- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Colonel John Boyd, a maverick fighter pilot, revolutionized the American art of war but his research relied on accounts written by Wehrmacht veterans who fabricated historical evidence to cover up their participation in Nazi war crimes. The Blind Strategist separates fact from fantasy and exposes the myths of maneuver warfare through a detailed evidence-based investigation and is a must-read for anybody interested in American military history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Blind Strategist by Stephen Robinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

EMERGENCE OF MANEUVER WARFARE

ACTIVE DEFENSE

During the final years of the Vietnam War, the American military unraveled as discipline broke down and forty-five officers and NCOs were killed by their own men in ‘fragging’ incidents between 1969 and 1971.1 The institutional decline extended beyond the warzone as Donn Starry, who commanded the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment in Vietnam and spearheaded the invasion of Cambodia in 1970, recalled:

Forces that deployed to theaters other than Vietnam suffered mightily from personnel turbulence, the drug culture, multitudinous disciplinary infractions (the military jails were full to overcrowded), and depletion of the experienced NCO corps, all reflected in a serious lack of confidence in leadership at virtually every level.2

When final defeat came in 1975, the military suffered a traumatic shock as 58,318 Americans had died in a conflict ending with humiliating images of helicopters evacuating the embassy in Saigon. In the aftermath of Vietnam, the downward spiral continued as Roger Spiller from the Army’s Combat Studies Institute explained:

The indiscipline first appeared in Southeast Asia and was translated after the war to the European formations, manifesting itself in numerous racial incidents, drug and gang-related violence among soldiers. Some officers walked their night tours in the company areas with rounds chambered in their side-arms.3

At this time, the Army struggled with declining defense budgets and the challenge of transitioning to an all-volunteer force, creating the need for recruitment and retention at a time of extremely low morale and when public confidence in the military had collapsed and service lacked the social prestige it once had.

General William E. DePuy emerged out of this abyss and rebuilt the United States Army. He had served as a junior officer in World War II, fighting in the 90th Infantry Division in Normandy.4 The soldiers, mostly poorly trained draftees, endured massive casualties while fighting under abysmal leadership. Several officers were relieved of command, leaving DePuy with a burning belief in the importance of training and competent leadership: ‘I fought in Normandy with three battalion commanders who should have been relieved in peacetime. One was a coward, one was a small-time gangster from Chicago . . . and the other was a drunk.’ He added, ‘In the six weeks in Normandy prior to the breakout, the 90th Division lost 100 percent of its soldiers and 150 percent of its officers. . . That’s indelibly marked on my mind.’5 DePuy remembered the division as ‘a killing machine — of our own troops!’6

Later in Vietnam, DePuy commanded the 1st Infantry Division and focused on search-and-destroy operations, gaining a notorious reputation for sacking incompetent officers, resulting in the Army Chief questioning this practice as he recalled: ‘I either would have to be removed or I would continue to remove officers who I thought didn’t show much sign of learning their trade and, at the same time, were getting a lot of people killed. You can’t get a soldier back once he’s killed.’7

In 1973, DePuy became commander of Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), which had been recently created to centralize training and doctrine, but he viewed his role as ‘nothing less than to totally rethink the way the Army trained its forces and fought its wars’.8

William E. DePuy

(Author’s Collection)

(Author’s Collection)

After America withdrew combat forces from Vietnam, the Army refocused on its traditional Cold War role of defending Western Europe against a possible Soviet invasion. Red Army forces in Central Europe had significantly modernized, resulting in more and better equipped soldiers being stationed along the borders of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries. In 1976, NATO had 6,655 tanks and 800,000 soldiers while the Warsaw Pact fielded 15,450 tanks and 925,000 soldiers.9 The Red Army also had qualitative superiority as their BMP-1 infantry fighting vehicles, T-64 and T-72 tanks, and Mi-24 Hind attack helicopters outclassed obsolete American equipment such as Sheridan armored vehicles and Patton tanks. However, DePuy’s response to NATO’s defense challenge originated from the Middle East.

