- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

No-Nonsense Guide to Green Politics

About this book

Climate chaos and pollution, deforestation and consumerism: the crisis facing human civilization is clear enough. But the response of politicians has been cowardly and inadequate, while environmental activists have tended to favour single-issue campaigns rather than electoral politics. The No-Nonsense Guide to Green Politics measures the rising tide of eco-activism and awareness and explains why this event heralds a new political era worldwide: in the near futurethere will be no other politics but green politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No-Nonsense Guide to Green Politics by Derek Wall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Sostenibilidad en los negocios. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781771130561Subtopic

Sostenibilidad en los negociosChapter 1

Global green politics

The term ‘green politics’ was once synonymous with the German Greens, who have participated in governments for much of the last three decades. But Green parties have now gone global – from Kenya to Mongolia, Taiwan to Brazil. And green political activity encompasses non-electoral campaigns and direct-action techniques the world over.

In 1983, 28 members of the German Green Party were elected to the West German parliament. Dressed informally in jeans, some of them brought in plants to place on their desks. Their colorful arrival contrasted with the suited members from the traditional parties.

Their success marked the first entry into a national parliament of a group of greens. The German Greens were elected in 1983 on a platform with four key elements: ecology, social justice, peace and grassroots democracy.

Green parties were born in the early 1970s, grew in the 1980s and green politics is now a global phenomenon. Green politics is first and foremost the politics of ecology; a campaign to preserve the planet from corporate greed, so we can act as good ancestors to future generations. However, green politics involves more than environmental concern.

Ecology may be the first pillar of green politics but it is not the only one. Andrew Dobson, an English Green Party member and academic, has argued that green politics is a distinct political ideology. While much ink has been spilt defining the term ‘ideology’, Dobson argues that it is a set of political ideas rather than a single idea, even one as powerful as concern for the environment. He argues that a political ideology provides a map of reality, which helps to show its adherents how to understand the world. He also believes that ideologies demand the transformation of society. He uses the term ‘ecologism’ to distinguish green politics from simple ‘environmentalism’.

The second pillar of green politics – social justice – is vital. Greens argue that environmental protection should not come at the expense of the poor or lead to inequality. This social justice element places greens on the left of the political spectrum. Greens argue, however, that the right-left spectrum is not the only dimension of politics, not least because there are many political parties that are committed to social justice but which fail to protect nature.

The third pillar – grassroots democracy – also distinguishes greens from many traditional socialists who have often promoted centralized governance of societies. This is a principle that greens share with anarchists and other libertarians. The demand for participatory democracy was one of the most important inspirations behind the German Greens. Greens during the 1980s made strong attempts to function in as decentralist and participatory a fashion as possible. Leaders were rejected, politics based on personality frowned upon and decisions made collectively. In the 21st century, Green parties are less radical but still pride themselves on allowing members to participate in policy and decision-making, even as democracy has gone out of fashion in many other political parties.

Nonviolence is the final pillar. Green parties evolved partly out of the peace movement and oppose war, the arms trade and solutions based on violence. Again, over time this commitment has become a little less clear-cut. The German Greens moved from being a radically anti-war party to participating in a government that sent German forces into Serbia. Greens have compromised over peace by supporting armed liberation movements such as the African National Congress, where they consider that strict nonviolence might lead to continued oppression. The German Greens under Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer were, however, leading opponents of the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Green politics does not stop with Green parties; the green movement as a whole is much larger. For example, green direct action networks such as Earth First!, Reclaim the Streets and Climate Camp have emerged in recent decades. These green direct-action networks focus on environmental issues but also promote the other pillars of green politics such as grassroots democracy, nonviolence and opposition to social injustice. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth have, meanwhile, a more ambiguous relationship with green politics. As environmental pressure groups, they lack party political ambition and ideology. Yet they have often worked with more radical direct-action networks and Green parties to achieve political change. Greenpeace has also combined the anti-war and environmental elements of green politics. Many environmental NGOs combine environment concern with promoting social justice and grassroots democracy.

