![]()

1

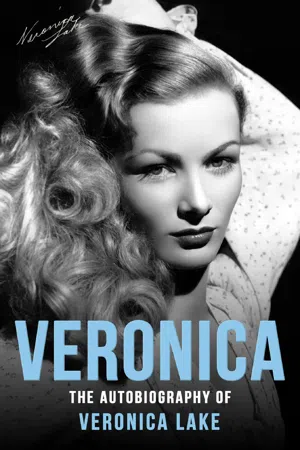

Veronica Lake is a Hollywood creation. Hollywood is good at doing that sort of thing. Its proficiency at transforming little Connie Ockleman of Brooklyn into sultry, sensuous Veronica Lake was proved by the success of the venture. And the subject, me, was willing and in some small ways able.

I don’t mean to imply that Veronica Lake is pure past tense. I still sign my checks Veronica Lake. My telephone is listed under that name. And, in general, I am still Veronica Lake.

But it would be spurious to write this book from Veronica’s point of view. Constance Ockleman has been the veracious liver of the life, and she’s the proper person to tell the story.

l was sixteen when I first saw Hollywood. My first stepfather, mother, cousin Helen and I made the automobile trip from Florida in the summer of 1938. The car was a Chrysler Airflow and I remember the all night drive across the final stretch of desert and crossing the California state line early the next morning. It was the Fourth of July, a significant date in American history and certainly in my life.

Hollywood had, quite naturally, captured my imagination as it had that of most other young girls. It had exerted its powerful and mysterious magnetism in darkened theatres where shadowy images flickered on large screens and dashing gentlemen spoke to frail, beautiful women, their words in surprising syncopation with their lips. Romance prevailed at all times. I’d sit there, popcorn, purchased with money saved by walking instead of riding clutched tightly on my lap, and be swept away, far away with whatever particular hero happened to reign that Saturday. What splendor fifty cents could buy. What virile men and what fortunate women to be with those men.

Of course, it isn’t that way today, with shared knowledge that the leading male box office idol is really homosexual, and the top siren of the screen is asexual and smokes pot—alone.

But Hollywood promised something to everyone. As with aviation, 1938 pointed to bigger and better things; jets to replace Ford Tri-Motors and new stars to replace old. And where did new stars come from? Heaven, maybe, or some place equally as vague.

And there I was in 1938. I was in Hollywood. And strangely enough, it didn’t seem any different from any other place I’d seen. We drove through streets, each looking out his or her window for movie stars or gold pavements or anything to fulfill the promise. And it looked the same as Florida, or Brooklyn, or even Saranac or Placid in summer, with only minor variations not worth mentioning.

Why the hell I expected it to look any different is something else again. I find myself being drawn into a shell of feigned sophistication as I think of my autobiography. How nice to present a devil-may-care attitude when reaching back into your own private past, a past with no one really to refute what you say about your inner feelings. It’s a strong temptation to lie, or at least embellish, which is probably why any autobiography is usually less true than biographies written by the impartial bystander.

But I won’t succumb at this early stage to such an impulse. Veronica Lake might. Not Constance Ockleman.

I certainly wasn’t blasé when I saw my first real live star. We’d driven around for over an hour when hunger dictated the next move. We found a drive-in restaurant, pulled in and happily ordered hamburgers and Cokes. We’d almost finished eating when another car pulled in alongside ours. I looked over and there behind the wheel sat Ann Shirley. I over-reacted, of course. What would you expect of a fifteen-year-old girl?

“There’s Ann Shirley,” I babbled.

“Where?” My mother also over-reacted, which was not at all unusual. I didn’t realize it fully then, but there was little doubt my mother was banking on a film career for her only child. Maybe Ann Shirley could help things along.

“Next to us.” I’d fallen into a whisper for fear she’d overhear.

“Why don’t you go over and say hello, Connie?” my mother suggested with a smile to breed confidence.

“Oh no, Mommy.” She insisted I call her Mommy.

I couldn’t. I just sat there gaping through the window, turning away now and then to avoid being caught. I was actually relieved Miss Shirley finished her hamburger, the same kind we enjoyed, paid the girl the same amount of money it would cost us, and drove away. I sighed a long sigh of satisfaction at having seen a movie star.

My mother’s sigh was equally as long, but indicated a different emotion.

At that point I was ready to head back home to friends and familiar surroundings. The trip, now that I’d seen a Hollywood personality, was over for me. There didn’t seem any sense in staying longer.

