![]()

FIRST PART

THE COMPANY:

A HUMAN ORGANIZATION

CHAPTER 1

BUSINESS ORGANIZATIONS AS HUMAN REALITIES

Introduction

A business firm is a human organization, composed of persons who work with some kind of coordination to achieve certain goals or results. In fact, all human organizations are no more than this: groups of people who coordinate their actions to achieve goals that everyone has an interest in achieving, although this interest may be due to very different motives.

Business organizations thus resemble families, sports clubs, city councils, the army and many other organizations precisely in the fact that they are all human organizations. Of course, all these organizations, and others that we might have mentioned, also include many aspects that distinguish them from each other.

Perhaps the most obvious way to define what distinguishes them is to look at what it is that each of them normally does. Thus, it would be reasonable to say: “I acknowledge that a business is just as much a human organization as a club where a few friends meet to play chess, but it doesn't seem to me that what they have in common-being human organizations— is more important than what makes them different—manufacturing, buying and selling something on the one hand, playing chess on the other”.

No doubt someone could point out that what is important is not this difference in what they do. after all, a business could be created whose aim was to operate a social club where people could go to play chess. The important thing is that in a business all these things— manufacturing and selling cars, or running a club for chess players—are done for a different reason than the club run by a group of friends: a business seeks to earn money; friends only seek to have fun.

Viewed from this perspective, an organization composed of a group of friends who want to have fun building cars will more closely resemble the organization formed by another group of friends to play chess than the latter would resemble a chess club run as a business, or the former a car manufacturer.

In fact, we could go on multiplying perspectives in order to define differences between various types of human organizations. No doubt, for a particular case, we would find that a particular perspective provides useful insights to account for differences which, in that particular case, are very important; but that same perspective might have little bearing on many other cases.

The aim of scientific analysis is to explain in an orderly manner the various aspects which determine whether something is or is not a particular kind of thing. Therefore, one begins by studying very general aspects or properties and then goes on to consider others which define more particular cases.

Thus, if we say that businesses are human organizations, then everything that can be said in general terms about human organizations will also be applicable to them. Of course, there will be other things that are only applicable to businesses (a particular kind of human organization) and not to other kinds of organizations.

When the human side of a business is not working smoothly, the fault should not be sought in those other aspects of the business that make it a particular type of organization, such as its size, type of activity or the nature of its production and distribution processes. For this reason, the analysis of businesses as human organizations will be very useful, since it is this analysis that seeks to explain the influence of what is happening to the human side of a business organization on the behavior of the enterprise as a whole.

What is an organization?

We have already said that a human organization is a group of people whose efforts— actions—are coordinated to achieve a certain objective in which everybody has an interest, although their interests may be due to very different factors.

For an organization to exist, the mere existence of a group of people is not sufficient; it is not even sufficient that they all have a common purpose. The truly decisive factor is that these people organize themselves—coordinate their activity—by ordering joint action towards the achievement of certain results which, although perhaps for different reasons, they all consider it in their interest to achieve.

For example: the group of people on a street at a particular moment is a well-defined group—a set of specific persons—, but they do not constitute an organization. It is even likely that at least some of these people have a common purpose: to get to the other side of the city as quickly as possible. But this does not suffice for them to be considered an organization. However, if, while waiting for the bus, they start to talk about their problem and decide to share a taxi so as to avoid a wait and arrive at their destination sooner, they have now organized themselves: they will be an organization, even if only for a short period of time (as long as their cooperation lasts).

It is true that when we speak of human organizations, we are not usually referring to such ephemeral phenomena as the one just described: we usually have in mind something stable and lasting, such as families, businesses, town councils or sports clubs. Our common sense tells us-and rightly so—that for an organization to be stable and to last for a long period of time it requires certain mechanisms and the interplay of certain forces not present in ephemeral organizations, in which a group of people agree to solve a problem that affects them, their cooperation ceasing to exist once it has been solved.

However, the essential elements of an organization are already present even in these ephemeral organizations, in the same way that the basic elements of a large city are already to be found in a small village. These basic elements are: human actions, human needs and a formula or means of coordinating actions to satisfy needs. On this simple basis, we can already make an important distinction that is valid for any organization: the distinction between the formal organization and the real organization.

Formal organization and real organization

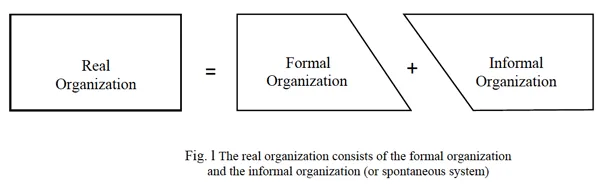

A formal organization is a formula for coordinating actions that can help to satisfy needs. The real organization is that which exists when a particular group of people decides to implement a formal organization.

