![]()

1. Chronology of the Mid Upper Palaeolithic of European Russia: Problems and prospects

Natasha Reynolds

Abstract

The archaeological record of the Mid Upper Palaeolithic (MUP) of Russia (c. 30,000–20,000 14C years BP) is important both intrinsically and as part of a wider European archaeological landscape. Numerous issues have meant that the archaeology has not received the attention it deserves in the West, and it is not currently possible to easily synthesise information on Russian sites with that from elsewhere in Europe. One of the biggest problems for making sense of the archaeology is that of chronology, as there is no consensus on a chronocultural scheme for this time period in Russia, and both absolute and relative dating of sites remains problematic. The archaeology of the sites of Kostenki 8 Layer 2 and Kostenki 4 are outlined to demonstrate the importance of these sites and to illustrate some of the problems that need to be overcome in order to determine an accurate chronology. There is great potential for future work to improve the understanding of these sites, and hence to illuminate broader archaeological debates related to the European MUP.

Introduction

The Upper Palaeolithic record of Russia, with its rich sites that have yielded huge lithic assemblages, dwelling-structures, mobiliary art, and burials, holds great interest for archaeologists worldwide. Its clear similarities to the contemporary archaeology of the rest of Europe mean that it is always included as part of the European Upper Palaeolithic when this is considered as a whole. However, the archaeology from this region remains relatively under-exposed in the West, and there are huge difficulties in synthesising archaeological evidence from across the continent. This has been bemoaned for many years but more than two decades after the collapse of the USSR, progress remains slow.

Geopolitical realities constituted a serious barrier to communication throughout most of the twentieth century. Although the Iron Curtain has fallen, economic barriers to co-operation remain in place, and colleagues from all parts of Europe often find it difficult to attend conferences at distant parts of the continent. The language barrier still poses major difficulties, and although Russian archaeologists increasingly publish in English and French, the vast majority of primary literature is inaccessible to the non-Russophone. The persistent differences in intellectual traditions are, perhaps, less obvious. Soviet archaeological thought diverged strongly from Western traditions (Bulkin et al. 1982; Davis 1983; Vasil’ev 2008); post-Soviet Russian archaeological thought has inherited many of the particularities of the local tradition.

