![]()

Chapter 1

How not to partner with startups

“Don’t let it end like this. Tell them I said something.”

— last words of Pancho Villa (1877–1923), according to legend

This book is written, in large part, to settle a misunderstanding. Tech startups are so alluring these days that everybody thinks they should be a founder, that they need to obsess about startups, and live and breathe technology. Far from it; in truth, many of us would be better off simply adapting the tech innovator’s mindset and building an organizational repertoire that mimics, courts, and most importantly, deeply understands founders and everything that they do, including their frequent failures.

The good news is, this is very doable. As the evidence collected through interacting with thousands of founders, academics, policy makers, and executives will show, the tech entrepreneur’s mindset includes seven key behaviors that anyone can master: being focused, relentless, decisive, reliable, direct, vulnerable, and adaptive. Why is it so rare? Perhaps because we are not talking about teaching this to individuals but teaching them to teams and organizations as a whole. You don’t need a degree in sociology to know that the complexity grows more than n+1 with each new individual added to the mix. But exactly how does that work? And, what about other factors, such as technologies? Innovation is sociotechnical in nature, and requires full awareness of how social and technical aspects interact.

In fact, these innovation attributes are more than traits, behaviors, or “muscles” you can train in isolation. What you need to do, as an innovation leader, is to develop life habits and hone them, and inspire others to practice them. Over time, these “instincts” become commonplace, and you set yourself up for gleaning the kind of everyday insight and social sensitivity needed to detect and utilize possibilities in tech and apply them to your own life, work, and projects. Don’t just train your body; train your mind. Practice behavior that just might lead to innovation. Be in the places where innovation occurs.

Top MIT faculty who find themselves as serial founders of tech companies exhibit these traits but exercise a restraint: they typically let their students or experienced CEOs run with their companies and continue to innovate exactly as before. Nobody thinks any less of them.

Silence is bad for corporate–startup collaboration

There was no easy way to say it. Despite everyone’s best efforts, the startup venture’s efforts to get a trial contract with the large multinational corporation had failed. At least, that was going to be my message to them. We had tried everything. As the lead of the MIT Startup Exchange program, I had introduced them and then reintroduced them to the innovation scout. Andy, the founder, had then met with them. He had introduced them to several corporate business units. There had been several follow-up calls and emails, even two corporate visits with extensive demos and long dinners. Then, silence. Not the kind of silence that happens before a big transaction, but complete silence, the kind of absence of communication that only characterizes the worst of marriages gone wrong. The kind that means someone is actively ignoring you. This had gone on for months. In fact, it was approaching the year mark. I was about to call it.

Then, as I was about to conduct the postmortem together with Andy, the startup’s enthusiastic founder, over an unusually good office espresso (thank you Nescafé), an email ticks in, and soon he gets a phone call. It is the corporate innovation scout. He wants the founder on a plane across the world—tomorrow—for a meeting with the CTO. They are contemplating making the startup their preferred partner for artificial intelligence. The deal is consummated within weeks.

With Regina, founder of another MIT startup with a similar product, the story had been different. I had set up the meeting. The large financial services company had met her for an initial 20 minutes, and she had done the typical startup pitch (e.g., point out the customer pain): “Dear old-fashioned prospective customer in the slow-moving financial services sector, here is my clever fintech solution that will save you a lot of headache and will put you ahead of your competitors.” The meeting had stretched to 45 minutes, upon which the Head of Innovation stormed out of the meeting to make a call. I briefly overheard phrases I later understood the meaning of: “Just plan a trip right away.” He had decided to start a pilot collaboration right then and there after only one face-to-face meeting. Was this company outstanding? Perhaps so, but not more outstanding than the one previously mentioned. Were the circumstances different? Yes, they were, because in this case the decision maker was in the meeting. But that does not explain everything. There was also something about the trust between me as the matchmaker and the innovation executive. But there were also other differences that matter. We will unbundle all these kinds of expectations later. Let’s look at a third example, again from MIT’s corridors.

Clark, the innovation scout from the massive aerospace company I was helping to connect to MIT innovation, came over to me at a reception and suddenly said to tell my startups not to sell so much, have them stop pitching, the sale is already done. He was slightly annoyed that one of our startups had proceeded to present their entire slide deck of 30 slides to one of the EVPs in a strategic business unit even though, in Clark’s mind, the decision was already made. “Trond,” he had said, “you made the intro and said this was one of the top companies spun out of MIT with the type of manufacturing technology we have requested. Why is your startup still pitching? For us, the only decision from there would be, how should we structure the project?” I was thrilled. Innovation flow was at play.

![]()

| KEY TAKEAWAYS & REFLECTIONS |

- Learn from founders, but don’t envy their startup life unless you truly want it. Ask yourself: Are you ready for a startup?

