I.Introduction

In November 1622, Louis XIII planned a visit to the city of Marseille. His goal was to reaffirm the ties between Marseille and the Kingdom of France, and to dissuade the city from seeking political autonomy from the royal state.1 A fervent hunter and weapons master, Louis XIII allocated time in his busy schedule to fish tuna in the natural harbour of Morgiou, located in the south-east of Marseille. Since 1452, Morgiou had been the property of the fishers of Marseille, who elected their representatives, raised taxes and exercised their own jurisdiction over the disputes that invariably arose in their fishery. In other words, Morgiou was part of an enclave of private governance within the Kingdom of France.

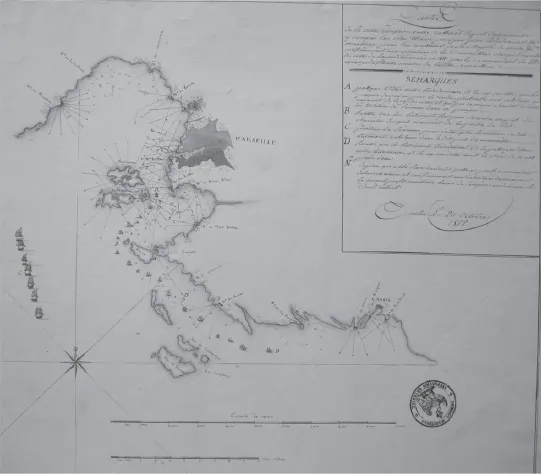

Figure 1.1 The Fishery of Marseille

Source: Archives nationales (France), Cartes et Plans, G212 no 51 (20 October 1812). Morgiou is located on the right side of the map, near Cassis.

The king’s visit was critical for the fishers of Marseille, who were hoping that Louis XIII would confirm the rights and privileges that they had accrued since the Middle Ages. According to legend, the fishers dug stairs into the stone of the cliffs surrounding Morgiou in order to enable Louis XIII to descend safely to the beach. Four hundred years later, curious visitors can still see remnants of these ‘stairs of Louis XIII’ in Morgiou.

The fishing party took place on 8 November 1622, in a special tuna trap called a ‘madrague’, a source of immense pride for the local fishers. The madrague was the latest fishing technique originating from Spain, which could catch up to 1,000 tuna and had just been installed in Morgiou. Archival documents report that Louis XIII killed more than 25 tuna with a golden trident and that he ‘had never seen anything that pleased him so much during his trip’.2 It was not long before Louis XIII expressed his satisfaction through concrete acts. On 30 November 1622, around three weeks after the fishing party, the king confirmed all of the rights and privileges that the fishers of Marseille enjoyed over a vast territory encompassing more than 20 miles of coastline.3 These rights included the opportunity to elect their own representatives in the Prud’homie de Pêche (or simply the Prud’homie), an organisation that exercised broad powers over the regulation of the fishery, its policing and the settlement of disputes among fishers.

Fast-forwarding 400 years to the present day, the Prud’homie still exists and is still endowed with similar powers. This, in itself, represents a remarkable story of private governance and institutional survival. The truth is, however, that it has survived in name alone: the Prud’homie rarely, if ever, uses any of the powers that it has accrued over the centuries. Today, it is an empty shell that fishers cherish as a symbol of their past glory. Morgiou also still exists: it remains the same amazingly beautiful harbour where Louis XIII fished for tuna in the seventeenth century. However, bluefin tuna have almost entirely disappeared from the area and Morgiou has been incorporated into a natural park, where fishing activities are strictly regulated. This book tells the story of the Prud’homie, a private order that had successfully operated for centuries before entering into decline. In other words, it is the story of the life and death of a system of private governance. Before telling this story, however, I will first present the theory of private governance and explain why the case of the Prud’homie matters in this context.

II.The Rise of Private Orders

Over the past few decades, an emerging stream of scholarship has developed a theory of so-called ‘private orders’ (also known as systems of ‘private governance’ or ‘private legal systems’). These private orders are usually defined as systems that promote long-term cooperation among individuals on the basis of social norms.