The green movement is a little like an iceberg, with some highly visible Green parties, direct-action groups and radical NGOs looming large above looser and less visible networks of those who practice green lifestyles or contribute more sporadically to political change.

Green history

The origins of green politics are normally traced to the late 1960s and early 1970s. The first ecological political party – Australia’s United Tasmania Group – was formed in March 1972 to campaign against a big dam and to preserve the rainforests. Although they received a modest three per cent in state elections and failed in their goal of preserving Lake Pedder, they inspired the creation of Green parties all over the world. Their charter, a kind of manifesto, noted that they were:

- United in a global movement for survival;

- Concerned for the dignity of humanity and the value of cultural heritage while rejecting any view of humans which gives them the right to exploit all of nature;

- Moved by the need for a new ethic, which unites humans with nature to prevent the collapse of life support systems of the earth.1

A few weeks after the launch of the United Tasmania Group, a New Zealand/Aotearoa party called Values was formed at a meeting at Victoria University in Wellington. The Party had strong zero growth, gay rights and drug reform policies. It was the first party in New Zealand/Aotearoa to have a woman leader and an openly gay election candidate. However, in the 1970s, before the introduction of proportional representation, Values found it difficult to make an electoral impact and faded. It did, however, help to keep the country nuclear free and laid the foundations for the present Green Party, which is one of the strongest in the world.

Values and the United Tasmania Group were inspired by reports such as Limits to Growth and Blueprint for Survival, which argued that humanity was threatening vital ecosystems and depleting resources. Limits to Growth was produced by a team of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and used computer models to argue that, unless growth ceased, ecological catastrophe would result. The oil crisis of 1973 made such ideas fashionable. Blueprint for Survival, based on similar assumptions, was published in Britain by The Ecologist magazine, creating a huge public debate.

On 6 December 1973, The Guardian reported the birth of a new British party known simply as PEOPLE. Its manifesto stated boldly that it sought ‘a transition to a stable society in which people and places matter, which recognizes that the Earth’s resources are limited and that we must learn to live as part of nature, not as its master’. PEOPLE became the Ecology Party in 1975 and changed its name again to the Green Party in 1985. Today, it has two Members of the European Parliament, two members of the Greater London Assembly and over a hundred local councilors. The Scottish Green Party currently has two members of the Scottish Parliament.

The German and French Greens were also influenced by an anti-growth agenda. A Christian Democrat member of the West German Parliament, Herbert Gruhl, left his centre-right party to sit as an ecologist in the Bundestag. The French Ecologist presidential candidate René Dumont stressed the no growth agenda in his 1974 election campaign. However, in France and Germany, together with other western European countries, the Greens grew largely out of the movements against nuclear power in the 1970s.

The German Greens, in particular, saw themselves as the electoral wing of a wider protest movement. In fact, they contested elections into the 1980s as a list of candidates rather than as a formal political party, reflecting their social movement connections. The German extra-parliamentary left, which exploded on to the scene in the late 1960s and early 1970s, provided the German Greens with most of their initial key activists, including future Party leader Fischer. The events of Paris in 1968 – where the student demonstrators coined slogans attacking a society obsessed with shopping, such as ‘Down with the consumer society, the more you consume, the less you are’ – also fed into later developments in green politics.

The counterculture of the 1960s also fed into green party politics and the wider green movement. The counterculture drew on radical thinkers such as Herbert Marcuse and Erich Fromm from the Frankfurt School. They condemned capitalism not just because it exploited workers but also because it dehumanized us as passive consumers and polluted the environment. Counterculture thinkers of a different ilk, such as Aldous Huxley and Hermann Hesse, also influenced the nascent green politics. Huxley’s last novel, the utopia Island, provides a green blueprint for many aspects of society, including education, spirituality and the family. Charles Reich’s The Greening of America and Theodore Roszak’s Where the Wasteland Ends were also important to the emerging green movement.