- Embrace the tech entrepreneur’s mindset; be focused, relentless, decisive, reliable, direct, vulnerable, and adaptive. Over time, they will become habits. Reflect on the following: Which of these traits are more difficult for you?

- Don’t play bait and switch with startups. If you partner with them, accept that they are different. Think back—have you always been forthright when you worked with a startup?

- Rethink open innovation. Seeking input is great, but make sure you truly want it, can act on it, and make sure to look for the right type of input. Open innovation is not a detailed specification; it is an invitation to grow and change. What opportunities have you had to engage in open innovation? What did you learn?

- Be skeptical if large companies claim they are highly innovative. They might be just the opposite. If you see somebody whose title is Innovation Director or higher, run for your life. That means senior leads admit there is not enough innovation present. Is there such a per-son in your organization? Is it you? When did this position get created? What did it lead to?

- Reflect on what it means that a true innovator is, in equal parts, changemaker, tech guru, and business person. What would that mean for you? Where is your strength? Which aspects do you need to work on? What’s your plan to do so?

|

![]()

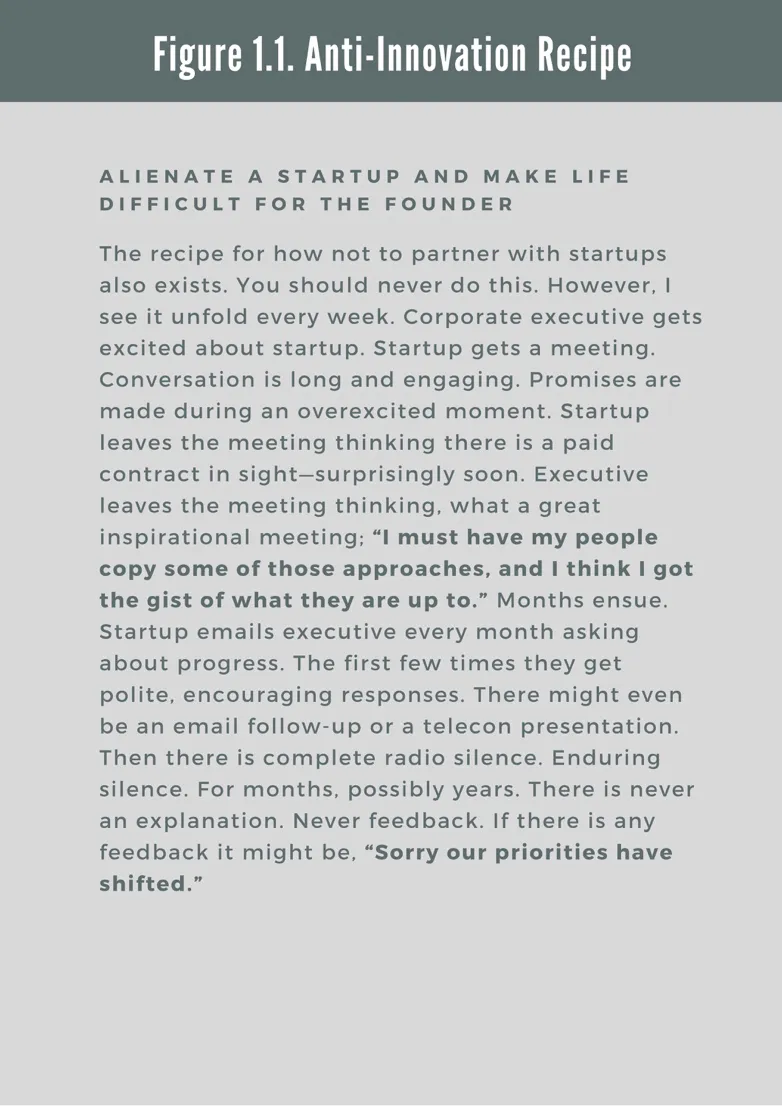

Why should an executive never play bait and switch with a startup? Because rumor spreads that there is no follow-up. Such behavior contaminates public reports of that company being innovative. It is also bad manners and it is unhelpful.

Legal rigidity hampers innovation

Failure mode number two in the early stages is that a corporation sends the startup a legal document—either a contract document, a procurement process file, or something of this sort, perhaps an overly onerous nondisclosure agreement—and expects the startup to sign or no deal, with no negotiation. There might be a clause that the company only buys from companies that have been in business minimum 10 years and have over 1 million in annual revenues. There may be something about the startup needing to have insurance. Well, startups do not have insurance, not until they absolutely need it. In one of my startups, I remember buying insurance because having insurance was a required clause I had to sign in a client contract.

