![]()

Chapter One

The beginning of Jewish history

The origins of biblical patriarchs

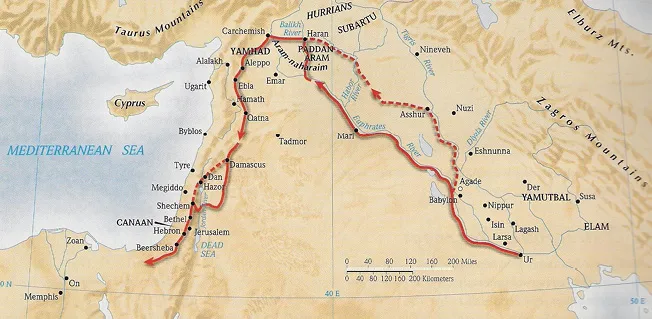

Jewish history begins with the biblical patriarch Abraham who lived in Ur, one of the most ancient cities of the world, in legendary Sumer. At the time, he was called by the slightly simpler-sounding name of ‘Abram’. The Bible does not say how long Abram lived in Ur; however, it does make clear that neither Ur nor southern Mesopotamia as a whole were the patriarch’s native land. His family had come from an entirely different area, the region of Haran, which is very far away in northwestern Mesopotamia. But Sumer was not fated to become Abram’s new homeland. Maybe there was not enough unoccupied pastureland for the West Semitic nomads or perhaps conflicts arose with the local rulers; we shall probably never know the truth. But in any case the head of the family, Abram’s father, Terah, decided to set off for the land of Canaan. But Mesopotamia and Canaan were separated by the vast Syrian Desert, which became traversable only an entire millennium after Abram’s death, when the “desert ship” – the camel – was domesticated. In Abram’s time, the main beast of burden was the donkey and for this reason even the hereditary nomads did not dare to venture far into the desert. At that time, the journey from Sumer to Canaan involved a round-about route through northwestern Mesopotamia and Haran, the area from which Abram’s family originally came. There, in their initial homeland, they were forced to delay their travel for a considerable time. Terah died and authority over the family passed to his eldest son, Abram. In fulfillment of his father’s wishes, Abram led his family to the southwest, through Syria and into Canaan. His first stopping place was in the central part of the country, in the area between Shechem in the north and Bethel in the south. But for some reason he did not remain in central Canaan, where water and fertile land were most abundant, but instead gradually pushed southwards, into the hottest and driest regions bordering the Negev Desert. Here, in the south, in the triangle formed by Hebron, Beersheba, and Gerar (near Gaza), Abram and his family lived as semi-nomads. This concluded the Jewish patriarch’s first period of traveling. It is a time that raises many questions.