While the 1960s counterculture and the 1970s scientific challenge to a growth economy were vital parts of the mix, green politics can be seen as having deeper roots. Peter Gould’s book Early Green Politics argues that the most ‘important period of green politics before 1980 lay between 1880 and 1900’.2 During this period the socialist, writer and artist William Morris drew upon the romantic ideas of John Ruskin to promote a political agenda that opposed industrial pollution and promoted conservation. Morris, politically active in opposing the Crimean War, also established a group to conserve churches. He became interested in Marxism, joined the Social Democratic Federation, Britain’s first socialist political party, along with Friedrich Engels and Marx’s daughter, Eleanor. Morris worked tirelessly to promote his own version of ecosocialism and wrote a utopian novel – News from Nowhere – promoting a green alternative. Gould argues that he was part of a much wider network of socialists and anarchists who shared virtually all the values of the modern green movement. Another prominent early green political activist was Edward Carpenter, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An openly gay man, an advocate of feminism and animal rights, he lived in near self-sufficiency with his partner George Merrill and founded the Sheffield Socialist Society. He believed that ‘The vast majority of mankind (sic) must live in direct contact with nature.’3

Even earlier examples of green politics can be found: the left-wing English Romantic poets such as William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley, along with Mary Shelley, come to mind. Indeed the novelist EM Forster described Carpenter as practicing the ‘socialism of Shelley and Blake’. Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein is an early piece of eco-literature, critiquing a science that manipulates nature with destructive results and creates a sad monster. The French philosopher Rousseau can, meanwhile, be seen as an early or proto-green who advocated a closer human connection to nature. While global environmental threats from nuclear weapons testing in the 1960s to climate change more recently has led to the growth of green politics, environmental problems have a long history. Indeed, laws against air pollution were enacted in Britain as early as the 13th century.

Green parties go global

Green parties are now a global phenomenon. The most successful African Green party has been the Mazingira Green Party of Kenya – mazingira is the Swahili word for ‘environment’. Mazingira’s 1997 presidential candidate Wangari Maathai also founded the Green Belt Movement, which encouraged tree planting as a conservation measure. She won a Nobel Prize for her work promoting peace and environmental justice. In 2009 the global federation of Green parties contained 19 members from African countries.

Greens have been elected in Benin and Senegal. There have been several attempts to create Green parties in South Africa, and most recently the Ecopeace Party and a variety of socialist groups based in Soweto have come together to found the Socialist Green Coalition. A Green Party candidate in Burkina Faso received seven per cent of the vote in the 1998 presidential election, while the former left-wing President Thomas Sankara – sadly assassinated – was a keen exponent of environmental policies such as community tree planting.

There are also a number of Green parties in Central and Latin America. The most successful by far has been the Brazilian Green Party (PV). The musician Gilberto Gil, a party member, acted as Minister of Culture in the coalition government. The former Environment Minister Marina Silva is to run as the Green Presidential candidate. Silva, who comes from a family of rubber tappers, has been a passionate defender of the Amazon. The Green Party of Chile is also well established but has not yet managed to elect parliamentarians. In much of Latin America left-leaning governments have become aware of environmental issues and green NGOs have emerged. The contribution of indigenous groups to green politics is particularly important in Latin America. Many Latin American Green parties have a skeletal organization and may represent little more than small groups of individuals with access to websites.