The emergence of this field of scholarship has not come as a surprise to sociologists, who have traditionally paid attention to the norms that are frequently emerging in human societies. One pillar of legal sociology is that state law does not exhaust the wide range of mechanisms regulating social life and that legal rules must consequently be read in conjunction with social norms. The fathers of sociology, Emile Durkheim and Max Weber, converge in their analysis of why legal relations cannot be studied independently from social norms.4 One of the first scholars to examine the relevance of social norms in the context of a sophisticated legal system was Stewart Macaulay, who identified the importance of non-contractual norms in the operation of businesses based in Wisconsin.5 Sally Falk Moore, for her part, aptly captured the complex interactions between social and legal norms using the term ‘semi-autonomous social field’.6 Through the study of ‘legal pluralism’, socio-legal studies have further analysed how different forms of normativity coexist and intermingle in society.7 The term ‘private ordering’ itself was used for the first time by a prominent socio-legal scholar, Marc Galanter, who noted the need to explore what he calls ‘indigenous law’, that is, a set of norms that develop outside of state law.8 However, socio-legal scholars (also called ‘law and society’ scholars) have not attempted to theorise an object with which they have always been very familiar. Efforts to provide a theoretical framework for the study of ‘private orders’ have instead originated from another branch of legal scholarship called ‘law and economics’.9 Unlike socio-legal scholars, scholars of law and economics traditionally paid little attention to the emergence of norms beyond the state, at least until a few academic pioneers elaborated an analytical framework for the study of these norms. I will retrace the efforts of law and economics scholars (among others) to analyse the mechanisms of private governance, before examining the building blocks upon which they have based their theory.

A.The Pioneers of Private Ordering: Two Main Strands of Scholarship

One of the first and most important pioneers of the theory of private ordering is Robert Ellickson. In his important book Order without Law, Ellickson offers a broad and enlightening analysis of the ways in which ranchers in Shasta County, California regulate the issues arising from cattle trespassing.10 His findings are at once straightforward and highly consequential: while lawyers usually consider legal rules to be the reference point for the settlement of disputes, Ellickson shows how Shasta County ranchers rely on social norms to resolve disputes arising from cattle trespassing. The key reason proposed by Ellickson is the following: because transaction costs are too high for ranchers to identify and rely on the law, they prefer instead to turn towards social norms of cooperation and reciprocity (what he calls the ‘live-and-let-live’ philosophy) in order to regulate their interactions. Based on this case study, Ellickson introduces what he calls a ‘hypothesis of welfare maximizing norms’, according to which ‘members of a close-knit group develop and maintain norms whose content serves to maximize the aggregate welfare that members obtain in their workaday affairs with one another’.11 In a separate article, Ellickson presents similar findings in relation to New England whalers, who relied on three main norms (‘Fast-fish, loose-fish’, ‘Iron-holds-the-whale’ and ‘Split ownership’) to regulate whaling in the nineteenth century.12 In another book, Ellickson observes yet again how ‘households’ can achieve ‘welfare maximization’ through social norms.13 Ellickson’s scholarship has come to represent a reference point for the literature on private governance. His plea for social norms has inspired numerous scholars and encouraged them to look more closely at the inner workings of societies when assessing the strength of legal mechanisms.

Another important study of private ordering has reached similar conclusions, on the basis of a study of diamond traders. In an important article, Lisa Bernstein analyses the organisation of the diamond trade in New York City.14 She argues that diamond traders rely on the mechanisms offered by their private club (the Diamond Dealers Club) to govern what she calls ‘extralegal’ contracts. These traders rarely, if ever, turn to the ‘official’ legal system when making contracts and settling their disputes. Bernstein identifies the taste for secrecy among diamond traders and the inadequacy of the damages awarded in the official legal system as key reasons for their preference for ‘extralegal’ contracts.15 Although her analysis is less focused on social norms than that of Ellickson, Bernstein notes that social norms must be ‘Pareto superior to the established legal regime’ in order to survive.16 In other words, both Ellickson and Bernstein seem to consider that social norms prevail over the existing legal system...