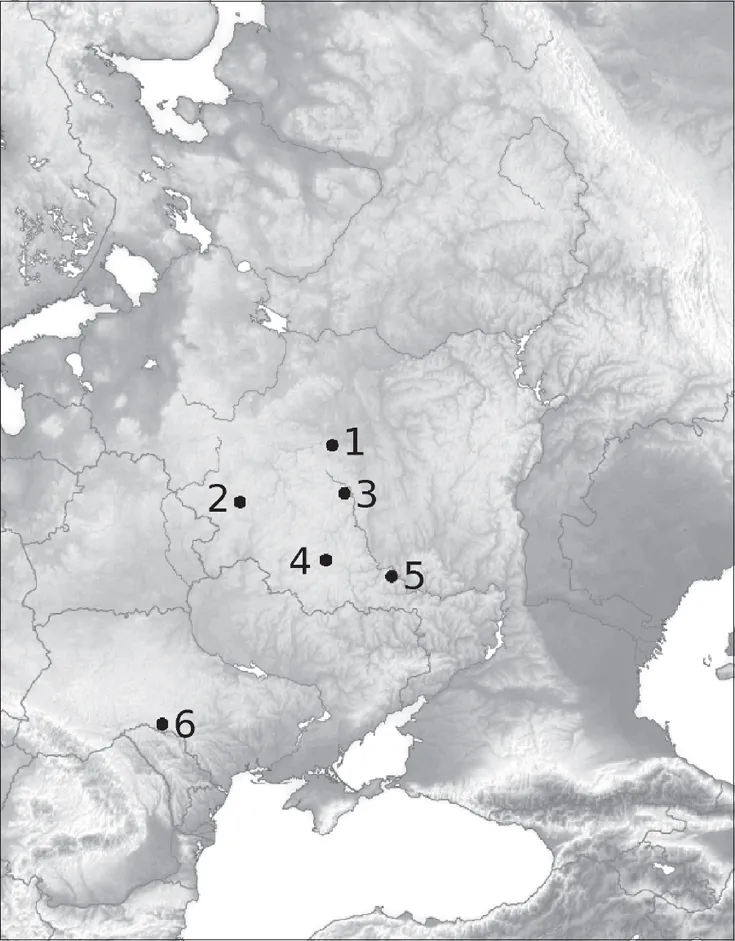

The Russian record is undoubtedly deserving of international publication and discussion. The mobiliary art and claimed existence of dwelling structures are well known worldwide; descriptions of the rest of the archaeology have had less dissemination. In combination with evidence from across Europe, the record offers an opportunity to gain an understanding of pan-European cultural processes during the Mid Upper Palaeolithic (MUP). The present article attempts to give a review of the current state of affairs in the study of this region from a western European standpoint, and to outline two major Russian MUP sites. Locations of sites discussed in the text can be found in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Some sites and regions mentioned in the text: 1. Zaraysk; 2. Khotylevo-2; 3. Gagarino; 4. Avdeevo; 5. The Kostenki-Borshchevo area; 6. Molodova-5.

The European MUP

The European MUP, frequently treated as synonymous with the Gravettian, dates from approximately 30,000 to 20,000 14C years BP. The period has been described as a “Golden Age” (Roebroeks et al. 2000) and has provided archaeological evidence for a broad spectrum of human activity, including textile production, ceramic production, processing of plant resources, and, more controversially, dog domestication (e.g Aranguren et al. 2007; Germonpré et al. 2012; Revedin et al. 2010; Soffer 2004; Vandiver et al. 1989).

The traditional type-fossils of the Gravette point and backed bladelet are found widely and in large numbers throughout this period; however, a great deal of temporal and regional variation is known among Gravettian industries. Industries such as the Maisierian/Fontirobertian, Pavlovian, and Noaillian, which date to this time period, are idiosyncratic and geographically and chronologically restricted, and demonstrate the technological diversity of the European MUP. They are usually (but not always) treated as sub-types within a larger Gravettian cultural and technological entity. The term ‘Gravettian’ is itself ambiguous, and may be used to describe a technocomplex or group of technocomplexes, a time period, or a perceived cultural grouping – a state of affairs which reflects the historical development of the term, as well as the perhaps under theorised nature of its usage (de la Peña Alonso 2012).

In recent years, great progress has been made in improving our chronology of, and understanding of the variability within, the Gravettian. Excellent work has been carried out on Western European lithic assemblages, often incorporating intra- and inter-site comparison (e.g. Borgia 2009; Klaric 2007; Pesesse 2006; Wierer 2013). Technological studies, for example on methods of bladelet production, are proving to be especially productive. Much attention has also been concentrated on the earliest Gravettian and the timing and nature of the Aurignacian/Gravettian boundary, with various claims across Europe for Gravettian assemblages earlier than 30,000 14C years BP (Conard and Moreau 2004; Haesaerts et al. 1996; Prat et al. 2011). The relationship between the Aurignacian and the Gravettian, if any, continues to be debated on the basis of evidence from various areas across Europe (Borgia et al. 2011; Kozłowski 2008; Moreau 2011; Pesesse 2008, 2010). Recent projects seeking to improve the radiocarbon chronology of the Upper Palaeolithic have dramatically improved our chronological framework for this time period (Higham et al. 2011, Jacobi et al. 2010).

The MUP archaeology of Russia and the Kostenki-Borschevo region

In contrast with the rest of Europe, the Mid Upper Palaeolithic of Russia is far from synonymous with the Gravettian. Rather, it is widely held that several other industries were also extant during the MUP, sometimes overlapping in time within a very small geographical region. The Gorodtsovian, Gravettian, Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture and Epigravettian are widely described (Sinitsyn 2010); other phenomena such as the “Epi-Aurignacian” (Anikovich 2005a) are also sometimes included in the Russian MUP. The majority of the evidence for the MUP of European Russia derives from the famous Kostenki-Borshchevo region, near the city of Voronezh, where twenty-six Upper Palaeolithic sites have been identified.

