation,2 making hygiene impossible. Together they make Citizen Y vulnerable to a host of infections. She could be one of the 1.5 million children who die each year from diarrhea because of this.3 Because no health education ever reached her village, her mother does not know about lifesaving oral rehydration therapy. The clinic is too far to walk to and there is no money to pay for transport or the clinic visit.

If Citizen Y recovers, her chances of making it beyond her fifth birthday are slim. If infections don’t kill her, they could leave her blind or undernourished in her critical developmental years, with compromised physical and cognitive functioning. Disadvantaged at school, if she gets to go, what chance does she stand to perform well, graduate, get a job and escape the poverty she was born into? Poverty begets ill-health which begets poverty.

The alien would report that there is some trouble in paradise – living high on the hog makes Citizen X vulnerable to chronic diseases.ii But when he has his heart attack at 70 he will be rushed to a state-of-the-art hospital where the best medical team will work wonders.

We live in an era where spectacular things are possible. We’ve mapped the Human Genome, grown organ tissue from embryonic stem cells and may be close to cloning a human being. We can replace the human heart with an artificial one and do intricate surgery via computer. These are the days of ‘miracles and wonder’. But this offers little relief from the grinding poverty and ill-health experienced by almost half the world. They are the 2.8 billion people who live on less than $2 per day. In Ethiopia they are called wuha anfari – ‘those who cook water’.

Spectacular gains, spectacular inequity

Our hunter-gathering ancestors roamed the earth for 25 years on average. Major gains were only made in the mid-19th century and by the 1950s we were roaming on average for about 20 to 30 years more. Improvements in socio-economic conditions with better living standards (including water and sanitation provision) and nutrition were largely responsible for the dramatic gains in life expectancy in the mid-19th century. While these gains pre-dated larger public health interventions including oral rehydration therapy and immunization, some argue that the role of these technological interventions is understated.

Life expectancy shot up in the last half of the 20th century, spiking today at 80 years in some parts of the world.4 Continuing improvements in socio-economic conditions and better medical interventions, notably treatment of infections and prevention and control of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, have been largely responsible for gains post-1950.

What’s in a name?

Terminology describing countries’ varying degrees of ‘development’ is highly contested. This book tends to use ‘North’ and ‘South’, ‘Western’ and ‘Majority World’, ‘rich’ and ‘poor’, although they are all imperfect. For example, in 1990, the Fortune 500 included 19 transnational companies from the South. This rose to 57 in 2006. Journalist Thebe Mabanga quips: ‘World domination is now as likely to be plotted from an air-conditioned office in Mumbai as it is from New York’.

While the majority of the world is better off today than a century ago, these gains have been unequally distributed both between and within countries. In some parts of the world you would be lucky to make it to 40. Life expectancies have decreased in sub-Saharan Africa (largely because of HIV) and in the former Soviet Union (largely because of social disruption, increased poverty and the collapse of social services). In industrialized countries only 1 in 28,000 women will die from causes related to childbearing, while in sub-Saharan Africa the risk is 1 in 16. In wealthy Australia there is a 20-year gap in life expectancy between Aboriginals and the Australian average. Premature death in African-American men is 90 per cent higher than in whites.5

Inequitable and iniquitous

According to the UN Millennium Project’s Jeffrey Sachs the gap between rich and poor nations has been widening steadily from 12-fold in 1961, to 30-fold in 1997 with simultaneous disparities in life expectancy and infant mortality rates between and within countries.

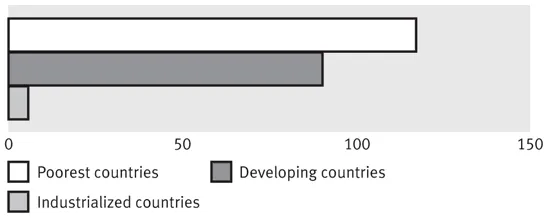

While under-5 mortality rates (the number of children dying under 5 years per 1,000 live births per year) declined overall, the rate of decline differed. Between 1990 and 2002 rates declined by 81 per cent in industrialized countries, 60 per cent in developing and 44 per cent in the poorest countries. This decline has stagnated and is reversing in some countries, particularly in Africa.