But Hollywood was home now. Our new home. And it was to be my home until 1952.

We moved into a small rented bungalow on Oakhurst Drive, Beverly. It wasn’t twenty-four hours before I’d forgotten about being in Hollywood and about movie stars and other star-spangled dreams. It was just a matter of settling into a new neighborhood, searching out new friends, finding one’s way after losing the security of ways already explored and charted.

Thank goodness for Helen Nelson, my cousin. We were more chums than blood relations, and we soon set out to establish rapport with Los Angeles. It was easier together, as is usually the case. We did sixteen-year-old things, ordinary things, and found sixteen-year-old enjoyment from them. There wasn’t the smog then, and we’d walk along together in the warm California sun enjoying whistles and comments from drugstore cowboys and new street names and giggle-giggle at almost everything. I had a full figure at sixteen, with surprisingly full breasts, a fact that many people assume was never the case with me. Why people think short girls must also be flat-chested is beyond me. I jutted out in front pretty good and was aware enough at that age to be able to walk certain ways to give me some jiggle and jounce. I knew the boys enjoyed that sort of thing, and I enjoyed their enjoyment.

Sometimes, when we wanted to discourage a boy from continuing his awkward advances, we’d set him up a little by encouraging him along. Then I’d say something to Helen like, “Have you ever heard anything so childish?” Or, “How do you like that?” with emphatic rising inflection at the end.

Adapting to the new situation really didn’t prove as trying an experience as it might have been. Change had been a fairly constant part of my life.

I was born in Brooklyn, spent my pre-school years in Florida, my grade-school years in Brooklyn, and my high school years in Florida and Montreal. No, my roots weren’t as deep as they might have been under other family circumstances. I’d even taken on a new name. Constance Ockleman became Constance Keane with my father’s death in February 1932, and my mother’s remarriage a year later to Anthony Keane, a staff artist with the New York Herald Tribune. I liked my stepfather, although I didn’t know him very well and he in no way served to replace my real father. Little girls like their daddy, and I adored mine. But Anthony Keane was nice, an outgoing man with certain warmth and the ability to make you feel comfortable when he was with you. My mother knew him before my father died, and I suppose loved him, at least enough to marry him.

I’m quite certain in retrospect that part of my ready acceptance of this new father was the fact he wasn’t a well man. His frailty brought me closer to him. I’d always been attracted to the sick or unattractive, and still am. I don’t mean to have you presume me a patron saint of the unfortunate. Far from it. In many cases people drawn to less fortunate people are somewhat perverted, or, at best, are playing out and satisfying certain self-serving interests and needs. It’s good these people exist, no matter what the motivation. They do help their fellow men, and you can’t fault that. I’m not looking for faults in my own make-up, either. I’ve got enough without looking for them. It just seems honest to admit to the possibility of less than philanthropic inducement for my actions.

I spent most of my first year in Hollywood killing time. Sure, I thought of becoming an actress from time to time. But it was daydreamed in passing; there was no compulsion, no inner drive that lent urgency to the notion. It was still little-girl romanticizing without basis or, most important, without a potential resolution of the dream. I’d talk big sometimes but it was just talk. Like when I announced to Helen as we passed Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, “Someday my hand print will be there,” pointing at the famous cement. I was asked to join the concrete hands of Grauman’s after I became a star and turned it down. No special reason. I just didn’t feel like it.

I was enrolled by my mother at the Bliss Hayden School of Acting on Wilshire Boulevard. I’d met some girls who were working as extras in films and again, without the proverbial stars in my eyes, entered the school because it was something to do.

(I apologize here for taking time to again stress my attitudes towards a career in motion pictures. So many girls enter acting classes convinced they will become stars. They must become stars and seldom do. I began lessons convinced I would not become a movie star. Or, to soften my vehemence, quite sure it could not happen until I was at least fifty years old.)

Studying at the Bliss Hayden School was fun, although hardly stimulating. We would put together scenes from various plays, each with a broad range of parts that would not prove too discouraging for us. There was no sense in losing paying pupils.

I remember starring in many of these intra-squad productions and giving my all with such lines as:

“Good morning, mothaaaaaa.”

“Dinaaaaaa is served.”

Or even,

“Tennis anyone?????”

We also indulged in the inevitable exercises of walking into a room with a heavy book balanced precariously on your head, walking down steps with chin held high, and talking in time with a metronome, the latter a funny feat but one I’ve always been suspicious of in terms of furthering an acting career.