One of my startups partnered with such a Fortune 500 corporation once. We even signed a contract with them. That contract was signed making some allowances for us being a startup. But then the company started treating us like a corporation again. First, there was the notion that the onus was on us to check and double-check things that could not possibly have been high on our awareness list, things like what type of subcontractors the corporation was allowed to use, given they operate in a regulated industry. In the end, they accused us of poor background checks on our subcontracted experts despite the fact that their own representative had gone through the expert choices and had enthusiastically agreed that these experts were the right way forward. A corporation always covers its tracks. Startups beware.

These stories are not unique. In fact, they happen every day. More than half of the attempts to collaborate still fail due to a clash of mindsets between passionate, entrepreneurial startups and more process-oriented and risk-averse corporates. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), “failure to appreciate each other’s mindsets, incentives and concerns can lead to failure to realize the potential for win-win collaborations,” and further, “corporates need to avoid seeing start-ups as innovation units or sources of free consultancy: entrepreneurs resent corporate ‘start-up safaris’ that distract them from their core activities.”2

Only the bottom of the barrel, both among corporates and startups, experience safaris these days. They both have learned to avoid them like the pest. The majority of players with operations in US innovation hubs (Silicon Valley, New York, or Boston) have long since crossed that abyss, although some still have this challenge when their domestic C-levels visit their own innovation outposts.

How to achieve great corporate–startup interaction

The way the corporate–startup interaction is set up and the quality of the interaction between the two parties depend on a multitude of factors that we will explore in this book, from organizational to individual to structural. Some digital platforms are better suited to one type of interaction over another. Getting the right mix of activities is what matters the most. Any oversimplification and quick guiding principles are likely to miss the target.

Corporate innovation, a bit of a misnomer, is full of perplexities. Most of the companies that are recognized in the media for being innovative—in fact, most companies with innovation awards proudly displayed as part of their promotional materials—have very shabby innovation track records in terms of day-to-day innovation practices. I have seen this play out many times, even among the Fortune 500 brands that we all know. Instituting a certain innovation procedure that looks good on paper does not mean it is good in practice or that it is followed. Corporations may, in fact, have tremendously elaborate innovation frameworks in place. They may even have a process for insourcing innovation from startups. Possibly, they could be avid sponsors of startup competitions through third parties or even host their own startup competitions. Or, they have their own accelerator program with dozens of startups hosted in their own corporate facilities. Yet, they quite possibly could still be toxic for startups.

Little of that matters. At the end of the day, what matters is whether they walk the talk, day by day, decision by decision, person by person. Every company can have a process for innovation (although many do not). Every company can hire an innovation scout (most big companies do). Every company can claim they have a strong innovation culture, proven by a track record of patents, product innovations, or impressive R&D budgets (what corporation does not?). True, investing in innovation matters. However, the deciding factor in whether a company is truly innovative is whether they are capable of completely ignoring their own rules of engagement when it matters most (they should be able to). Why? Because startup innovation seldom follows preestablished rules about when, how, and how much. You could have a principle of only engaging with Series B and C startups, yet if a seed-stage startup comes along with the right technology or product you either miss the boat or you engage then and there. Timing is everything when it comes to insourcing or outsourcing innovation. Six months later, the startup may be acquired by a competitor, may be preparing to go public, or may have gone bust. You simply cannot know.

The astounding thing in all this, perhaps the most perplexing phenomenon in all my time working with startups, is the absolute certainty and casual nature in which some angel investors (perhaps most annoyingly), venture capitalists (sadly), and corporate strategists (to their own detriment), either dismiss or praise a startup’s innovations with utter confidence.

Conversely, it is equally surprising and often unwanted when unfounded praise suddenly leads to impulse investments or strategic deals that have no realistic basis. The tech innovator’s mindset entails using improvisational skills, patience, street savvy, and an innate desire to fix a problem they see in their surroundings, to change the status quo for the better. To them, these corporate behaviors are normal, even expected, since they happen with such regularity, but that does not mean that they should be condoned.

The tech innovator’s mindset

Rules are detrimental to innovation, but what does matter is people and places. The interplay between the psychological makeup of the innovator and the organizational and physical setting within which this person inadvertently finds him- or herself matters even more. Would Andy’s many meetings have turned successful earlier had he approached them differently? How long will Clark’s enthusiasm last? Will he have time to see the successes and failures before he commits again? Will Regina’s pitch change now that this one was successful? As much as we are tempted to draw lessons, and always do, business, technology, and innovation is messy, fuzzy, and cannot fit into a standard template. What then?

In the following chapters, I will take you on a journey that defies the simple schemata that you usually find in business and innovation books. In the process, I am sure we w...