Under-5 mortality rates by country income level (per 1,000 live births)

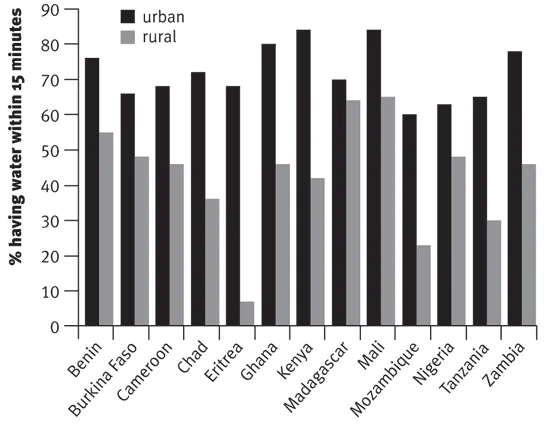

According to UNICEF global access to water increased from 78 to 83 per cent between 1990 and 2004. But this masks wide inter- and intra-country disparities particularly between urban and rural communities. In West/Central Africa for example, about 49 million people living in urban areas gained access to improved drinking-water sources during this period, but only 26 million people living in rural areas did so. In some countries the discrepancies are very high. For example, in Mongolia, 87 per cent of urban dwellers have access to safe water supplies while only 30 per cent of rural dwellers do.

Today’s global averages look less rosy when disaggregated by gender, race, geographical location or bank balance. These factors, plus others, are referred to as ‘the socio-economic determinants’ of health. Reflecting differing levels of social privilege, they determine your exposure to risk, your access to life opportunities and resources (including safe water and sanitation, education, and health services). They determine how long and how healthily you live.

It is no surprise that absolute deprivation has negative health outcomes. This is why more than 10 million children die of hunger and preventable diseases every year – astoundingly, one every three seconds. They die largely from a few poverty-related conditions: pneumonia, diarrhea-related diseases, malaria, measles, HIV/AIDS, under-nutrition and neonatal conditions. Most of these deaths happen in the South.

But inequality per se within societies is also thought to result in negative outcomes through perceptions of social deprivation, even when relatively small. Lack of social cohesion and inadequate political support for redistributive policies in such societies are also thought to be responsible.

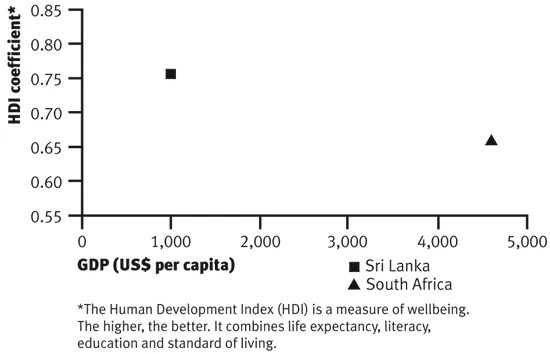

Economic growth and good health are not automatically synonymous

Once a minimum per capita income is achieved, education and other socio-political investments have greater health impacts than economic growth.* This is why poorer countries with less inequality often score better on health measures than wealthy counterparts with greater inequality. Sri Lanka for example scores higher on the Human Development Index* than South Africa which has a 4-fold higher per capita GDP but is one of the world’s most unequal countries.

GDP vs HDI

In fact poorer countries with less inequity often have equal or better health measures than wealthy countries with large disparities. For example, Sri Lanka and India’s Kerala state are both poor, but have limited income variation and invested heavily in redistributive, pro-equity policies. Basic curative and preventive health services were combined with strategies to ensure land reform, universal access to housing, education (emphasizing gender equity), subsidized school transport and nutrition, water, sanitation and extensive social safety nets.

Kerala’s per capita income is about a hundredth that of wealthier countries. It spends $28 per capita on health compared to the US which spends $3,925. But life expectancies of 76 for women and 74 for men are roughly on par with those in the US (80 and 74 years respectively).6 Infant Mortality Rates (IMR) in Kerala at 14 per 1,000 live births are close to the US average rates (7 per 1,000). But citizens of Kerala fare better than African-Americans whose IMRs are well below the US average. They also fare better than those in equally poor parts of India where average IMRs are 68 per 1,000.