But it was all enjoyable, and since that’s the only reason I ever showed up at all, I can’t complain.

I did make a lot of friends at Bliss Hayden, many of them girls working around town as extras. And one of them, Gwen Horn, was directly responsible for my ever appearing in a film in the first place.

Gwen had been notified of a casting call for Sorority House, a feature with James Ellison, Barbara Read, Adele Pearce and none other than Ann Shirley.

It would be flattering to Gwen and very showbiz to say she convinced me to answer the call with her because she’d seen some hidden acting ability gone unnoticed by the Bliss Hayden instructors. But that isn’t the way it happened.

“Connie, I’ve got to make this call at RKO for Sorority House. Come on with me and keep me company.”

“Sure Gwen, I’d be happy to.”

That’s what happened. I went with Gwen and they gave both of us parts.

You don’t have to act very much to be an extra in films. Casting directors choose extras simply because they look like the kind of people you’d expect to see in a given scene. In fact, directors will occasionally get damned mad at an extra who does act, and is caught at it. In a way, extras are supposed to be the only real people in a movie. It’s just plain old you there on the screen, not trying to emote in any way but just there on the street while the good guy kills the bad guy, or there in the audience as the singer sings his heart out in lip sync.

I stood completely in awe of John Farrow, the film’s director. He was not only a fine director but was a fine man. He’d been knighted by the Catholic Church for writing Father Damien and the Leper. You remember the Father Damien story, don’t you? He was the Belgian missionary to the lepers of Molokai.

Well, John Farrow was obviously a very good Catholic. And it impressed me. I was a Catholic also, but one of the growing number who even then began a gradual slide away from the church’s dogma. I’d already begun my religious decline, but you don’t easily shake the Roman Catholic Church. I was sufficiently saturated still to respond automatically to a “good Catholic,” and John Farrow fell into that category.

I was also impressed with Ann Shirley. I wanted so much to tell her about the drive-in but never really found the nerve.

I did talk to her on my last day of shooting.

“I never thought I’d be in a film with you, Miss Shirley,” I told her, or something equally insipid.

“I hope you’re in many more,” she answered.

I doubted if I would be. But the thought did have its appeal. I was learning more just standing around watching the professionals work than I’d learned in all the academic exercises at Bliss Hayden. But that’s usual in any field, and I cannot refute the benefits I received from classroom training. Mr. Hayden himself was very encouraging to all the students, and he did help me build some smattering of confidence.

I’ve thought many times how nice it would have been to have enjoyed more formal training. Schooling of any kind enables you to become so sure of the basic skills and tools of your trade that you don’t have to waste precious energy thinking about them. You’re free to use them naturally in developing whatever it is you’re doing. Fortunately, I was blessed with some unexplainable intuition about performing. That isn’t an egotistical statement. It doesn’t mean I was born a gifted actress. There were occasional critics who thought I was slightly gifted, at least in those specific roles they reviewed. Bless those few.

But I did have a certain natural feel at times for what to do in a given situation. And having that went a long way in making up deficiencies in academic training.

I also talked with John Farrow during that day. The scenes in which I appeared were completed, and I drew a deep breath before approaching him. Actually, I was about to indulge in a sophomoric stunt to indicate to him my esteem for his religious strength.

I’d decided to wait until my involvement in the film was completely finished. I didn’t want to do anything that might be constructed as currying favor with the director. The last thing I wanted was to be known as a young, ass-kissing extra looking for bigger and better parts. That’s a pretty silly attitude when you think about it. It was totally accepted for a young girl to offer herself to anyone of importance in return for a break in films. My little token offering was straight out of Snow White.

My gift to John Farrow was, in fact, a gift to me from an aunt on the Keane side who was a nun. She was constantly sending me religious articles that had been blessed by the Pope. Whether she did this believing me to have deep love for the church, or because she was given divine inspiration into my falling from grace, is unknown to me to this day. The important thing is she did send me these gifts quite regularly. And as disillusioned as I was with things religious, I wasn’t sure enough to come out with a final condemnation. I suppose I was trying to copper my chances with heaven and hell, a cowardly approach but practical, you’ll admit.

“Mr. Farrow,” I said with as much spunk as I could muster at the time, “I’m Catholic, too . . . like you . . . and I’d like you to have this, if you don’t mind.”

He was surprised. I think he wanted to laugh, or didn’t want to but couldn’t help himself. Maybe it was the southern accent in...