In religious literature, the decision to migrate to Canaan has traditionally been attributed to Abram and has been linked with his new, monotheistic faith. In truth, the fateful decision to leave Ur to go to Canaan was made not by Abram, but by his father, Terah, who did not worship the one God and had no personal relationship with Him. The Bible makes this completely clear: “Terah took his son Abram, his grandson Lot son of Haran, and his daughter-in-law Sarai, the wife of his son Abram, and together they set out from Ur of the Chaldeans to go to Canaan. But when they came to Haran, they settled there” (Genesis 11:31). Thus it was not Abram who took his family, but Terah. And it could not have been otherwise: according to the laws and traditions of the time, Abram’s father, as the senior member of the family, was the one who was supposed to make decisions while the rest of his family was required to obey him. But why was Canaan chosen as the destination? After all, it was not close, being located a long way from both Ur and southern Mesopotamia in general; in fact, one could say that it lay at the other end of the ancient Near East. How could Terah have known that his family and tribe would find unoccupied land and available water there? All of these questions have one answer: Terah had received exhaustive information from his kinsmen who had already settled in Canaan. These kinsmen were Western Semites, just as he was, and had already left their common homeland in northwestern Mesopotamia; however, unlike Terah and his family, they had gone not to Sumer, but to Canaan. The journey across such large distances and with such a large quantity of livestock involved many difficulties and much risk. The decision to set out could only have been taken upon knowing that the family would find a place and security in this new land. And Terah likely did receive such guarantees: it is significant that, following his father’s death, Abram set out not for Canaan in general, but for the southern part of the country specifically. The Bible itself says nothing of the reasons for departing for Canaan, confining itself to reference to God’s will: “The Lord had said to Abram, ‘Leave your country, your people and your father’s household and go to the land I will show you’” (Genesis 12:1). However, the land for which Abram was heading was not unoccupied; the Bible reminds us that, “At that time the Canaanites were in the land” (Genesis 12:6). Having been the first of the Western Semites to arrive in Canaan, the Canaanites were in Abram’s time a settled agricultural people. A later wave of Western Semites, the Amorites, had also settled nearby. They had already occupied the best areas of the land that was vacant, in north and central Canaan; in the arid south, however, there still remained large areas of unoccupied pastureland. By agreement among the West Semitic nomads, this southern part was given to Abram and his people. In those times, of course, southern Canaan was more pleasant than it is today. Above all, the Dead Sea had not yet formed. In its place was the Jordan River Valley, of which the Bible says: “the whole plain of the Jordan was well watered, like the garden of the Lord, like the land of Egypt, toward Zoar. (This was before the Lord destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah)” (Genesis 13:10). According to the Bible, the land that became the bottom of the Dead Sea was previously called the Valley of Siddim (Genesis 14:3) and the Jordan River supplied it with water in abundance. Later, seismic processes resulted in an ecological catastrophe: a significant part of the Jordan valley was transformed into a lifeless, salty sea; flourishing cities perished; and any survivors abandoned this disaster area. As time went on, the climate became increasingly arid and hostile to agriculture; southern Canaan gradually became the undisputed ancestral property of the West Semitic nomads.

In biblical literature, you may encounter the mistaken view that Abram’s monotheistic faith had already taken root before he came to Canaan, and that the Lord who prompted him to set out for a new homeland was the same God to whom Abram’s descendants prayed. However, the Bible makes no distinction between the god of Terah and the God of Abram. The break with the old deities in fact happened much later, when Abram was already in Canaan. In recent years, it has become common to hypothesize that Ur and Haran were both centers of worship of the god Sin (the moon-god) and that Abram’s family were priests in this cult. Certainly, the Moon cult was popular in both cities, but this by no means implies that members of the patriarch’s family were priests in the cult and left Ur for Haran because of this reason.

Wanderings of Abraham. 20th century B.C.E. Holman Bible Atlas.

Who was Abram in reality and to which people did he and his family belong? The names of the biblical family members and the time at which they appeared in Mesopotamia, Canaan, and later Egypt, are signs not only of their West Semitic origin, but also of the fact that they belonged to the Amorites or a related people. We have no information on the ethnic origins of Abram’s family up until his arrival in Canaan. It is only in the episode involving the captivity of Lot, his nephew, that the Bible identifies the patriarch himself for the first time: “One who had escaped came and reported this to Abram the Hebrew [Ivri].” (Genesis 14:13). Today the word ‘Hebrew’ (Ivri) is translated from the biblical Hebrew as ‘Jew’. But 4000 years ago, this word had a different meaning and was pronounced differently – ‘Habiru’ or ‘Apiru’. It was the name for semi-nomadic, West Semitic people who did not have their own permanent tribal territory. Even if we assume that the Habiru were not actually Amorites, they were certainly their close relatives. To begin with, this term was more social than ethnic; it signified semi-nomads who were freshly arrived. From an ethnic and linguistic point of view, the Habiru hardly differed from the settled West Semitic peoples of Syria and Canaan who surrounded them. They all had common roots and the same origin; in terms of life style, however, there were important differences. The Habiru remained semi-nomads and did not settle on the land until the 12th century B.C.E. In Abram’s time, the Habiru were a large group of tribes scattered throughout Syria, Canaan, and Mesopotamia. They were to be found in all corners of the Semitic world of that time, but especially in Canaan and southern Syria, where they were a serious military and political power.

From the beginning of the 2nd millennium B.C.E., southern and central Canaan was already considered to be the land of the West Semitic semi-nomads. It is important to mention that when Joseph found himself in Egypt, he said of himself: “For I was forcibly carried off from the land of the Hebrews” (Genesis 40:15). Today this phrase means ‘from the land of the Jews’. But at the time it sounded and was understood differently, namely as ‘from the land of the Semitic semi-nomads’. The Habiru were warriors; dignitaries among the local rulers; artisans; and hired hands. But most lived a pastoral life, wandering nomadically with their herds over the entire territory of the Fertile Crescent. Relations between the Habiru and the settled agricultural population were very much reminiscent of the relations between Bedouin and fellahin (peasants) in Arab countries. Each side distrusted the other; however, periods of hostility alternated with peaceful and even friendly coexistence – and all the more so, since both sides needed to barter foodstuffs and goods. From the cultural point of view, the Habiru very quickly assimilated with the environment in which they lived, adopting the traditions, customs, religious beliefs, and professional skills of the local peoples. The Hebrews constituted only a small part of the Habiru who were in Canaan and southern Syria. As time went by, the term ‘Habiru’ increasingly took on an ethnic meaning and finally came to signify two groups of Hebrew tribes – the northern and southern. Thus Abram and his family were semi-nomadic Western Semites or Habiru.

Family or tribal group?

The Bible speaks only of Abram’s family; however, the episode describing the liberation of Abram’s nephew Lot makes clear that the patriarch was leading, at the very least, his entire tribe. “When Abram heard that his relative had been taken captive, he called out the 318 trained men born in his household and went in pursuit as far as Dan. During the night Abram divided his men to attack them and he routed them, pursuing them as far as Hobah, north of Damascus. He recovered all the goods and brought back his relative Lot and his possessions, together with the women and the other people” (Genesis 14:14-16). In order to assemble a force of 318 warriors, Abram’s family must have numbered at least 6000 - 7000, which made them not a clan, but a rather large tribe. Now according to estimates by archeologists, the entire population of Canaan at the time amounted to no more than 150,000 people. Given that, Abram’s tribe was a force of no small strength – and that is in spite of the fact that on the eve of these events, some of their number left to follow Lot to the east. In order to pursue the enemy from today’s Dead Sea to Damascus, you would have needed not just a large number of people, but also well-trained and experienced warriors. From the biblical narrative, it follows that the local Amorites – Aner, Eshkol, and Mamre – entered into an alliance with Abram. As a rule, families did not conclude alliances among themselves, so what we have here, evidently, is an alliance between the local Amorite rulers and Abram as the head of one of the Habiru tribes. Granted, one should treat the numbers given in the Bible, especially in its earliest texts, with utmost caution. And yet, even if the number 318 is for some reason unreliable, it still remains an eloquent fact that Abram and his allies were able to achieve the retreat of the entire coalition of southern Syrian rulers who had invaded Canaan. This testifies to the fact that Abram’s ‘family’ was in fact an entire semi-nomadic tribe or tribes – an alliance with whom would have been a desirable objective for many rulers in the southern part of the country.

At the very beginning of the biblical narrative concerning Abram’s stay in the land of Canaan, we encounter a new fact confirming the supposition that ‘Abram’s family’ was in fact not only a tribe, but a group of tribes:

The very description of the places where Lot settled – a region extending for more than 70 miles – is evidence that what we have here is not families, but tribes. Lot’s separation from Abram was only the first division among the numerous tribes of West Semitic nomads of Amorite origin who had come to southern Canaan. Those who went east with Lot came to be known as the ‘Sutu’ (‘Sutians’). Some scholars suppose that the ethnonym ‘Sutu’ derived from ‘Sutum’, the name for the biblical Sheth, son of the primogenitor Adam. Sheth was thought to be the ancestor of all the West Semitic nomadic tribes covering the area from Canaan to Mesopotamia. It is possible that ‘Habiru’ was established as the name for the Hebrews later, when they were already in Canaan, and that, when they lived in Mesopotamia and up until their arrival in Canaan, they had been known as Sutu. Be that as it may, those who remained with Abram to the west of the Jordan River became known as Habiru and those who left for the east of the Jordan River were called Sutu, even though during Abram’s time there was almost no difference between the former and the latter. However, the Habiru were even then drawn to the settled population and lived right in their midst, while the Sutu preserved a purely nomadic way of life. The Egyptians were very familiar with the nomadic Sutu and had their own name for them – ‘Shasu’. Later, the Sutu who lived in Transjordan experienced further divisions, with some of their number forming the origins of peoples, such as the Moabites and the Ammonites.

Adoption of the cult of El

Not only was Abram the leader of the group of Habiru tribes, but he was also their high priest. Upon his arrival in Canaan, he built sacrificial altars and conducted services at Elon-More near Shechem, at Bethel, and at Elonei Mamre near Hebron. “…‘You are a mighty prince [of God] among us,’” the Hittite men of Hebron told him” (Genesis 23:6). It was quite common in Canaan in those times for a leader to assume both functions (of supreme ruler and of high priest). The Bible tells of Melchizedek, king of the city of Shalem (Jerusalem), who was simultaneously a priest of the Almighty God (Genesis 14:18). Thus there was nothing surprising in Abram initiating the adoption of a new religious faith within his family and tribe. The famous covenant between Abram and the Lord was concluded in the tribal sanctuary of Elonei Mamre, in the region of Hebron:

The change of names and the rite of circumcision were signs not of the religious reform of an already existing cult, but of the adoption of a new faith and a union with a new God. At Elonei Mamre, a true revolution occurred in the religious beliefs of Abraham and his tribe. Abraham rejected the old gods whom he and his tribe had worshipped in both their homeland of Haran and in Ur. Their new homeland brought a new god – most likely, the supreme Canaanite god El. It is also possible that this was the cult of the Most High God (El Elyon), the lord of heaven and earth who ruled in the neighboring city of Shalem and whose king/high-priest, Melchizedek, was an ally of Abraham. It is interesting to compare how each called their god. Melchizedek “blessed Abraham, saying, ‘Blessed be Abraham by God Most High, Creator of heaven and earth’” (Genesis 14:19). However, Abraham turned to the king of Sodom and named his God: “But Abraham said to the king of Sodom, ‘I have raised my hand to the Lord, God Most High, Creator of heaven and earth…’” (Genesis 14:22). The similarity in the way that this god is characterized is striking. It is fair to assume that the similarity was not confined to external characteristics; it was also a matter of the nature of the religious cult itself. Clearly, the new religion already comprised elements of spontaneous monotheism and became the foundation on which Moses later built his monotheistic faith. It is very difficult today to reconstruct the prototype of the faith that Abraham professed given that all events from this period were recorded only 1000 years later and were subsequently heavily edited by the compilers of the Pentateuch. Naturally, the biblical writers would have tried to impart to Abraham’s new religion a distinctly monotheistic character that would have been true of a much later period, thereby creating the appearance of complete continuity from Abraham to Moses.

The family tree of Hebrews and their relatives

The land to which Abraham led his group of tribes differed substantially from both Ur and Haran. Here there were no significant rivers like the Tigris and Euphrates, and there was not as much rain as in northwest Mesopotamia. Life in Canaan completely depended on the amount of rainfall. There were years when rainfall was almost non-existent and the whole country was thus seized by severe droughts, which in turn led to famine. The nearest place where there was always water in abundance was the Nile Delta in Egypt. And it was to the Nile Delta that the nomadic Amorites went when dry periods occurred in Canaan. W...