Health equity means ‘any group of individuals defined by age, gender, race-ethnicity, class or residence is able to achieve its full health potential.’7 Addressing poverty and inequity is unequivocally the greatest challenge facing public health in the 21st century.

Beneath the rosy surface

According to UNICEF, global access to water increased from 78 per cent in 1990 to 83 per cent in 2004. But this masks wide inter- and intra-country disparities, particularly between urban and rural communities. One inequity leads to another – studies show that girls miss days of learning during their menstrual periods or drop out of school entirely as a result of lack of privacy, where schools lack separate water and sanitation facilities for them.

Urban-rural differences in access to water supply

So how did it get to be this way?

Simply put, the haves have, because everyone else has not. Since the days when sea-faring adventurers set forth to pillage and plunder, the world has been a bargain bin for wealthy nations. For the vanquished, life was cheap and full of hardship. Entire civilizations were wiped out. Later forms of colonialism were equally cruel. In the 1890s, Cecil John Rhodes, mining magnate and politician in South Africa, said shamelessly: ‘We must find new lands from which we can easily obtain raw materials and at the same time exploit the cheap slave labor that is available from the natives in the colonies. The colonies [will] also provide a dumping ground for the surplus goods produced in our factories’.8 By the mid-20th century, colonial powers were still sucking countries dry of resources, expropriating land from peasants for large-scale cultivation to feed the empires and lowering local food production. People were worked to death or spat out when they were sick and dying. Over a century later, modern forms of colonialism, dressed in the rhetoric of ‘the free market’ are doing the same. But more on that later.

While the health of the colonized deteriorated, two tiers of health services prevailed – quality services for the élites and third-rate care for the rest. Services were based in urban areas, and largely curative in nature.

The right to health

‘General Comment 14’, added to the UN’s International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights in 2000, states that the right to health is ‘an inclusive right extending not only to timely and appropriate health care, but also to the underlying determinants of health, such as access to safe and potable water and adequate sanitation, an adequate supply of safe food, nutrition and housing, healthy occupational and environmental conditions and access to health-related education and information, including on sexual and reproductive health’.

In 1948, in the idealistic aftermath of the Second World War, the United Nations (UN) was born, and with it came global acknowledgements of health as a human right linked inextricably to social and economic justice. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights held that ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.’ The 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (and more recent additions) elaborated on this even further (see box: The right to health). The World Health Organization (WHO) was established as the UN’s specialized health agency to serve as the world’s ‘health conscience’ and safeguard this inalienable right to health. It defined health as a state of wellbeing, not simply the absence of disease.

If there was no poverty...

During the 1980s, the richest 1 per cent in the US increased their share of the country’s wealth from 31 to 37 per cent. Yet in 1991 almost one-fifth of mortality in people between ages 25 to 74 was due to poverty.

Poverty’s impact on health

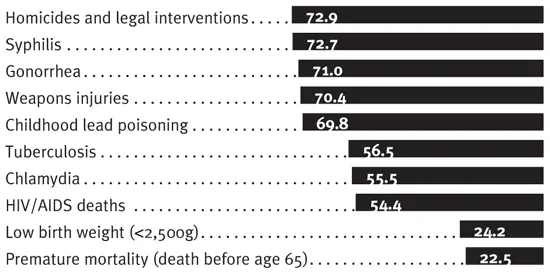

The Harvard Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project team calculated what would happen to the number of cases in their study if everyone faced the same risk as people who were living in areas where fewer than five per cent of residents were impoverished.

% of cases that would not have occurred

The rise of Primary Health Care (PHC)

Postcolonial concerns for health and social justice varied. In some countries the oppressor simply became ‘home-grown’. Inequities continued and even intensified. Many countries continued to follow the colonizers’ medical model of health care with costly urban hospitals and ‘doctors as God’. For others, radical change was in the air. With oppression came a strong consciousness of the lin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 No 'Health for All' by the 21st century

- 2 Globalization: the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

- 3 The politics of patents

- 4 The politics of gender

- 5 The emergence of old and new epidemics

- 6 Non-communicable 'pandemics': the high price of Big Business

- 7 The big fix

- Resources and contacts

- Copyright