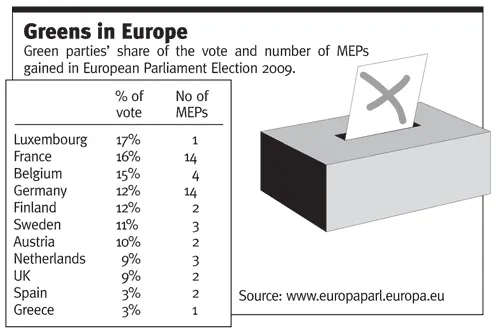

Green parties are relatively weak in North America as well – there are no Green representatives in the US Congress or the Canadian Parliament. One of the key factors affecting Green parties’ electoral success there has been the voting system. Green parties in much of Europe have gained some success because of proportional representation (PR). While PR systems vary, they typically guarantee that, if a political party gains 10 per cent of votes in a national election, it will gain 10 per cent of seats in parliament. Like the UK, Canada and the US have a ‘first-past-the post’ system, which explains the absence of nationally elected Greens in all three countries – though as this book goes to press the Green Party of England and Wales is confident that it will achieve an historic breakthrough by winning at least one parliamentary seat in the 2010 General Election.

In the US, the highest office achieved by greens so far is that of Mayor. US greens started organizing in the 1980s with a radical decentralist model inspired by the German Greens, as activists established Committees of Correspondence – a reference to revolutionary organization in the 18th-century war of independence against Britain. The Citizens Party, headed by the ecologist Barry Commoner, stood on an essentially green election platform during the 1980s before dissolving. In 1996, the consumer activist Ralph Nader stood as the Green Presidential candidate together with the indigenous activist Winona LaDuke. In 2000, Nader gained three per cent of the national presidential vote but his success led to bitter controversy as Democrats argued that his votes had prevented their candidate Al Gore from beating George W Bush. In 2008 the former US congress member Cynthia McKinney ran for President, together with hip hop artist Rosa Clements. The number of votes gained was modest but the campaign helped to build the party, which held to a platform of 10 key green demands. McKinney has been highly active in promoting conservation and civil rights, and in opposing both nuclear power and Israeli treatment of Palestinians.

The Green Party in Canada was preceded by a group called the Small Party, inspired by EF Schumacher’s book on green economics Small Is Beautiful. The Party is currently led by Elizabeth May, who is one of Canada’s most famous environmentalists. It is proud of its ‘neither right nor left’ orientation and has shifted from its decentralist and somewhat anarchic roots. Despite much favorable media attention, it has found it difficult to elect members to either the national or state legislatures. There are strong environmental direct action groups and indigenous networks in Canada, currently campaigning against exploitation of the highly polluting tar sands in Alberta.

Green politics in the Middle East

There are a very small number of Green parties in the Middle East. Some, like the Green Party of Saudi Arabia, are underground organizations comprising little more than a website and a few committed individuals. The long-standing Egyptian Green Party typically finds it difficult to progress in a country where democratic participation is limited.

Israel, however, contains two such parties, the new and more radical Green Movement and the Green Party, which has been closer to the Israeli state. There is also a Green Leaf Party committed to cannabis legislation. None have elected parliamentarians, although the Green Party has elected local officials.

The Green Movement narrowly failed to elect members of the Knesset in the 2009 election. It supports a two-state solution to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, and campaigns strongly on civil liberties and tolerance to religious difference. It believes that energy consumption in the country should be cut by 25 per cent.

However, green politics is probably best represented by the left party Hadesh. Dov Khenin from Hadesh is co-coordinator of a network of Israeli environmental groups, a member of the Knesset and came second in the 2008 Tel Aviv mayoral election with 34 per cent. Hadesh has opposed Israel’s attacks on Gaza and the Lebanon and supports the creation of a Palestinian state.

The Lebanese Green Party, one of the world’s newest, campaigns with the slogan ‘The earth knows no religion’ in a country where most parties have Shi’a, Sunni or Christian affiliations. As well as the pursuit of peace, a particular concern is forest conservation: their chair Christopher Skeff observed that ‘5,000 years ago a squirrel could travel the whole country by merely hopping from tree to tree’. He also noted: ‘I cannot pretend that Lebanese people wi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Global green politics

- 2. The overheating earth

- 3. Green philosophy

- 4. Need not greed

- 5. Politics for life

- 6. Strategies for survival

- Bibliography

- Copyright