The real organization includes the formal organization plus the entire set of interactions that occur between people, which, logically, are not foreseen—and, in many cases, not foreseeable—in the formal organization. The real interactions that occur within a real organization, and which are not considered in the formal organization, are termed informal organization, spontaneous organization or system and non-formalized system. (Fig. 1)

What happens in the world of non-formalized relations or interactions is of decisive importance for the life of the real organization. Something similar happens with the stars observed by astronomers: the most frequently observed phenomena are the superficial ones. But those which make whole stars vanish, releasing incredible amounts of energy, take place within the core of these heavenly bodies. The most visible and immediate aspect of a real organization is its formal organization. This is what is explained to us when we ask what an organization does, and why. However, its basic processes are to be found on a deeper level, which is determined by informal interactions, and on which the real organization depends for its future. In the following pages we will discuss in somewhat greater detail what the formal organization consists of, as well as the basic processes which ensure its existence as a real organization.

Elements of the formal organization

We have already said that the formal organization (the form in which the interactions within a real organization are explicitly organized) is only a formula, or means of coordinating actions, in order to achieve results which may help to satisfy human needs. This formula has at least two components:

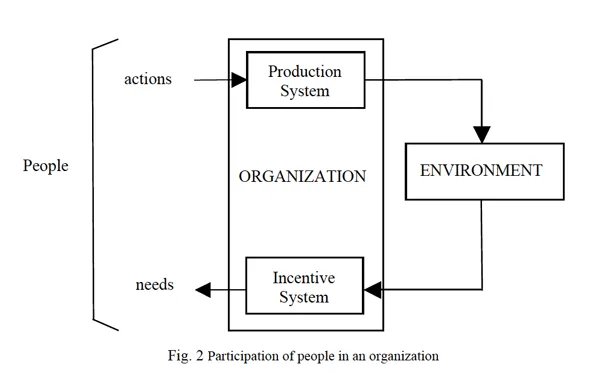

a) Production system or production rules: these define the actions to be performed by those persons who are participants in the organization so that it may operate and achieve its purpose.

b) Incentive system or incentive rules: these define what these persons will receive in return for being members.

Anybody who participates in an organization contributes something and receives something in return for his involvement (although there may be cases in which a person only contributes or only receives). What a particular person contributes depends on his role in the production system; what a person receives depends on his role in the incentive system. The production system is that body of rules which governs the actions of individuals in order to achieve the desired results for the organization. The incentive system is that body of rules through which the benefits gained by these results are distributed among the organization's members.

Fig. 2 shows why, in many cases, an organization may be defined as a means by which individuals act upon their environment in order to achieve results which would not be achievable without the joint effort coordinated by the organization.

We have already seen that a formal organization is only a theoretical possibility. For this organization to actually exist, there must be people who want to and are capable of organizing themselves in this fashion. Before speaking of real organizations, however, it should be noted that a formal organization cannot be formed by just any pair of production and incentive systems. If the production system is unable to produce whatever is necessary for the incentive system to be applied, a formal organization defined by both systems would not be possible: it would be a theoretical nullity.

Very similar to this “impossible organization” are the utopian organizations which, in order to operate, require people or an environment which does not exist in reality. A large number of the “solutions” that are generally proposed to serious problems by a group of friends chatting about them could be categorized as utopian organizations.

We mention these extreme cases because they may help us gain insight into one aspect of a good understanding of real organizations; those which exist and are in operation, or those that may appear in reality at any time.

This aspect is the following: it is not enough merely to be possible (i.e., not contradictory or utopian) for a particular organization to actually exist. In order for an organization to exist and operate, three basic factors are required:

1. The formulation of certain goals or results which may be effectively achieved by implementing the production system, and whose achievement would enable the incentive

system to be implemented so that people will be satisfied:so that they actually receive what they expect from the organization.

2. That the people acting in the organization can do what the production system requires them to do.

3. That they actually want to do what the production system requires them to do.

These three points summarize what are considered to be the basic functions or tasks of an organization's managers: the body that governs an organization. Although they can be defined in a number of ways, they are usually given the following names:

1. Operational definition of purpose, which specifies the results to be achieved by the organization and how the organization's members must act in order to achieve them.

2. Structuring the definition of purpose: that is, finding the persons who can perform the different tasks specified by the operational definition and assigning the corresponding task to each of them.

3. Implementing the purpose: that is, making sure that each organization member is actually motivated to perform ...