- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

No-Nonsense Guide to Tourism

About this book

Many people like to take a break by exploring somewhere new, whether it's with just a backpack or with a fleet of luggage. But there is more to a holiday that visiting "attractions," sampling local foods, and napping in a hammock. Being a tourist is easy—tourism is complex.

In this No-Nonsense Guide, Pamela Nowicka explores the third largest industry in the world (after oil and narcotics) and its profound economic, social, and environmental impacts. Taking the reader on a trip from the early days of travel to the first package tours and on to today's mass tourism, she argues that without a greater commitment to equitable and sustainable practices, tourists of all stripes will continue to be part of the problem, not the solution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No-Nonsense Guide to Tourism by Pamela Nowicka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

1 What is tourism?

Everyone likes to go on holiday. The well-earned break is part of the fabric of Western lifestyle. Yet few holidaymakers are aware of the impact of this vast industry on people, environments and culture.

‘When we try to do business with Western people they say “No, no, no. We’ve just spent $10 going into the temple and we can’t afford more,” says Raj, a guide in South India. ‘So we don’t get any business.’ Raj’s words raise a key issue to do with tourism – who benefits?

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, formerly WTO), in 2004 worldwide earnings from international tourism reached a new record value of $623 billion (up from $478 billion in 2000; about 10 per cent of global GDP). In the same year an estimated 763 million people traveled to a foreign country (698 million in 2000).

Tourism activity is growing at an average annual rate of 6.5 per cent with the highest rates of growth in Asia and the Pacific regions. UK organization Tourism Concern estimates that it is the main money-earner for one third of ‘developing’ nations and the primary source of foreign exchange for 49 of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), with 14 of the top 20 long-haul destinations in developing countries.

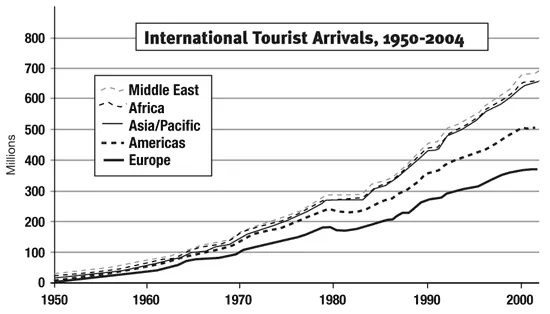

The growth of this industry has been sustained and meteoric: in 1950 tourism accounted for a ‘mere’ 25 million international arrivals; by 2004 it was 800 million and this figure is expected to double by 2015. An estimated 200 million people work in travel and tourism (T&T) and according to the UNWTO, ‘The substantial growth of tourism activity clearly marks it as one of the most remarkable economic and social phenomena of the last century.’ Tourism, it adds, is a human right, which can help alleviate world poverty and contribute to international understanding and world peace.

But how did it all start? And are the remarkable claims made for this sector by its advocates and lobbyists true – or an attempt to conceal the profit motive under a veil of altruism?

The travel bug

International arrivals have increased from 25 million in 1950 to 763 million in 2004, an average of 6.5 per cent per year. Fastest growth is in Asia and the Pacific, at 13 per cent per year.

In the beginning

For most of human history travel has, for most people, been a necessary evil. Those who traveled further afield than their own neighborhood tended to do so professionally, as soldiers or merchants. Others traveled with their herds. Now travel has been transformed from minority activity to something that is seen as almost a human right – for those from the rich countries. How has this transformation occurred?

A quest lies at the heart of travel: a search for Eldorado – the Land of Gold, or Paradise on Earth. Financial and territorial gain and a sense of something somewhere else that it is impossible to find at home have been the drivers of movement and exploration since people have set out beyond the normal confines of the place and land where they lived. However, not everyone has been convinced about the motives: ‘I do not much wish well to discoveries, for I am always afraid they will end in conquest and robbery,’ commented the writer Samuel Johnson in 1773.

The Greeks and the Romans traded regularly with India, with caravans traveling the Silk Road to central Asia, while Roman ships sailed to India using the monsoon winds. The Chinese, too, traveled and traded with what is now Indonesia and further afield.

Who travels?

The Eurocentric worldview is implicit in modern Western travel literature. From the outset, ‘we’ are traveling to the ‘other’. In the same way that, until relatively recently, cultures have tended to view the male as the norm and the female primarily as she relates to the male, non-Europe and its people is given the same relationship to Europe (and later North America). The implications of this ‘otherness’ continue in the complex set of interactions between tourists and their ‘hosts’ and are especially marked when people from rich countries visit the Majority World, the Global South, or ‘Third World’.