The Kostenki-Borshchevo sequence

The sites of the Kostenki-Borshchevo area are found along the right bank of the Don River and within a series of ravines, which open onto the river, along a distance of perhaps seven kilometres. Several river terraces have been identified above the floodplain and extend into the ravines; the Palaeolithic cultural layers were found within deposits on the first and second terraces.

On the second terrace, a series of humic layers, loessic layers, and a visible tephra deposit were found. The sequence from the base consists of a Lower Humic Bed overlain by loessic deposits and a tephra layer. These are in turn covered by an Upper Humic Bed, followed by further loessic deposits and a thinner humic layer known as the Gmelin soil, which is sealed by another series of loessic deposits, believed to date to the Last Glacial Maximum (Holliday et al. 2007). Rogachev (1957), working in the 1950s, used this stratigraphy to create a basic tripartite chronological grouping for the sites, which remains in use to this day: 1) Lower Humic Bed sites, 2) Upper Humic Bed sites, 3) sites from above the Upper Humic Bed. On the first terrace, the stratigraphy is more limited, containing only loessic deposits and the Gmelin soil. Therefore, all sites from this terrace are attributed to Rogachev’s third chronological group.

Chronostratigraphy and palaeoclimatic correlation

The part of the Kostenki geological sequence relating to the MUP (i.e. the Upper Humic Bed and above) has yet to yield precise, accurate and consistent absolute dates. However, the tephra deposit between the Upper and Lower Humic Beds has been securely identified as the Campanian Ignimbrite, dated to approximately 40,000 calendar years ago (Fedele et al. 2008; Giaccio et al. 2008; Hoffecker et al. 2008; Pyle et al. 2006; Sinitsyn 2003). At least three individual palaeosols have been identified within the Upper Humic Bed (Sedov et al. 2010). By comparison with well-studied sedimentological sections at Kurtak (Russia), Mitoc-Malu Galben (Romania) and Molodova (Ukraine) (Haesaerts et al. 2010), it is possible to suggest a tentative correlation between the Upper Humic Bed and Greenland Interstadials 8–5, and between the Gmelin soil and one, or both, of Greenland Interstadials 4 and 3. This correlation, however, is based purely on published descriptions and awaits publication of a systematic study and dating of the chronostratigraphy. Correlations between the Upper Humic Bed and the Bryansk soil (Sedov et al. 2010), and the Bryansk soil and Greenland Interstadial 8 (Simakova 2006) have previously been suggested.

Russian MUP industries

The Gravettian of Russia is defined by the presence of Gravette points/microgravettes and backed bladelets, in layers of the expected age (c. 30,000–20,000 14C years BP). The Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture, importantly, is generally treated separately, despite the presence of backed bladelets and Gravette points in sites of that industry (Gavrilov 2008; Lisitsyn 1998; Tarasov 1979). Perhaps six Kostenki sites (Kostenki 8 Layer 2, Kostenki 4 Layers 1 and 2, Kostenki 9, Borshchevo 5, Kostenki 21 Layer 3, Kostenki 11 Layer 2) relate to the Gravettian excluding the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture (Sinitsyn 2007). Kostenki 8 Layer 2, discussed in detail below, is found in the Upper Humic Bed and has yielded a relatively early radiocarbon date of 27,700 ± 700 14C BP (GrN-10509); the other sites are all found above the Upper Humic Bed and hence belong to Rogachev’s third chronological group. Sinitsyn (2007) argues that the sites other than Kostenki 8 Layer 2 represent four faciés of the Recent Gravettian, which co-existed at Kostenki alongside the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture. All the sites have yielded sizeable numbers of backed bladelets. Radiocarbon dates for sites other than Kostenki 8 Layer 2 range widely; however, Sinitsyn (2007), following earlier work, dates the third chronological group to 27,000 to 20,000 14C years BP.