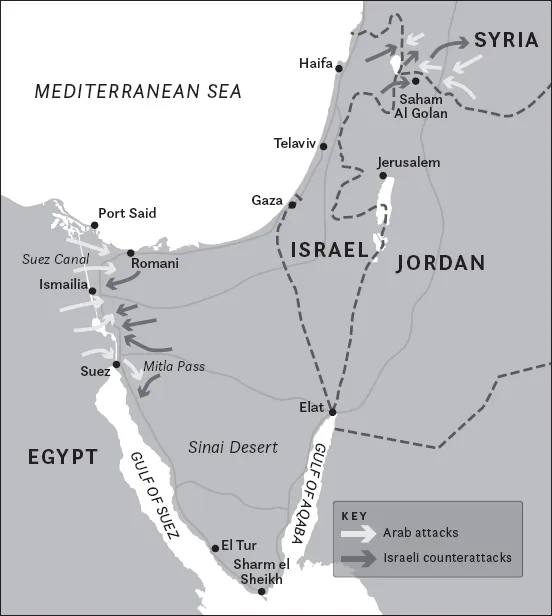

DePuy viewed the Arab–Israeli Yom Kippur War of 1973 as an opportunity to gain battle-tested insights into combat between modern American and Soviet weapons. TRADOC accordingly compared the performance of American weapons against Soviet arms, interpreting Yom Kippur as a micro-version of a possible US–Soviet war in Europe. This conflict witnessed the most intense armored battles since World War II and modern technology enabled tanks to engage targets at 4,000 meters and infantry effectively operated precision-guided anti-tank missiles. During World War II, a medium tank firing at a stationary target 1,500 meters away would likely fire over twenty rounds before scoring a hit while a main battle tank would now in probability only need a single round.10

The Yom Kippur War, October 1973

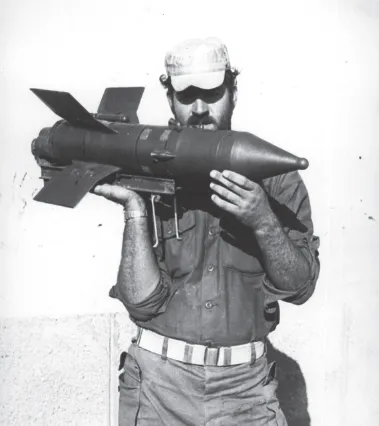

An Israeli soldier holds a Soviet-made ‘Sagger’ anti-tank missile captured during the Yom Kippur War

(Contributor: Keystone Press/Alamy Stock Photo)

(Contributor: Keystone Press/Alamy Stock Photo)

A destroyed tank from the Yom Kippur War

(Contributor: Universal Images Group North America LLC/DeAgostini/Alamy Stock Photo)

(Contributor: Universal Images Group North America LLC/DeAgostini/Alamy Stock Photo)

During Yom Kippur, over 400 Israeli tanks and 100 aircraft were destroyed while Arab forces lost 2,000 tanks and 400 aircraft.11 Israeli and Arab forces both suffered 50 percent material losses in less than two weeks of fighting, and their tank and artillery losses combined exceeded American equipment levels in Europe.

To DePuy, Yom Kippur demonstrated the sheer destructiveness of modern battlefields due to technology which heralded a ‘new lethality’ or, as he put it, ‘what we see we can hit; what we hit we can kill’.12 However, he also observed the importance of training and leadership in the ultimate Israeli victory, as computer simulations predicted that the Israelis should have lost every battle.13 DePuy remarked that ‘training and leadership weighed more heavily than weapons systems capabilities on the actual battlefield’.14 He concluded that contemporary conventional wars would be short but intense limited conflicts as ‘modern weapons are so lethal that the outcome of the next war will be largely settled in weeks with the forces and weapons on hand at the outset’.15

DePuy decided to reform the Army based on his observations of Yom Kippur by rewriting Field Manual (FM) 100-5 Operations, initiating a ‘program to reorient and restructure the whole body of Army doctrine from top to bottom’.16 Doctrine shapes military culture, values and behavior, and DePuy perceived it as the ‘unifying concept’ which coordinates operations, training, education and leadership by articulating ‘How to Fight’.17