‘Unfriendly natives’

People who ventured beyond their own territory in ancient times were usually in search of something that would be of direct benefit to them – new land to occupy and cultivate, or resources such as timber, stone or minerals, or any goods they could not obtain at home... Starting with the expedition led by the Egyptian government official Herkhuf in about 2270 BCE there are a surprising number of records of ancient explorers who braved treacherous seas, hostile terrain, wild animals and unfriendly natives [sic] to discover new lands and bring back exotic goods.

Modern geographical texts still unselfconsciously use loaded concepts. Indigenous people are described as ‘natives’, and are ‘friendly’ or ‘unfriendly’. Trading entrepreneurs are described as ‘explorers’ and their friendliness or otherwise is never described, although there is often a reference to their bravery. ‘The natives’ are never described as brave.

The mystic East

According to historian Ronald Fritze: ‘Western knowledge of Asia was plagued from its beginnings by a highly inaccurate corpus of information known as the Marvels of the East. According to this body of geographical and cultural lore, India and East Asia were lands full of strange and astonishing peoples, plants, animals, places and things.’1

The inaccuracies he referred to resonate with today’s holiday brochures. But it is not only travel which is constructed through this sense of the ‘other’. The entire relationship between what are now called ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries, Rich and Poor countries, First and Third World/Majority World, or North and South has remained essentially the same for centuries. In travel literature and in our thoughts about travel and tourism, there continues what author Edward W Said described as ‘...this flexible positional superiority, which puts the Westerner in a whole series of possible relationships with the Orient without ever losing him [sic] the relative upper hand.’ This applies to all those non-European countries and their inhabitants, all those places whose people were, and surprisingly often still are, called natives.

The existence of China and its silk was known by the time of Pliny the Elder in 23-79 CE and there are reports of Romans and Han Chinese trying to establish direct contact between their two cultures, but nothing of substance came of these efforts. Instead, with the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire, Westerners turned away from the East.

However, with the Crusades in the 11th century, Europeans once again began to engage with China and other Far Eastern lands. The Spanish Jewish Benjamin of Tudela’s description of his travels during 1166-71 was the first book in Western Europe to mention China or a route to China.

The wishful thinking behind the Prester John legend (see box) highlights a continuing attitude by Europeans to the Majority World. For nearly a thousand years, dominion has been part of the collective psyche, both implicit and explicit. It has been an integral part of Western culture, and forms some of the cultural baggage which Europeans and North Americans take whenever we venture into the Majority World.

Prester John

During the era of the Crusades (11th-13th century), a legend arose concerning a powerful Christian ruler whose kingdom was located in Asia. It was hoped that this ruler, who was called Prester John, and his great armies would come to the aid of the beleaguered Crusaders in Palestine and destroy the forces of Islam.

The Letter of Prester John claimed that his kingdom encompassed the Three Indias... Its boundaries were unmeasurable... [it] was a land of milk and honey but it also produced valuable pepper. Its rivers were cornucopias of gold and jewels... [It] housed the Terrestrial Paradise [including] the four rivers of Paradise ... all of which were also filled with gold and precious stones. Near the Terrestrial Paradise was the much-sought-after Fountain of Youth, which some writers claimed accounted for Prester John’s apparently extreme longevity...

During the 14th and 15th centuries, as Asia became better known to Europeans as a result of the travels of Marco Polo and the many other Christian diplomats, merchants and missionaries, the location of Prester John’s kingdom shifted to Africa, specifically the Christian realm of Ethiopia.

The language of domination and acquisition so unselfconsciously and unquestioningly used in accounts of European journeys into non-European countries is fascinating in both its prevalence and consistency: ‘Various European explorers, traders and settlers began to venture onto the high seas of the Atlantic Ocean by the end of the 13th century. This geographical expansion was part of an extension of trading activities that had been taking place for some time.’1

Some authorities are more direct about the motives behind voyages of ‘exploration’. The historian JH Parry asserts that among the many and complex motives which impelled Europeans, and especially the peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, to venture overseas in the 15th and 16th centuries, two were obvious, universal and admitted: acquisitiveness and religious zeal.2

Demonic wonders

Historian Ronald Fritze articulates a mode of thinking, which is probably current in some circles:

Medieval Christian scholars had a ready explanation for why there were marvels in the eastern and southern lands but not in Christendom. According to William of Auvergne, who wrote in the 13th century, Europe lacked wonders because it was Christian. The demons responsible for amazing phenomenons [sic] no longer resided in Europe. In heathen lands, like India, demons still worked their magic and monsters, magic gems and strange plants still flourished.

Parry contextualizes the push for new territories and the process. Land and the labor of those who worked on it were the principal sources of wealth. The quickest, most obvious and socially most attractive way of becoming rich was to seize and hold as a fief land already occupied by a diligent and docile peasantry. For a long period Spanish knights and nobles had been accustomed to this process. And in most parts of Europe during the turbulent 14th and 15th centuries, such acquisition of land had often been achieved by means of private war.

However as rulers became stronger, the opportunities for private war decreased. But, for those keen on gaining riches, another way was possible: ‘The seizure and exploitation of new land – land either unoccupied or occupied by useless or intractable peoples who could be killed or driven away. Madeira and parts of the Canaries were occupied in this way in the 15th century, respectively by Portuguese and Spanish settlers.’

‘The Native Problem’

Perhaps unburdened by notions of political correctness, Parry lays bare the realities of opening up trade routes in terms which give a fair indication of the exploring Europeans’ mindset: ‘Precious commodities... might be secured not only by trade, but by more direct methods: by plunder, if they should be found in the possession of people whose religion, or lack of religion, could be made an excuse for attacking them; or by direct exploitation, if sources of supply were discovered in lands either uninhabited, or inhabited only by ignorant savages.’

These dynamics have been played out in centuries of wars and trading practices which are the backdrop to, and contribute to, the current rich world/poor world split. A few centuries ago, spices, gold and wood were on the colonial shopping list. More recently transnational corporations (TNCs) extract oil, gas and minerals from Majority World countries.

And some argue that tourism is as much an extractive industry as any of these, and that its impact on the environment is similar (see box ‘Tourism’s threats’).

Tourism’s threats

Uncontrolled conventional tourism poses potential threats to many natural areas around the world. It can put enormous pressure on an area and lead to impacts such as soil erosion, increased pollution, discharges into the sea, natural habitat loss, increased pressure on endangered species and heightened vulnerability to forest fires. It often puts a strain on water resources, and can force local populations to compete for the use of critical resources.

Westward Ho!

Returning to exploration, when Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama began their respective journeys in the 1490s they were seeking sea-routes to Asia to the spice markets. But Columbus’ efforts were halted by the vast land mass (the Americas) that stopped European vessels from sailing west to Asia. While this was initially disappointing, ‘new opportunities arose for Spain to conquer first Mexico and then Peru. Vast riches would flow into Spain as a result of these acquisitions.’

Vasco da Gama’s exploration of a route to India is described in similarly approving terms: ‘When da Gama returned to Lisbon from his voyage to India... he opened a world of potentially infinite wealth to King Manuel and the people of Portugal.’1

The impact of these activities on the people already living there is described: ‘Native American cultures and civilizations suffered conquest and destruction with many tribes becoming extinct.’ Portuguese sea commander, Pedro Cabal, who in the 16th century took Brazil for Portugal, found some indigenous people who were ‘quite friendly’. But their lack of knowledge about the existence of gold made the land ‘relatively worthless in the eyes of the Portuguese’.

Later, on the East African Coast, Cabal and his ships ‘encountered grudging hospitality from the Muslim cities... Signs were accumulating that the Muslim merchants of East Africa resented the arrival of Portuguese interlopers and feared the possible unfavorable future consequences for their commerce. The Portuguese further aggravated the situation by openly displaying their crusading attitudes and their assumptions of superiority.’1

The process of the ‘discovery’ of Africa was not helped by the difficult terrain and a ‘torrid climate which encouraged disease, to which these explorers often succumbed. Added to the dangers was the threat from hostile tribes – Europeans were sometimes killed.’3

The tone of mild dismay about the killing of interlopers bent on ransacking a country for their own benefit is not used to describe the killing of indigenous people.

Discovery and exploration

Later, in 1577, Englishman Francis Drake set out to sail round the world. Following raids on Spanish vessels – so successful that on the return his ship the Golden Hind was ballasted with gold and silver bullion rather than stones and clinkers – and a three-year trip via California, the Moluccas in Indonesia, and round the Cape of Good Hope, Drake returned to England and a knighthood. His backers realized a return of 5,000 per cent on their investment.4

The chain of exploration and exploitation continues to this day with foreign companies siphoning off the wealth from poorer countries, paving the way for rich world domination of poor countries in other ways such as colonization.

Colonization

In the 17th century, the French, English and Dutch established territories in North America, while Holland’s powerful navy allowed it to seize many of the Sp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 What is tourism?

- 2 Tourism as 'development'

- 3 Inside the tourist

- 4 Trouble in paradise

- 5 The new colonialism

- 6 Tourism as politics

- 7 New tourism

- Contacts

- Copyright