The Gorodtsovian industry is unique to Eastern Europe and, perhaps, to the Kostenki region. The type-site for the industry is Kostenki 15 (Gorodtsovskaya), found within the Upper Humic Bed (and hence belonging to Rogachev’s second chronological group). Unusually, the type-fossil for this industry is not lithic but osseous: a number of remarkable bone “shovels” were discovered at Kostenki 15 (Rogachev 1957). The lithic assemblage from this site is relatively small, numbering about 350 retouched flint and quartzite pieces among a total collection of more than 2000 lithics. The collection includes large numbers of retouched blades and scrapers made on blade blanks, splintered pieces, and retouched flakes but, notably, no bladelets (Klein 1969; Sinitsyn 2010). There is no clear consensus on which other Kostenki sites should be attributed to the Gorodtsovian; Kostenki 14 Layer 2, Kostenki 12 Layer 1 and Kostenki 16 are often included, but there is substantial variation between researchers (Rogachev and Sinitsyn 1982; Sinitsyn 2010). The site of Talitsky in the Urals is sometimes included, and recently an assemblage from the site of Mira (Ukraine) has been attributed to it (Sinitsyn 2010; Stepanchuk et al. 1998). The available radiocarbon dates for Kostenki 15 are as follows: 25,700 ± 250 14C years BP (GIN-8020) (Chabai 2003); 21,720 ± 570 14C years BP (LE-1430) (which is inconsistent with the site’s stratigraphic position, see Rogachev and Sinitsyn 1982). Some AMS radiocarbon dates for Kostenki 14 Layer 2 range between 29,240 ± 330 (GrA-13312) and 26,700 ± 190 (GrA-10945) 14C years BP (Holliday et al. 2007). These ages overlap not only with the Gravettian elsewhere in Europe but also with the Gravettian as represented at Kostenki 8 Layer 2. It has been suggested that the Gorodtsovian sites do not represent a cultural grouping, but, rather, are a reflection of site function including kill-butchery events (Hoffecker 2011).

The Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture is found more widely than the earlier Gravettian, including at Kostenki (Kostenki 1 Layer 1, Kostenki 14 Layer 1, and Kostenki 18), Avdeevo, Zaraysk, and (more problematically) Khotylevo-2 and Gagarino (Sinitsyn 2007). Similarities with sites beyond European Russia are often stressed, as demonstrated by the technocomplex’s frequent inclusion in larger units (e.g. the Willendorf-Pavlov-Kostenki-Avdeevo cultural unity or the ‘shouldered-point horizon’ of Eastern Europe (Grigor’ev 1993; Otte and Noiret 2003; Svoboda 2007). The technocomplex is defined according to the presence of shouldered points and Kostenki knives in the lithic assemblage, female (‘Venus’) figurines, and long lines of hearths, surrounded by pits and oriented north-west to southeast. These latter features are generally interpreted as the remains of domestic structures. The majority of frequently cited dates for these sites fall between 24,000 and 21,000 14C years BP (Amirkhanov 2009; Anikovich 2005b; Gavrilov 2008; Sinitsyn 2007); at Kostenki, all relevant cultural layers are found above the Upper Humic Bed, i.e. in Rogachev’s third chronological group. The Epigravettian, not discussed here, is also represented by multiple sites at Kostenki.

Dating of assemblages

The tripartite scheme of Rogachev is certainly useful for a general relative chronology. However, the lengths of time included in each part of the scheme (probably up to ten millennia) means that it is a very low-resolution chronology. Within the second chronological group (found within the Upper Humic Bed), Aurignacian, Gravettian, Gorodtsovian and Streletskayan assemblages are all found; the third chronological group includes Gravettian, Gorodtsovian, Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture and Epigravettian assemblages (Sinitsyn 2007). Some consensus has emerged on the stratigraphical relationships, and hence chronological relationships, between these industries (e.g. the Epigravettian is later than the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture)....