FM 100-5 Operations is the Army’s capstone doctrine at the top of the hierarchy and provides authoritative context and guidance for all subordinate doctrine manuals. This manual defines the Army’s warfighting philosophy, as Roger Spiller explained: ‘change 100-5 and one changes, ultimately, the way in which the Army fights’.18 DePuy articulated his grand ambition on 10 October 1974:

We have now participated in enough discussions, listened to enough briefings and seen enough demonstrations to have the best consensus on how to fight that has probably ever existed in the school system of the United States Army. It is now time to institutionalize and perpetuate this consensus through doctrinal publications.19

DePuy handpicked trusted loyalists to draft the new manual and General Donn Starry, who after Vietnam commanded V Corps in West Germany and was now commandant of the Armor School, became his principal collaborator. Starry shared DePuy’s interpretation of Yom Kippur and the ‘new lethality’ as battlefields would be ‘dense with large numbers of weapons systems whose lethality at extended ranges would surpass previous experience’.20

Starry genuinely believed in DePuy’s doctrine reforms but warned about the need to gain consensus by involving the rest of the Army in open debate; however, DePuy had little interest in exposing his ideas to criticism.21 He only tolerated minimal consultation with the rest of the Army and wrote much of the new manual himself with the help of his small team, dubbed the ‘boat house gang’ as it met in a building which had once been a yacht club. DePuy did, however, seek advice from General Bruce Clarke, who commanded an outnumbered force from the 7th Armored Division which opposed the panzer onslaught at St. Vith during the Battle of the Bulge. DePuy perceived this battle as an historical parallel to NATO’s current position.

DePuy’s efforts resulted in Active Defense, a new warfighting philosophy expressed in FM 100-5 Operations (1976), which planned to defeat a Warsaw Pact invasion of Western Europe close to the West German border. Given the ‘new lethality’ of modern weapons, the conflict would likely end before America could mobilize; therefore, troops already in Germany must defeat the invasion.22 The outnumbered NATO troops would adopt an elastic defense and use firepower to destroy the initial Soviet assault.23 NATO forces would initially conduct a series of defensive engagements from prepared positions and, after the Warsaw Pact’s main effort was identified, they would concentrate mass force to counter the main blow. Active Defense viewed operations being tightly controlled by generals with limited independent action being tolerated down the chain of command, as DePuy insisted on ‘the need for commanders to maintain near absolute control over subordinate units on the battlefield’.24

Active Defense centered on NATO defeating Warsaw Pact forces during the ‘first battle’ because the ‘new lethality’ would result in domestic and international pressure, forcing politicians on both sides to end the conflict before a ‘second battle’ could be fought.25

Active Defense, as DePuy announced, took ‘the Army out of the rice paddies of Vietnam and places it on the Western European battlefield’.26 He confidently told his staff that its ‘impact will be a thousand fold. It will be more significant than anyone imagines’ and ‘will show up for decades’.27 However, Active Defense drew immediate criticism from a new generation of American reformers, believers in a radically different warfighting philosophy.

THE REVOLT

DePuy discouraged criticism during the drafting of FM 100-5 Operations (1976) but he could not control the debate which followed its publication, and intense criticism soon came from a most unexpected individual, William S. Lind, a civilian defense analyst and legislative aide for Senator Robert Taft, Jr. Lind had graduated from Princeton with a Master’s degree in German history and had an active fascination with the country’s military past.

On 11 February 1976, Lind m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Content

- Introduction

- 1 Emergence of Maneuver Warfare

- 2 The Maneuver Warfare Revolution

- 3 History Written by the Vanquished

- 4 The Father of Blitzkrieg

- 5 Wehrmacht Operations: Myth and Reality

- 6 Riddle of the Stormtroopers

- 7 Maneuver Warfare and Operational Art

- 8 Maneuver Warfare and the Defense of NATO

- 9 The Gulf War and the Illusion of Confirmation

- 10 The War on Terror and the Return of Attrition

- 11 Fourth Generation Warfare and Educating the Enemy

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright